“[Some] saw him as a lonely guru, reminiscent of Old Testament prophets, promising that the world would reap misery for not listening to the truth of his message.”

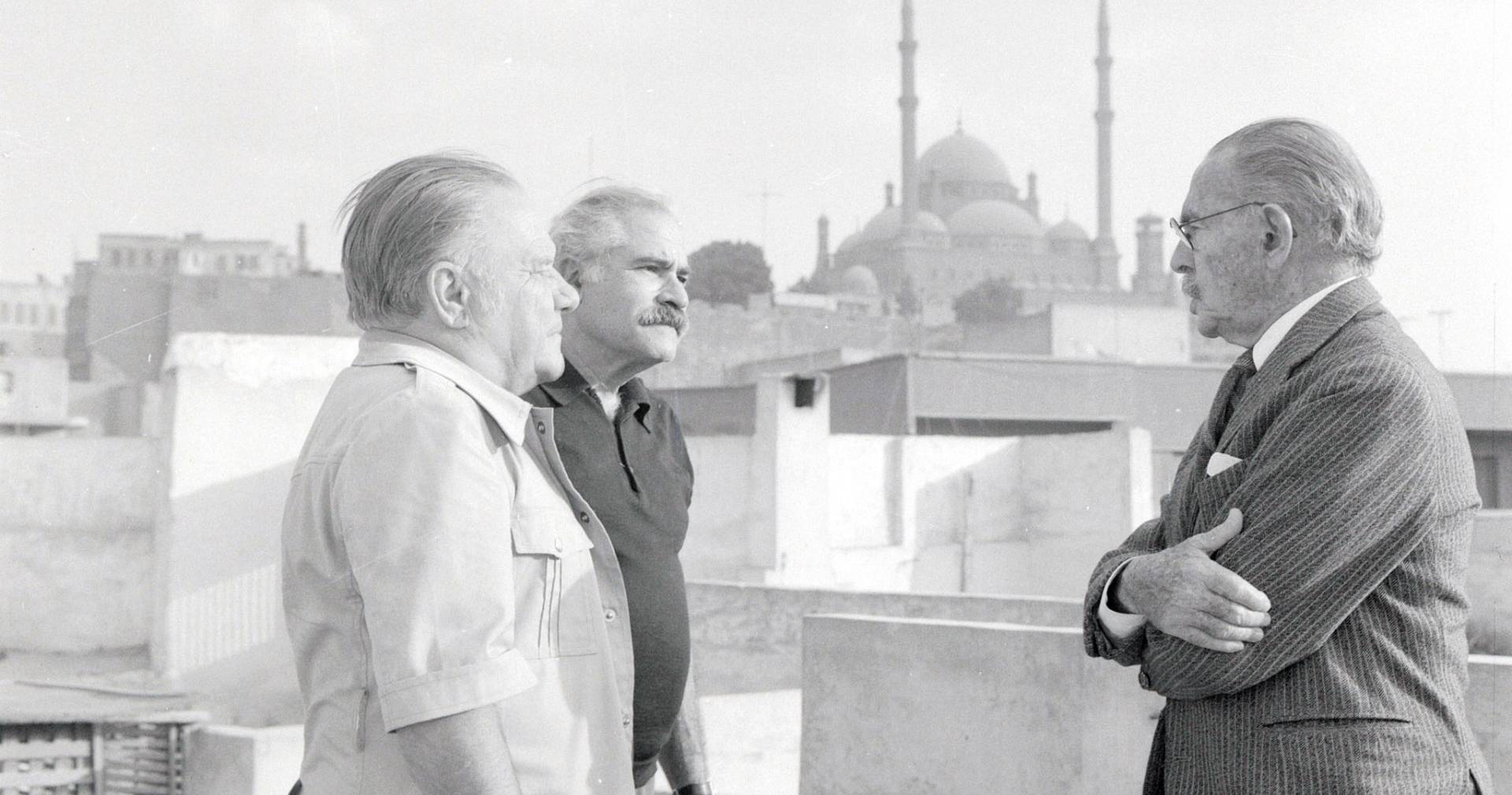

These words, written in a study dedicated to Hassan Fathy’s legacy, paint a mysterious picture of the life and work of the controversial, yet highly celebrated, Egyptian architect. But who was he, and what makes him stand out until today as one of the most unique, timeless, and internationally recognized Egyptian architects of all time?

