Creativity is a buzzword in most industries today, with the corporate agenda becoming increasingly enamored with the idea of effectiveness over traditional work cycles.

From nine-to-fives to near-total flexibility, workplaces worldwide have seen a shift in personality: sleek, modern offices, ping-pong tables and ambient music, rooms decked with beanbags that offer the illusion of comfort. The Guardian describes these as neoliberal workspaces, or offices that take pride in their dynamic organizational structure and claim to be more effective than routine-based work-cycles. The more spontaneous and independent the work atmosphere, the more effective. Although popularized in theory back in the nineties, this shift didn’t reach full potential before the early to late 2000s.

Egypt’s experience with the flexible workspace first appeared a little under a decade ago, where the creative sector – brimming with youthful, up-and-coming entrepreneurship – decided to latch onto the concept of hybridizing work and play; no longer was it fashionable to focus for hours on end in the company of a computer screen. Individuals were given the liberties of working remotely and having ritual smoke breaks, they were granted the freedom to plan their own days down to the minute, even within the confines of the office.

For a while, the arrangement was an ideal one: when a break was needed, it was had – and the subsequent energy-boost would inspire more efficient, speedy work.

But over time, the popularity and alleged benefits brought in by neoliberal workspaces were brought into question. A 2014 entry in the journal Social Currents describes the actual successes of neoliberal policies as “debated and best described as mixed.” Despite the increased awareness of mental health management and realistic work processes, flexible workspaces produced their own set of anxieties – from 24-hour work-cycles to questionable salaries.

Work Hour “Gymnastics”

One of the classic critiques of the nine-to-five model is its tedious, repetitive – and often inconvenient – nature. The private sector in Egypt, most notably in advertising and marketing industries, has championed the concept of doing away with the unloved and unmissed tradition. While many firms require office attendance five days a week, employees are free to come in as late or early as they like – insofar as, according to one account manager, “the work was done at the end of the day.”

In a space with continuous clientele and massive output, advertising firms are seen as the key example of the 24 hour workcycle: although an individual could start their day at noon, after a hearty breakfast and a dark brew, they were said to spend upwards of ten hours at the office in order to ensure the completion of their tasklist. This included any and all tasks that were introduced throughout the day, despite not being on the original schedule.

“I started smoking [because of it], actually,” joked Mariam Yasser, 27-year-old account executive at a Zamalek branding firm. She laughed through the phone receiver, incredulous. “I smoke a pack and a half now. I still work there, but it’s not for everyone. You need to really love it to hold out.”

Yasser emphasized that she did enjoy her job, but she was more disappointed in the disorganization that seemed to come with it.

“There’s a lot of internal miscommunication. There’s a lot of rude clients, and management won’t always have your back. If a client wants you to meet on a weekend, you’re go[ing] to have to do that,” she explained.

This trend of employee compromise, according to content creator Hashim Ramzy, 31, stems from the idea that companies are making equivalent compromises for the sake of their employees’ comfort, therefore, it becomes harder to deny them. The freedom of coming and going, he believes, is the root of the issue.

“You’re free, el mas’ala heby [it is all done informally and haphazardly]. I can’t say no to finishing something if they let me come in at two, you know?” Despite hours ranging from eight to twelve per day, Ramzy’s company doesn’t pay overtime. He firmly believes “they’d make [him] stay late even if [he] did come in earlier, so [he doesn’t].”

Still, Yasser claimed there is some good to the “gymnastics” of her schedule. With the hustle and bustle of Cairo, she brings up the matter of convenience.

“I don’t have to leave right in the middle of [evening] rush hour, and waiting in the office doesn’t feel as lonely when everyone’s still around, waiting it out. It’s the same for the morning, too. I don’t have to deal with the school bus [and] bankman traffic rush at nine [a.m.],” she said.

When asked whether the long hours were worth it, she took a moment to think.

“I don’t know. There’s a lot of good in the [advertising] industry, even if they squeeze you, you learn a lot. I guess that’s part of the payoff. If you want to be in the creative field, you give up predictability a little. It’s not always fair, but there’s a choice you make,” Yasser explained.

Ramzy’s thoughts were similar in essence, but different in opinion. A common strand of conversation was the difference between what he called “the creatives” and “the managers.”

“It’s not that we [the creatives] work harder, but there’s a really tough expectation on you to pull all-nighters and prove yourself,” he said. “I leave the office really late, and the [account executives] are never here past seven [p.m.]. That’s not that late for Egypt.”

Ramzy went on to describe his workflow, saying that he remains in the creative sector because he enjoys the artistry of it, and preferred work in the evenings.

“But I don’t really get the chance to socialize with anyone but co-workers. I live in El-Shorouk [a satellite suburb to the east of Cairo], so by the time I get home, I’m exhausted. I go to bed and wake up late [the next morning], and yeah, on it goes.”

Artists: Undervalued and Underpaid?

“I want to be honest with you, but I don’t think I can do that without getting sh*t for it,” said ex-content creator Malak Hamdy [alias] when asked to share her real name. Once she was reassured, Hamdy corroborated Ramzy’s thoughts based on her experiences at a Cairo-based advertising firm.

