“Non veiled [women] and no pets allowed,” those are the booking rules that Nevert Rahmy, mother of three, received from a beach resort in Egypt while inquiring on Instagram.

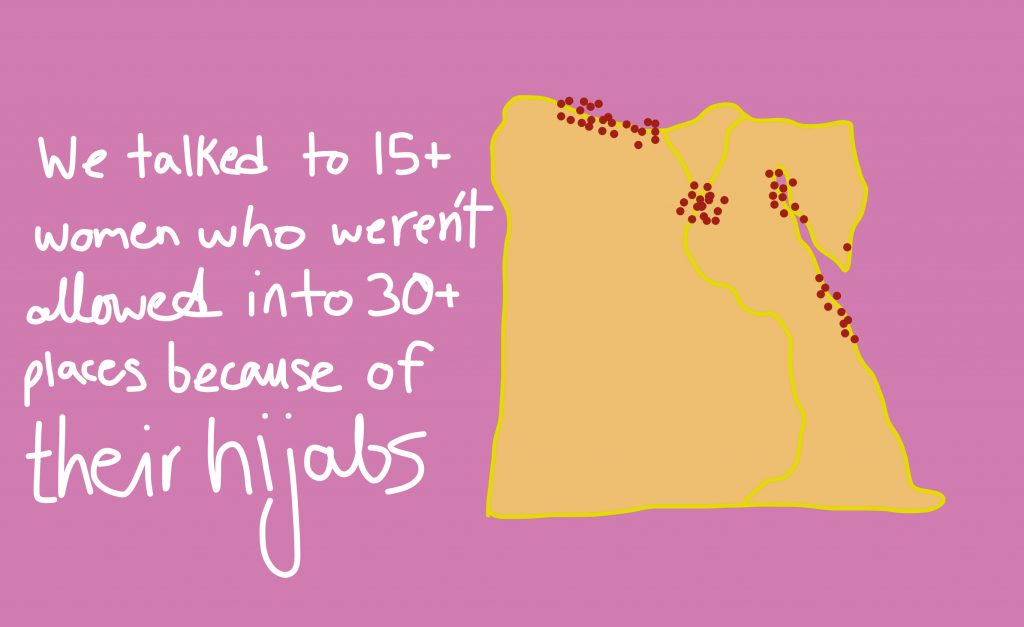

On July 10, Rahmy’s Facebook post, detailing her experience with the resort that indicated pets and veiled women were not allowed on their premises, received just under 1000 shares. The banning of veiled women, also known as hijabis, from upscale resorts, bars, and restaurants is nothing new in Egypt. According to the testimonies that have been shared with Egyptian Streets, in the past few years, the number of establishments enforcing the discriminatory rule has vastly increased.

After increased social media outrage, Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities representative Ali Ghoneim announced on the DMC television channel on July 20 that it sent a release to all compounds and hotels. The release entailed that the burkini, which is a full-body swimsuit for veiled women, is allowed everywhere, and that anyone who is prevented from this the right to swim in it is to contact the Ministry of Tourism which will then take the suitable legal action towards the establishments with the ban.

Hijabis Speak Up

Since Rahmy put on the veil 13 years ago, she experienced the discrimination in several places, with her most recent encounter being in a bistro on the North Coast. Her family told her they called the manager and asked for an exception to be made for her in advance, and she put on her headscarf in the turban style for the occasion.

“These young men at the door, as old as my children, told me ‘no, sorry we can’t let you in’. I was shocked,” she told Egyptian Streets.

Rahmy’s father told her that she should have called the Tourism Police, but while she felt extremely upset, she did not want to make a scene. The incident, however, that prompted the Facebook post was the opening of a private beach that Rahmy inquired about.

She received a long message back from the resort that highlighted “no pets, no veiled women.” She was taken aback, but was able to reach the resort with her complaint. They apologized and told her they were not aware that the rule was being imposed.

“The next day, the hotel and beach called me, and I posted their apology [online]. So, since their first day, they’ve allowed veiled women,” she added.

Rahmy learned that hotels were not allowed to ban any kind of person from entry when she personally contacted a Ministry of Tourism official who notified her of the release that was announced on July 20.

“Recently, the Prime Minister introduced the bullying law and the harassment law, and this [discrimination] is the same thing, no one can tell you that because you’re veiled you can’t enter a place,” she said.

Rahmy’s post was followed by a new wave of women sharing their experiences, and listing places where they were not allowed to enter.

A few days later, Facebook user Merna ElWosseif shared a similar experience via the platform, where she was asked by the lifeguard at a North Coast establishment to exit the pool as she was wearing a hijab swimsuit, to which she tried to explain that the outfit was a surfing suit.

ElWosseif was told “this isn’t the first incident at the pool and that other owners take pictures of hijabis swimming in the pool and send it as a complaint to [the] managers.”

In response to the recent events, we reached out to various women, asking for their stories and experiences with wearing the hijab in Egypt. A common response was that none of them had experienced this kind of problem outside Egypt, and if they had, it would have been considered an act of religious discrimination.