Born in 1900 in Alexandria to an upper-middle class family, one notable peculiarity in Fathy’s six-decade career is that much of his work – including New Gourna, the village that became his best-known project – was neither urban, nor for the well-to-do.

Located in Luxor, New Gourna was a prime example of the philosophy ingrained in Fathy’s designs. Architecture, he believed, was for human beings. At the core of his concepts were the needs of those who would use his buildings. In the case of New Gourna and many of his other projects, those who used his buildings were Egypt’s rural poor, whom he centred in most of his work.

“We need a system that allows the traditional way of cooperation to work in our society. We must subject technology and science to the economy of the poor and penniless,” said Fathy, who became known as ‘the architect of the poor’.

His work also rejected many elements of internationalist modernism and embraced traditional styles, approaches, and materials, believing that they were best suited for the environment. He valued indigenous insights on architecture and believed that they were there for a reason; a direct result of indigenous needs.

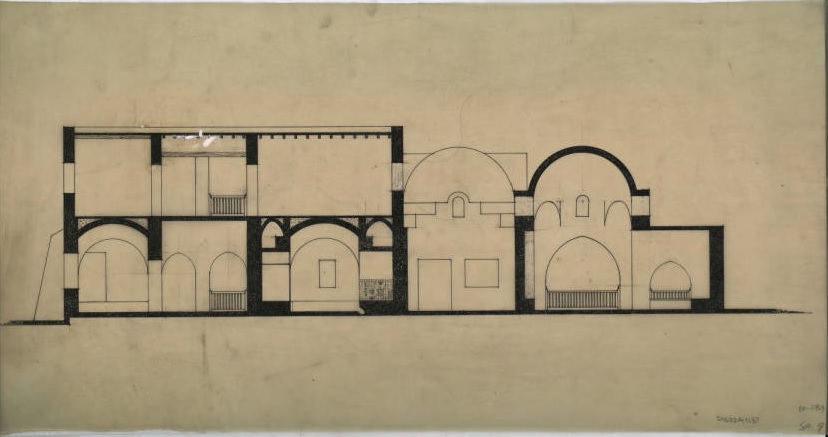

While building New Gourna, for example, he championed cultural authenticity by using mud bricks as his main building material and designing domed ceilings as is common in Upper Egypt.

Fathy, whose work focused on developing countries, the Arab and Muslim world, and particularly Egypt, believed that straying too far from traditional concepts and instead opting for culturally alien designs and materials, would with time encroach on the indigenous cultural identity.

These beliefs marginalised Fathy for some time within the Egyptian community of architects, which initially did not fully accept his rejection of modernism, but Fathy was immovable. Eventually, still within his lifetime, he was vindicated.

Gradually, more and more people in Egypt and the rest of the world began to see that what he was proposing was a different, more locally-centred form of modernism, which is far more sustainable and likely to preserve unique cultural identities.

Fathy was honoured many times for his work and architectural philosophy, receiving awards such as the first Aga Khan Chairman’s Award ever given, as well as the Right Livelihood Award in the first year of its inception, both in 1980. His book, Architecture for the Poor: An Experiment in Rural Egypt, in which he evaluates and discusses his project at New Gourna years after it was built, has become a staple for architecture students around the world.

Today, over three decades after Fathy’s death, his ideas are still proving to be relevant and insightful, perhaps even more than in his own day: for all the excitement about Egypt’s current construction boom, with developments in new urban centers such as the New Administrative Capital or New Alamein City, some are voicing concerns very similar to the core of Fathy’s message of humanism, cultural authenticity, and sustainability.

With expensive, modernist designs that do not tie in local designs or materials, Fathy’s words from 1969 are recalled:

“In modern Egypt there is no indigenous style. The signature is missing; the houses of rich and poor alike are without character, without an Egyptian accent,” he writes in his book Architecture for the Poor: An Experiment in Rural Egypt. “The tradition is lost, and we have been cut off from our past ever since Mohammed Ali cut the throat of the last Mamluk.”

Comments (6)

[…] The Egyptian ‘Architect of the Poor’: Hassan Fathy and Why His Vision Still Matters […]

[…] المصدر by [author_name] كما تَجْدَرُ الأشارة بأن الموضوع الأصلي قد […]