The Palestinian refugees of Fadel’s Island [located in Abu Kabir, al-Sharqiyya governorate]

During the Nakba in 1948, [Palestinian] refugees turned to neighboring countries as a temporary solution, waiting for the ceasefire. They left their stoves on hoping the war would end by the time food is ready. – Mourid Barghouthi, I Saw Ramallah (1997)

Forty of Beersheba’s residents fled Palestine on October 21, 1948 when an Israeli offensive began in their hometown. They carried nothing but water for themselves and their camels, and started their 10-day journey to Egypt. “We arrived in Aga, al-Mansoura, and then we found our way to Abu Kabir,’’ Nafla Hassouna, 102, said.

Beersheba is one of the largest and most ancient Palestinian cities. Called the Negev’s capital, it spans 84 square kilometers, located 71 km south-west Jerusalem. Its strategic location has always been the focus of fighting armies. The Egyptian Army was keen on securing Beersheba during the Battle of Beersheba in 1948 in order to control the Negev desert. Beersheba’s original residents were Bedouins who were well-known for raising camels.

‘’When we came to Egypt, we were greeted with food and milk. We settled in what was then a complete desert. We used mud and straws to build our new houses, and only then we felt safe,’’ Ghafra, another Nakba victim, said.

Sixty-seven years later, not much has changed. The houses are still made of mud or red bricks; there is no infrastructure, education or medical care. The place has grown into an isolated island surrounded by a belt of agricultural fields. This fort separates Fadel’s Island residents from the external world.

The island’s entrance is similar to solving a four-minute-puzzle; it requires a lot of turning and memorizing. On your way there, walking or riding a local Tuk Tuk in the two-car road, you can see bottom-naked children sitting idle by the sides, covered in houseflies, staring at anything colorful that is passing by. For a moment it may seem surreal, but unfortunately, it’s a harsh reality.

The island now hosts 3000 residents of 400 families that originate from one tribe, Abu Hussoun, al-Namooly clan. Seventy-five percent of the island’s residents are children. Families found relief in having as many kids as they could. “In our children, we find the homes we lost, the country we grieve, and the future we seek,’’ Om Fadel, mother of ten, said.

An average family consists of seven members. Numbers can grow up to 20. Abu Yassir, member of the island’s seven-member consultation committee, is married to two wives and has 17 kids and 60 grandchildren.

I mistook a pillow for my son

Nafla, who was 35 when she left Palestine for the last time, said there was no time to pack luggage; she fled with her brothers and her son as fast as possible. Halfway to Egypt, she turned to her newborn son, Ali, to breastfeed him, only to discover she had been hugging a pillow all along. ‘’My father, uncle, and grandfather had all went back to get Ali but they never returned,’’ she said.

The 102-year-old regards her life as a nearly ending journey with no remorse. She describes Gamal Abdel Nasser’s era to be its peak. *[under former President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s rule, Palestinians were treated as Egyptians, and Nasser refused external assistance to Palestinian refugees in Egypt.]*

‘’We were treated in the nicest manner, but everything stopped after a short while. I don’t know who’s in charge of Egypt anymore, but it would be nice if some heads turned to us for a while,’’ she added.

Nafla has 10 living children. She came to Egypt wearing a traditional necklace made out of Palestinian coins. She still wears it sometimes.

Ghafra, 76, has a vivid memory of the Palestine she grew up in. ‘’Palestine was heaven. Watermelons would grow on raindrops. We would harvest olives and prepare olive oil from scratch,’’ she said.

But when the war started, Palestine turned terrifying. Thirteen-year-old Ghafra couldn’t handle people killing each other over a piece of land. Ghafra’s life was mostly bitter. Her eldest son, Mansour, left for Iraq 37 years ago and she hasn’t heard from him since. Twelve years later, her daughter, Ahlam, was run over by a car in Abu Kabir when Ahlam was just 13 years old.

Ghafra’s current living conditions are miserable. While she sits and contemplates about her younger and healthier years, her daughter-in-law harvests crops all day to secure the family’s bread. Carts of geese and ducks fill her mud-based house, and houseflies eat up the humble furniture. Her house isn’t for the weak-hearted to enter.

Shamma, mother of Abu Yassir, arrived to the island when she was 12, and Abu Yassir was born 10 years later. Shamma is a firm believer in fate and considers coming to Egypt her luckiest experience.

My name is Maladan

Referring to mal-education: I asked 10-year-old Ramadan to pronounce his name he replied proudly ‘’Maladan.’’

It is utterly normal to see children playing with garbage piles, suffocating each other with plastic bags, hitting, fighting and crying. No one’s watching them. All the parents are out working either in agricultural fields or in recycling plastic.