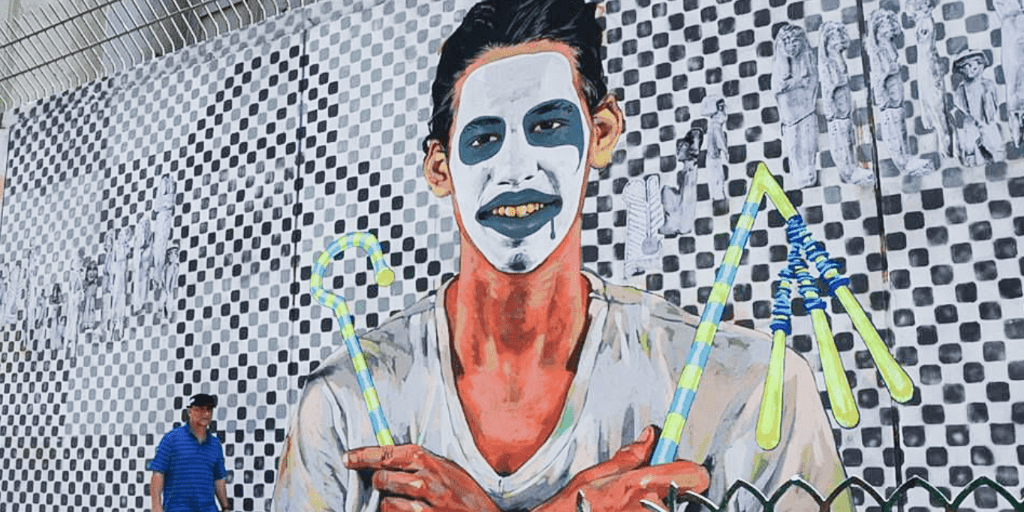

“You’re there for hours. They expect, [be]cause you’re a content creator, that work is your personality and life – because it looks fun and colorful,” Hamdy said.

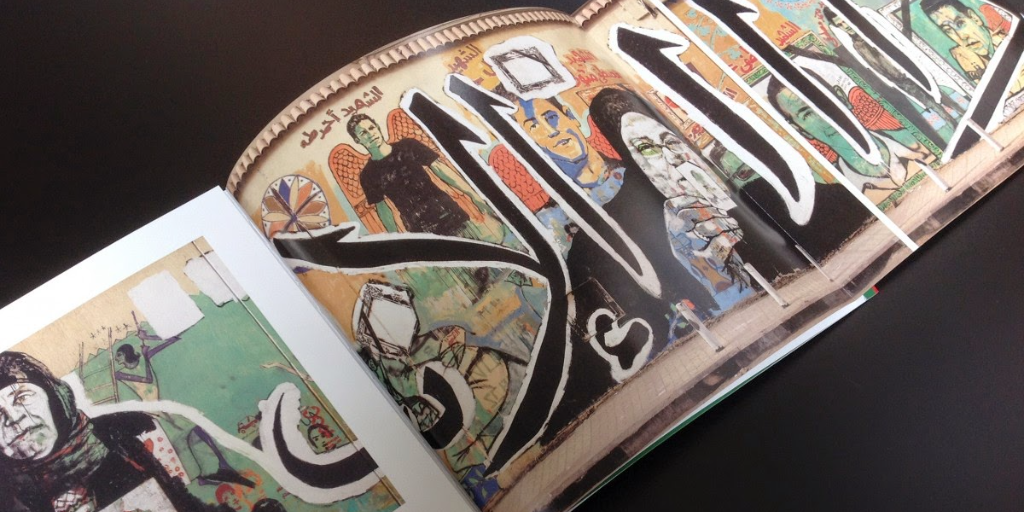

Her statement falls in line with claims that creative fields, such as visual or conceptual arts, are often overlooked as easy and overpaying. In an interview with The Missing Slate, artist Shanzay Subzwari mentioned how, in her experience, “[p]eople think art is easy; all we have to do is make a painting and then sell it for thousands. What they don’t know is the struggle, practice and journey one has to take to be able to reach that stage.”

Hamdy was also quick to point out the salary disparities between “real art” and graphic design.

“We’re not paid that well. And at least [in this firm], you’re not exactly paid for each extra hour. If you’re a real artist you’ll make thousands but designers get looked at [with pity] since people think it’s not a real job,” she said.

Egypt’s National Wages Council has recently raised the minimum-wage for the private sector (EGP 2400 per month), according to the Ministry of Planning. Despite this, Hamdy explains that many with degrees in the arts are not compensated fairly.

“I can’t [run] a whole house and kids with the pay I get.” Although she’s quick to say that she herself doesn’t have children, and is not yet married.

It’s worth mentioning that Egypt is not alone when it comes to struggles in the creative sector. In an online survey by GraphicDesign& (available on It’s Nice That), over two-thousand designers were asked about whether or not their pay is representative of their work.

“On average, designers earned less than their partners but worked for longer hours,” states the report, and only 55 percent expressed satisfaction with their career.

“The cocktail of creativity and commerce is a double-edged sword,” wrote It’s Nice That, reporting on the findings. “One of [the] key questions was ‘what is the worst/best thing about being a designer?’ Many people gave the same answer for both worst and best. One such answer says it all: ‘you never switch off.’”

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features, and more stories that matter delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here

Comments (2)

[…] Source link […]

[…] المصدر by [author_name] كما تَجْدَرُ الأشارة بأن الموضوع الأصلي قد […]