Some people are nomadic for a short period of time, while some for years, months, or even their entire lifetime – constantly searching for ways to adapt, reconnect, and ‘put down roots’ in a certain place.

Yet while some are nomadic out of choice, others out of necessity.

Since moving to Egypt around seven years ago, I’ve always felt the urge to reassure people that I was just like everyone else; that I’m not a foreigner, a stranger, or a nomad with no place or identity. I’ve always felt the urge to ‘prove’ my Egyptian-ness, until I finally opened myself to the reality that I may possibly live as an eternal stranger in my own homeland.

People don’t really talk about the ‘out of place’ child – the child who has spent years living outside of their homeland and has developed no real or meaningful connection with the place. People don’t really think it is an issue to be tackled, or even worthy of being tackled. I am either in or out, Egyptian or non-Egyptian, belong or do not belong.

Like a child wandering aimlessly, there is no clear pathway to follow, and so you are forced to build your own ‘house of being’ – your own path to find true belonging and connection. You struggle with an unusual kind of pain, one of emptiness that is hard to articulate because no one ever tries to help you understand what you are feeling or experiencing.

Every place I went, the question of my nationality was always brought up, and if it wasn’t, then I would find out later that they questioned it among themselves. “They didn’t think you were Egyptian,” someone told me a few days ago. “Aren’t you Egyptian? Why don’t you speak Arabic well? This is our language,” another person once told me. Wherever I went, I carried the weight of having to explain why I speak or act in a certain way, or why I misunderstand most of the phrases or slangs being said.

It may seem like a trivial issue for anyone that holds their ground in their homeland, but for someone like me, it always feels like I am walking around with no roots, no base, and no foundation, as though I am walking on water while everyone else is walking on a firm ground with ease and confidence.

When my sister and I were growing up in Abu Dhabi, Egypt was an imaginary world where we saw our relatives, reconnected with family friends, and celebrated birthdays, weddings, or national holidays. Because we were children, Egypt was a place for celebration.

As we got older, we came to realize that it was a mythical homeland. Egypt only belonged to our parents – they knew its language, culture, traditions, and history. Relatives grew older, new generations came to life, older generations passed away, and friends gradually grew apart. What remained of our connection to Egypt was an empty room, like an abandoned chalet by the red sea with no permanent residents, and which was only visited a few times of the year.