Although the percentage of children is high, only less than 10 percent are enrolled in school. The number of dropouts is as high as ever. The enrolment procedures make it tough for parents to choose to educate their kids.

The nearest primary and elementary school is one kilometer away, while the secondary is 10 km far. Parents force children to drop out of schools so that they could work and help support their families, said Om Fadel, the mayor’s wife.

The papers required are the following: An acceptance from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a nomination letter from the governor of the Gaza Strip, social research stating the students’ financial statuses and, thus, their incapability to enroll in a private school, along with stating the distance between the students’ houses and the school (usually from three to five km). Then the papers are submitted to the Ministry of Education and the National Security Sector.

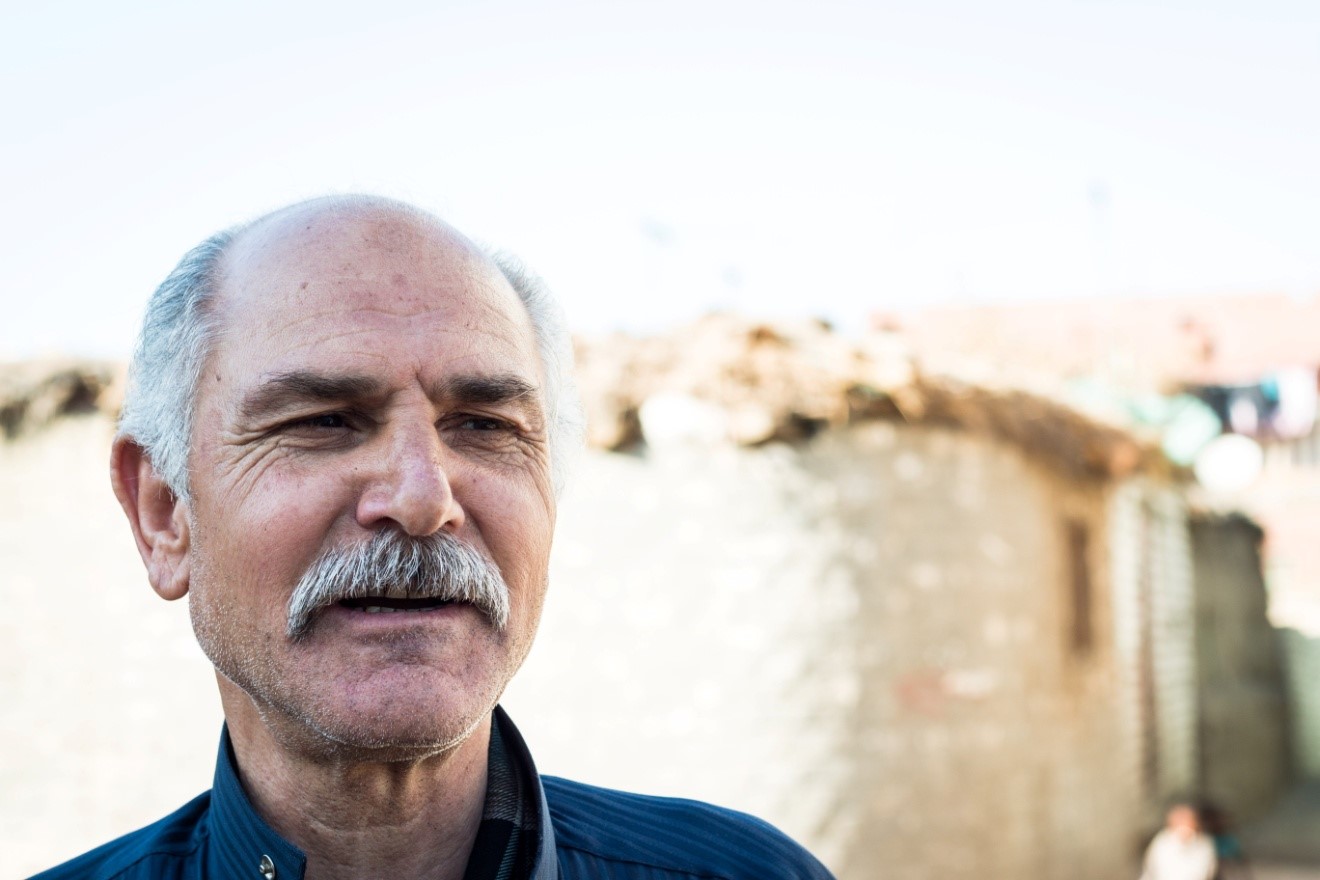

This process requires two trips to Cairo and another two to Zagazig, the capital of Sharqiyya, and it costs around LE 298 ($US 38). “The fees are average, but the 15-day hassle is what makes the process extremely difficult to afford. Afterwards the sustainability of affording school fees is not guaranteed over the years,’’ Eid el-Namooly, mayor of Fadel’s Island, said.