Navigating the Labyrinths of Hijab-free zones

Passant Ayman, 22, told Egyptian Streets that when she was at a popular Cairo hotel, she went to the bar to get a bottle of water.

“It was this bar, literally in the middle of the hotel; it was just an outdoor bar with a few high tables around it, and I went to get water. I didn’t even sit. I just asked for a bottle of water, and the waiter was like ‘Can you stand further away while I get you the water because you can’t be seen this close to the bar.’” Ayman said.

At a different establishment, while booking, she was told that if there was a veiled woman in the group, there had to be a certain ratio of non-veiled women to veiled women.

Nour El Nayal, 23, said that to get into a “halloween party,” at a restobar, her friend had to wear her hijab as a turban, let out a couple of hair strands and make it part of the costume, so the bouncers would let her in.

Jana*, 22, told Egyptian Streets that she had gone to a North Coast hotel twice several years ago, but the third time she went two years later, they had written at the pool rules that no burkinis were allowed in their main pool.

“I went into the pool, then the lifeguard comes around and says ‘Sorry burkinis aren’t allowed in this pool.’ I asked him ‘why?’ and he said ‘it’s the rules,’ so I told him that ‘my family’s here, and I want to stay here’. He said ‘You can go to the other pool, as this is the rule’, so I was like ‘okay’…he comes back to say if I stay in the pool, the other hijabis are going to want to go in too. So, I just stayed in the pool till they closed,” she said.

Resisting the rules is an option that some choose to pursue in defiance. However, not every hijabi is patient enough to argue their way into every experience these establishments deprive them of.

Salma*, 23, shared with Egyptian Streets that she routinely avoids any place where hijabis might be banned to avoid any embarrassment.

“Society has forced so much hate and judgment on burkinis and hijabi swimsuits, so I’m really uncomfortable wearing it. I never wear it anywhere with friends. I only wear it to the beach that is in front of the house where no one goes,” Salma said.

Yara*, 18, had a similar experience of watching her mother get asked to leave a pool in a resort in Ain El Sokhna for her burkini.

“This happened about 12 or 11 years ago, I was a kid, so I wasn’t allowed to listen to the whole conversation between my parents and the manager, but the public embarrassment and the incident is still very vivid in my mind,” Yara explained.

She said that after only five minutes where her mother went into the pool, she was asked to leave.

“My dad gets upset and asks for the manager, all while my mom is asking him to drop it because she doesn’t want to make a fuss,” she added.

Yara said their excuse for banning burkinis is that it “ruins the pool filters” and it is “just not allowed as part of the contract.”

However, she highlighted that during the incident, there had been foreign tourists wearing cotton t-shirts in the pool yet no one “dared” to speak to them. Yara and her family cancelled their reservation and left for Cairo the same day.

Rana*, 21, shared that prior to booking at a beach bar in the North Coast, she and her friends were asked for their social media handles. She assumed they would tell her she wouldn’t be welcome when the booking agents spotted her veil, but the booking unexpectedly carried through. However, when she arrived at the location, she was told she would not be permitted inside.

“They told me you’re welcome to come anytime, just not during the weekend as they wanted to create a certain “vibe” and, apparently, me wearing a turban would ruin that for them. I asked her [the beach bar employee] why she didn’t mention that on the phone or anywhere on any of their social media accounts. She was honest with me and said that writing this down would create problems for them, so they don’t mention it on the phone or any of their social media accounts,” she explained.

When Rana asked the bouncer how, then, was she supposed to know, she was dismissively told that it’s a bar, and it’s expected that she knows they wouldn’t be able to let her in.

When booking a popular restobar, Amenah Abouward was told that her “diverse dress code,” meaning hijab, was only allowed Friday and Saturday afternoons until 7 PM.

Sarah Abouelkhair, 24, had a similar experience with the same location.

“I arrived with one of my friends. At the door, the bouncer told her [the friend] to go in and said I couldn’t. I asked him why, he told me it’s because of my veil and said ‘if you take it off, you can come in.’ He told me ‘You can just put it as a turban and come in’. I got super angry and left,” Abouelkhair said.

“Like hearing the Adhan”: Judgments and Justifications

Maryam Hisham, 25, told Egyptian Streets about the same location as Amenah and Sara, where she had an almost identical experience despite getting a prior exception from the managers.

“It’s very systematic in Egypt; it’s very classist. It’s not just the owners of the place that don’t want hijabis to come in, it’s also the people inside. They’re very uneasy about hijabis being in the place,” Hisham explained.

Hisham was traveling with friends who were going to a club in the North Coast when they had a discussion.

“I was saying how awful it is that they can go in and I can’t because I’m veiled and that it’s very classist. They told me ‘no, if we see a veiled girl inside, it’s like hearing the adhan [Muslim call to prayer] so we will always remember that we’re drinking and we’ll feel guilty. That’s why we don’t like veiled women to be in those places’,” she added.