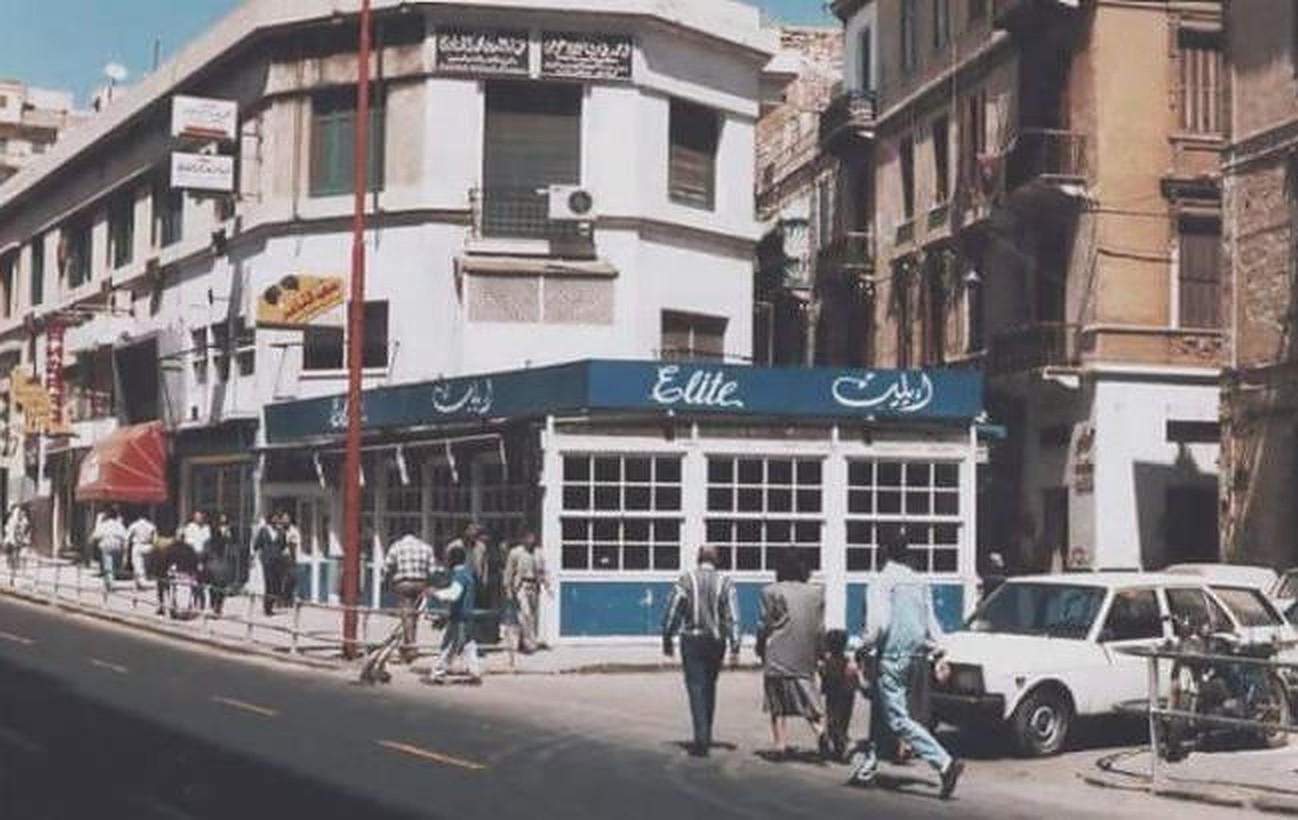

Our parents romanticized the notion of returning to the homeland as though we never left, and as though Egypt would always welcome us. But Egypt never saw us as one of her children either. Even when we walked in her streets, we would sense her uneasiness, discomfort, and unsettling attitude that is quietly hinting to us to return back to where we belong. We would see through the eyes of her own children the same feelings, and hear their silent questions of ‘Why are you here?’ or ‘Are you sure you’re Egyptian?’

I tried to prove my Egyptian-ness by serving my country. Working in politics gave me a sense of identity and purpose, and a sense that I am empowering people, particularly those that are marginalized, to connect to the world and voice their concerns and challenges. I found my passion in journalism and communications also for that reason, because I wanted to carve pathways for others to connect, just as I am equally trying to find meaningful connections.

But I cannot connect if I cannot speak their language, their emotions, and their fears. Connection involves a deeper mixture of all the senses. It is the visual, the written, the sounds, and the movement. If you cannot listen to the same sounds, speak the same words, and feel the same energies, then you will always be an outsider.

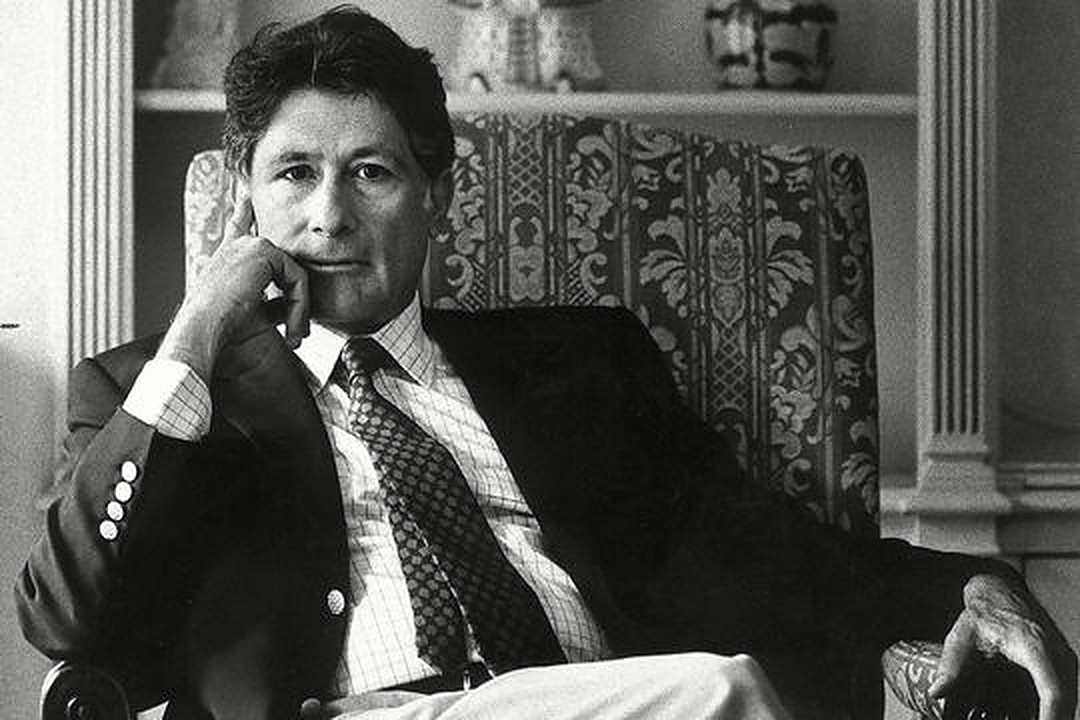

The only person that articulated what I have felt for so long is Palestinian scholar Edward Said, particularly through his memoir ‘Out of Place’. From the very beginning of his memoir, Said questions his identity and transnational existence, which pushes him into despair because of his displaced and nomadic life.

He writes, “I have retained this unsettled sense of many identities—mostly in conflict with each other—all my life, together with an acute memory of the despairing feeling that I wish we could have been all-Arab, or all-European and American, or all-Orthodox Christian, or all-Muslim, or all-Egyptian.”

He envied those who did not have to travel or wander around aimlessly, but stayed behind in the comforts of their home. He described their faces as “unshadowed by dislocation.”

At a certain point, instead of trying to search for a home, he creates an illusion for himself. He becomes attached to the nomadic lifestyle and finds comfort in his isolation. “Better to wander out of place, not to own a house, and not ever to feel too much at home anywhere,” he concludes in his memoir. He chooses to remain homeless without a concrete sense of belonging.

In a similar way, I feel somewhat the same emotions. I’ve become accustomed to being trapped inside an isolated gated community in the outskirts of Cairo and wandering aimlessly around different parts of the world. I’ve chosen to not look outside myself for a home, but slowly find it within, until the world carves a space for people like us.

Comments (0)