The percentage of students is 70 percent males to 30 percent females. Parents believe their daughters can carry out successful lives without going to school.

Only five percent of the students finish their education and go to college, where they are required to pay in US Dollars or UK Sterling. Palestinian refugees only receive a discount if their mothers are Egyptian, which is the newest adopted solution. If the mothers are Egyptian, the students pay only 10 percent of the original fees.

Since 2000, around 10 percent of Palestinian males on the island have married Egyptian women from neighboring villages to facilitate legal procedures and secure a better future for their children as the children will obtain Egyptian nationalities.

The island has only one classroom that is poorly equipped to fit 20 students. It’s used during school season to give advancement classes to students who are already enrolled in public schools. During summer, it’s used for literacy classes for adults.

Mohamed, a man of mid-thirties and a teacher at one of Abu Kabir’s public schools, volunteers to teach children on the island three classes per week along with his wife who volunteers once per week. “Three days a week, we study Arabic, three others we study science and art, and Friday is off,’’ he said.

Om Fadel volunteers for the summer literacy classes, where residents are taught the importance of having ID cards, birth certificates, risks of early marriage and the right to education and health care.

Applicants are usually craftsmen or mechanics who need to apply for a driver’s licence or another specific reason. They’ve grown accustomed to living their lives without having to be educated, the island’s mayor, said.

As a result, children turn out clueless about Palestine and its history. Upon meeting more than 20 children, only one — Nedal, 15, who aspires to become a plumber — could recite the Palestinian national anthem, Fedaee (my sacrifice). The anthem, Fedaee, was declared Palestine’s national anthem in 1972.

Naema, 30, a mother of four infants, said she doesn’t know whether she’ll enroll them in schools or not, as the cost is too much, and the burden is too heavy. Naema believes she’s living an ordinary life. “I have a fan and a TV like the civilized do,’’ she added.

Dirty, Miserable Barbies

A call for medical care -a call for help.

Children look like contaminated candy. Their blond hair, blue eyes, and charming smiles are ruined with mud on their faces. They have a hideous odor that seems to make houseflies follow them everywhere they go.

Even on a small island, children are taught not to befriend everyone. “My mother warns me not to play with them – they don’t dress nicely. They buy ice cream on Wednesdays,’’ Omnia, eight, said.

Some Wednesdays for children of the island are a modern-day equivalent to Egyptians’ weekends away in the North Coast. On those Wednesdays, parents buy their kids clothes, and everything they want within their reach. To Omnia, buying ice cream isn’t enough for them to be her friends.

In broad day light, you won’t find an adult walking in Fadel’s island; they’ve all gone to work. The harsh financial conditions of the residents have forced them to accept any available jobs even if it harms them. They have started working in recycling plastic since 2007.

“It’s a job that requires minimum experience and it pays up to LE 3,000 per month,’’ el-Namooly said.

The health conditions of children are constantly deteriorating. Hereditary diseases are very common due to inter-family marriage such as diabetes, deafness, congenital diseases, cleft lip and palate, and brain clots.

Upon the rising phenomenon of working in recycling plastic and garbage in 2007, they started spreading awareness of the potential outcomes that could result from dealing with garbage on daily basis, el-Namooly added.

The entire population is suffering from health problems. The nearest pharmacy and hospital are two kilometers away. Medical convoys visit them once or twice a year maximum.

‘’We suffer from lifelong diseases like cancer and kidney failures. Whenever we seek help from local hospitals, we’re asked to pay as foreigners. Although we are born and raised in Egypt and financially incapable of paying huge costs – it’s frustrating. We ask the Ministry of Health to overview our situation, as Egyptian born and residents for more than 10 consecutive years, to be treated as Egyptians,’’ el-Namooly said.

There are many other occupations, but recycling pays best. Others work as seasonal crop harvesters, sheep raisers and mechanics in a lower percentage. The average income of those jobs is LE 1,500 to 2,000 ($US 191.5 – 255.3). The mayor, who was skeptical about sharing the inhabitants’ affiliation to recycling in the first place, admitted that this job could potentially have crucial health problems on the residents.

During Abdel Nasser’s era, attempts to include Palestinians into any refugee organizations or the UNRWA were dismissed, as they were to be treated as Egyptians. After the murder of Youssef al-Sebaee, Egyptian author and then-minister of culture, by Palestinian guerrilla in 1978, the perspective changed 180 degrees.

