The night is claustrophobic, and the king lay dead in his bed. French Crusaders are a volatile threat, teetering nearer the edge of the Nile Delta. On her knees, eyes glossed over with calculation, is Shajarat al-Durr: capable, scenic, and unapologetically powerful in her constitution.

From slave to state advisor, Shajarat al-Durr was now to become the world’s first self-sustained Sultana and Egypt’s final, free-reigning Queen.

When she leaves the tent, she speaks nothing of the tragedy inside. Instead, she smiles.

“The king is well,” it was a lie that would change the fate of empires. “Now leave him to rest.”

Upbringing of A Beauty

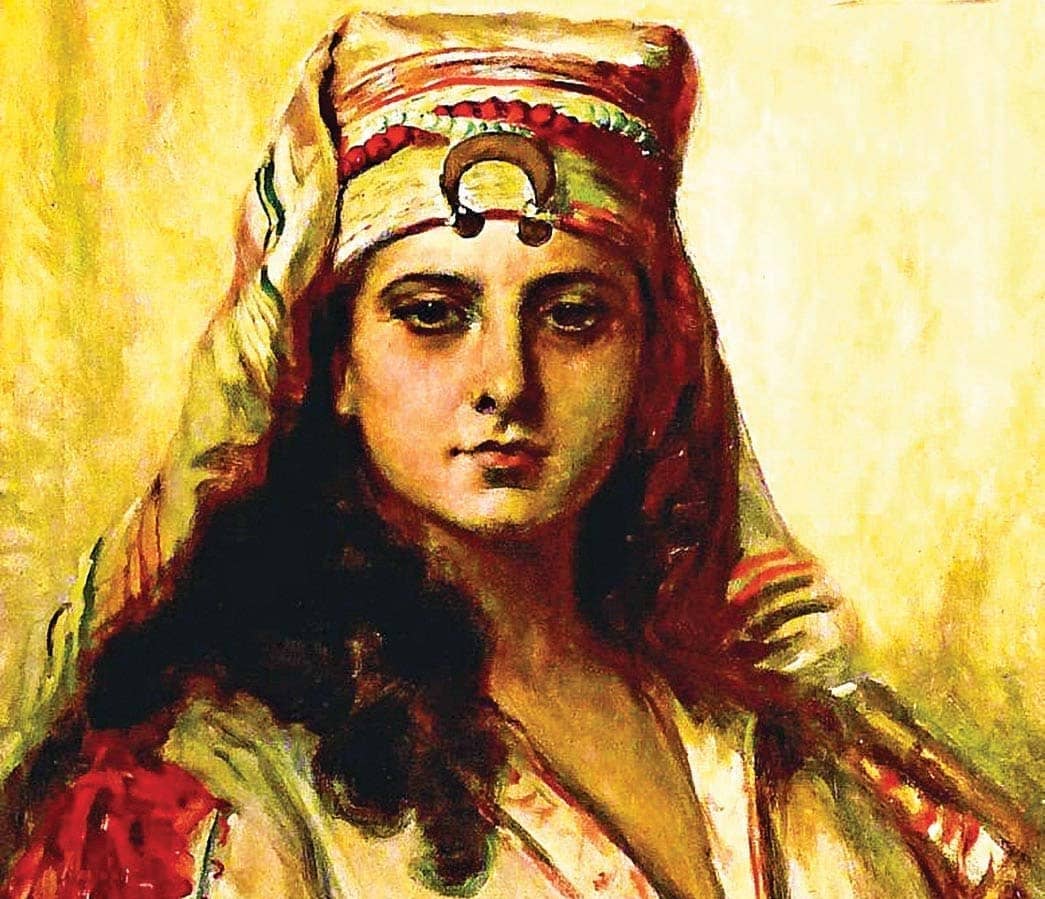

Not much is known about Shajarat al-Durr’s early life and upbringing. Her name in Arabic translates to Tree of Pearls or String of Pearls, which many have noted was a self-fulfilling prophecy: she was a thing of immense beauty, sturdy under the weight of the world. Thought to have been born in modern-day Armenia or Turkey, Shajarat al-Durr came from modest upbringings somewhere in the early 13th century CE. The first historical record of her person is dated to 1239 CE, where she had been listed as a Mamluk: a foreign slave, usually from Asia Minor, Northern and Eastern Europe, or Russia.

It is believed she resided in a harem, an area for both the women and wives of a Muslim king. Scholars boast her intelligence in equal measure to her beauty, and by 1240 CE, she was offered to al-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub—Sultan of Egypt. Najm al-Din was effectively the final member of the Ayyubid dynasty, which had come into power under the ever-famed, ever-glorified Saladin who conquered Egypt over a century prior.