According to the testimony of the aforementioned women, there is a common justification used by both the individuals who go and the establishments themselves, for the ban on hijabis in certain places, because these establishments serve alcohol or encourage activities that are deemed ‘haram’. This justification is then used as a reason to put rules in place to ban hijabis from these establishments for the sake of the affected parties that frequent the locations.

Another justification used by these places, that include restaurants, bars, clubs, pools and beaches, is that veiled women are not allowed inside “out of respect for the veil”. In a 2012 column for Daily News Egypt, the author responded to such claims stopping her from entering a restaurant by saying that she did not expect it would be “decided on my [her] behalf that I [she] should not be exposed to the debauched world of dining.”

The Hijab’s Ever-Changing History in Egypt

The hijab has often been a source of contention in Egypt. The veil has come to represent a lower social class due to its divide from the West at a time when there’s a desire for all that is Western.

When Khedive Ismail came to power in 1863, he spent 16 years ingraining western culture into Egyptian life, with his goal being to turn Cairo and Alexandria into European cities.

The elite status of the British was established in Egypt when it became a colony. Physical and social remnants of that time still remain, such as the Gezira Sporting Club which was built for exclusive use of the British army. Later, in 1952, it was nationalized and became public, however it still stands as a symbol of elite westernized Cairo today.

A study conducted by Ain Shams University cites that starting with Egypt’s semi-independence from the British in the 1930s, men and women celebrated the participation of “unveiled women” in the reform movement. Women’s roles later shifted with the re-emergence of Muslim fundamentalist groups, and there was an increase in women putting on the veil.

This started an almost century-long paradox of a large percentage of women putting on the veil while an underlying colonial legacy remained that championed the unveiled woman and the “leftover morals” from the days of colonialism, where what was Western was seen as more elite than what was traditional.

Many women turned to the veil as a symbol of political protest and a rejection of Western culture, while many others considered it a symbol of religious piety, and some consider it both, the study explained.

Other studies have shown that in more recent years, the hijab has grown once again to be seen as a symbol of backwardness and extremism by some in more ‘elite’ communities.

In 2006, then-Minister of Culture Faruq Husni publicly stated that he considered the hijab regressive. Later in 2013, Bahaa Anwar, then-head of the fringe Secular Party of Egypt, announced the “The International Day for Taking Off the Headscarf,” campaign, though it never took off. Most recently in 2018, well-known author Cherif Choubachy called for the unveiling of Egyptian women in his book “Urgent Message to Egypt’s Women,” claiming that the neo-veiling movement was motivated by solace in religion after the 1967 war defeat, not by authentic faith.

As early as 2009, it has been reported that hijabis were being turned away from bars or lounges, for their “religious appearance”. In 2015, many women seemed to have had enough, with a major wave of social media posts calling out the issue as a classist and discriminatory one, with hashtags such as #HijabRacism and #مش_من_حقك_تمنعنى. From the context, the word ‘racism’ in this hashtag refers to discrimination, and two concepts that are often conflated.

In 2016, social media influencer Sara Sabry shared a video saying that, while trying to book a restaurant for her birthday celebration, the booking agent told her that her guests would be more than welcome, but she would not be allowed in.

There is also a noticeable trend of discrimination against hijabis in the workplace, with job listings requesting only unveiled women, or simply rejecting hijabis who apply, to maintain a certain ‘look’ for their companies.

Notably, however, the traditional culture that remains does not encourage women to wear less modest attire, and patriarchal values of policing women’s clothing are not restricted to solely religious or social values.

The Legal Implications

Despite the recent release from the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities informing that establishments may not refuse entry to veiled women, there were many conflicting opinions in the past several years about the liability of enforcing such restrictions. A 2012 Egypt Independent article stated that executive human rights lawyer Gamal Eid affirmed that establishments cannot deny service to paying customers by law.

In 2015, Mervat Tallawy, the head of Egypt’s state council for women said that Egyptian law does not regulate on such issues, in an article published by AlArabiya.

Despite Tallawy’s assessment, in 2015, following a number of high profile cases, Egypt’s then-Minister of Tourism said that any restaurants or tourism facilities found to be banning women dressed in the hijab from service will be shut down.

More recently in 2017, lawyer Ibrahim El Salamony ensured that there is no legal text that criminalizes “no hijabis” signs. However, that does not negate that there are possible legal consequences for doing so as it opposes the constitution, according to others. Thus, many institutions enforce these rules without announcing them to the public on a large scale.

For a country whose population estimated close to 90 percent Muslim in 2016, there is arguably some irony in the fact that the mere presence of a hijabi in a bar would constitute implicit judgement of one’s behaviour. However, the policing of women’s attire, be it a burkini in a pool, a hijab at a bar, or a pair of shorts in the street, is nothing new.

Women are starting to speak up, and if Rahmy’s impact with the Ministry of Tourism is any evidence, change may indeed be on its way.

*The names of these women were changed at their request for privacy purposes.

Comments (2)

[…] and restaurants – received backlash for restricting veiled women from entering their venues. This sparked several online movements throughout the years, with women calling out venues and affluent […]

[…] out this Egyptian Streets article on the different ways wearing the veil is either enforced or not […]