In an attempt to improve the health conditions of the residents, el-Namooly’s father and late brother started a small medical facility in the heart of Fadel’s Island with the financial aid from former Palestinian Ambassador in Cairo, Barakat al-Farra and Vice-President of Palestinian Women’s Committee, Amal al-Agha. Although the building is still under construction, the island’s residents are clueless about how they are going to manage it. So they’re moving one step at a time, el-Namooly added.

Residents of the island wish that the government or any NGO would step in and help in finishing the medical facility.

Paper Cuts

Residents of the island demand the government’s attention for being one of Egypt’s poorest villages. Complaining about their incapability to acquire the money necessary for residency papers’ renewals, education or medical care, they want to be treated as Egyptians.

“In 2011, all eyes were on us, media outlets were racing to feature us in local and international news, but it was all for the sake of media propaganda and writing on a deserted land and people. Many Egyptian and Arabic newspapers wrote about us, such as al-Masry al-Youm, al-Youm al-Sabea, al-Badil and others. Yet, none of them really fixed or helped in fixing any of the problems they’ve so eagerly written about,” said el-Namooly, Om Fadel and Abu Yassir.

What was even more disappointing to the island’s residents was that none of the NGOs, charity or service organizations offered help after the widespread media buzz. ‘’We rely on no organization’s help; we are purely driven by personal efforts and occasional donations,’’ el-Namooly said.

Every five years, Palestinian refugees change their postal account in the Mogamma for LE 105 per person. The fees required – if a Palestinian is categorized as A or B (Palestinians before and right after 1948) – are LE 12 ($US 1.53), while categories D and H (post-1967 refugees) pay LE 160 ($US 20.43).

‘’It’s not like that travelling permission could take us anywhere. We can only travel to Sudan or Mecca to perform Hajj, nothing more. We use this document like it’s our ID card while in fact it only permits our stay in Egypt,’’ el-Namooly said.

A social solidarity law issued in 2010 and activated after the revolution in 2011, stipulated that stipends to foreign residents would stop.

Even governmental supply has stopped since 1986. It now operates using the national ID number, and they have none. So it stopped for good. They started buying from the regular supermarkets like any regular middle-class customer, when in reality they’re not even remotely close to that. “We don’t want to generalize a rule for all Palestinians in Egypt, some of us are rich, we’re just saying we are not,’’ Abu Yassir said.

“Aside from the legal complications, it’s safe to say that I’m being treated fair and square in everything else associated with the executive sectors but what we need is a lawful treatment not a personal one,’’ el-Namooly said.

Colours of Palestine

Although the majority of residents have never been to Palestine, they hold on to the traditions they have inherited from their ancestors.

“We still solve our problems and hold our discussions in a traditional Diwan-Khane – a tribal gathering in which people discuss important matters, such as social or political affairs. At the Diwan-Khane, we resolve marriage problems and disputes between families, and we sometimes solve problems for Egyptian neighboring families, too,’’ Abu Yasir said.

“We still drink our traditional blank coffee made on coal. Sure we drink Arabic coffee, too but ours is never forgotten,’’ el-Namooly said.

The women still wear the traditional handmade Palestinian dress for weddings and celebrations. It’s an everlasting source of national pride for them.

They try to teach children about the Prisoners’ Day, Earth Day and the memory of the Nakba (otherwise known as the Palestinian exodus) as much as they can. “We try to send delegations of 15 or 20 persons to Cairo to attend events held in the Syndicate of Journalists and the Palestinian Workers Committee. We also teach the children the Palestinian map and where Beersheba is located,’’ the mayor added.

“We previously used to master the skill of raising camels but we stopped in the ’70s and people have shifted to sheep instead. The only remaining family that still works in camels is Aunt Nafla’s,’’ el-Namooly continued.

Fadel’s Island residents know more about Egypt than they do about Palestine. Ninety-nine percent of them have never been there; their accent is a hybrid between Levantine and Egyptian.

Refugees on the neglected island demand to be looked at as Egyptians. Because to them, Egypt is the only home they have ever known.

The residents are overwhelmingly satisfied with what they have. They don’t aspire for much. In a way, they’ve created their own Palestine in the heart of Abu Kabir.

Despite the harsh conditions that are hard to miss, one feature that prevails Fadel’s Island is how generous the residents are. They are always genuinely happy to see a visitor; the children long for a new hide-and-seek partner, the educated elites seek someone to discuss foreign politics, the wives want to hear about the rest of the world and the old ones desperately need a good laugh.

Comments (15)

[…] The Palestinian Refugees of Fadel’s Island: Living on the Margin in Egypt – Upon meeting more than 20 children, only one — Nedal, 15, who aspires to become a plumber — could recite the Palestinian … So they’re moving one step at a time, el-Namooly added. Residents of the island wish … […]

[…] Dans un long reportage sur place, le site d’informations Egyptian Streets raconte leur histoire. […]