It took a heartbeat, maybe two, of sweet company for Shajarat al-Durr to curry favor and ease her way from concubine to wife. Historians waxed poetic about her loyalty, describing how—upon the capture of the sultan by rival forces in 1248 CE—she accompanied him. They were imprisoned for a year, during which Shajarat al-Durr gave birth to their son Khalil.

After this unfortunate set of events, she became Najm al-Din’s favorite wife and his personal advisor.

From A King’s Deathbed to the Throne

During the throes of the Crusades, Najm al-Din was to lose his life to illness. Unlike previous attempts on the Holy Land, French King Louis IX had tapered his sights onto the Nile Delta; amongst other conquests, he planned to use Cairo as his base on the road to Jerusalem, Palestine. This was yet another chapter, or rather the final chapter, of a 150-year back and forth.

Aiding him in his final days, it was very likely that Shajarat al-Durr held power during Najm al-Din’s rule, though no accounts delineate her degree of influence. She accompanied him on the battlefield, was quick to rub shoulders with high-esteem, and was observed as his calculating, de facto right hand.

Upon Najm al-Din’s death in 1249 CE, Shajarat al-Durr and two of the king’s late advisors decided to keep the news of his passing under lock and key; the death was to remain a secret until the war was won, and the day, done. They informed the troops of his ill health, and ordered servants to bring food to his tent as usual.

The battle proceeded as planned, and under the guidance of Mamluk al-Zahir Baybars, the Egyptian army was able to offset the French. It would prove the last of the crusades, and the battle that forcibly quelled European efforts to overtake Jerusalem.

The Sultana, Fed To The Hounds

Turan Shah, the once absent son of the Sultan, posed an immense issue; upon Khalil’s untimely, young death, Turan Shah was the rightful, and only heir to the throne. However, despite Shajarat al-Durr’s immense fortitude in commanding the military, the political councils and much of state matters, she was quickly pushed into the margins as a result of her being a woman.

Though grievances were only just beginning to form. Rather than lauding those who had fought, the war-absent Turan Shah instead awarded his own men with the wealth an esteem hard-fought for by Baybars and his troops.

Together with Shajarat al-Durr, al-Zahir Baybars put together a revolt that would soon lead to the overthrow and assassination of Turan Shah.

Ascension to the throne was child’s play for the newly crowned Sultana. As widow of the king and mother of Khalil (Umm Khalil), Shajarat al-Dur assumed sovereignty of Egypt—much to the chagrin of men in power. She was considered the next legitimate heir, and the new womb of the Ayyubid crown.

Though her role, as much would’ve preferred, was not symbolic.

She was incredibly involved in the affairs of state, gilded coins in her likeness, and was part of Jumah sermons at mosques. As the first woman to ever rule over a Muslim state, Shajarat al-Durr was a point of caustic contention in the region; many loathed her inherent capacity to rule, others her steely, unwavering ambition.

As pressure mounted and became unavoidable, Shajarat al-Durr recognized that—were she not to marry—she would lose her seat. A compromise was reached in the summer of 1250 CE, when she was wed to Mamluk, now Sultan, Aybek. In his absence, which spanned war after war and nearly a decade outside of Egypt, Shajarat al-Durr was in full control of Egyptian affairs.

She ran government and council, oversaw trade. It was only upon Aybek’s return and his desire to replace her with a younger woman that Shajarat al-Durr’s story hinges on tragedy. “A man she had sacrificed so much for […] was now going to toss her aside.”

Vain, envious, and furious, Shajarat al-Durr plotted Aybek’s murder.

Successful in her endeavor, but blinded by power, Shajarat al-Durr had forged a false-belief that she would rule once more after her husband’s passing. This was not the case; his one son and heir, Ali, took over Aybek’s place—and the murder of a king was treason that could not go unanswered for.

Realizing she was a slain woman standing, Shajarat al-Durr “powdered her jewels so no one else could have them” and accepted her own arrest.

She was turned over to Aybek’s first wife and Ali’s mother, the woman she herself had been a homewrecker to, only to be beaten to death by the woman’s slaves. They used wooden shoes (aba’eeb), and the once proud and composed Sultana’s body was thrown over the side of the Cairo Citadel.

Fed to the hounds.

Today, her mausoleum can still be visited in Cairo, and the late queen was to be immortalized as “Joan of Arc of Islam.”

Comments (8)

[…] شجرة الدر: سلطانة مصر العليا […]

[…] شجرة الدر: سلطانة مصر العليا […]