In 1979, an air of melancholy, struggle, and revolution cascaded upon the city of Tehran to signal the arrival of a new class of ruler, and a new form of republic.

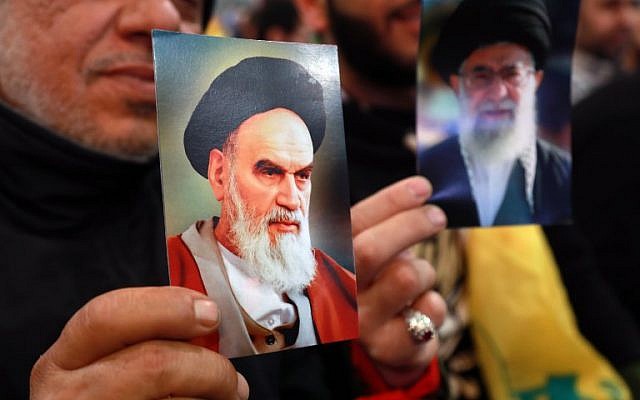

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a leading Shia cleric and Iran’s first Supreme Leader carrying the baton of revolt, proclaimed “if we want to export this revolution, we must do something so that the people themselves take government in their own hands, so that the people from the so-called third stratum come to power.”

The establishment and propagation of Iran’s Islamic Revolution sent shockwaves across the world, altering the course of regional dynamics, and shaping Middle Eastern politics for decades to come. Egypt would play a pivotal role in the opposition of the Iranian Revolution, as tensions between Cairo and Tehran continued to rise to unprecedented proportions.

Upheaval in Tehran

Fred Halliday, a prominent scholar of International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), cites this historical event as “the first revolutionary movement in modern times to be dominated by religion in this way, and to succeed in seizing power.”

Spurred on by the cataclysmic collision of tradition and modernity, the Iranian Revolution embodied the opposition of westernisation and monarchical rule.

Under the control of Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the modern state of Iran embraced radical policies influenced by the regime’s close relationship with western allies. These policies encompassed land use, civil services, taxes, and educational reforms that contributed towards the rapid urbanisation and westernisation of Iranian society. In vehement opposition to the Shah’s political and economic reforms were the Shia clergymen who had long embodied Iranian character and tradition.

Although the revolution was led by Shia clergymen, the essence of the uprising was far from being just sectarian. The revolution was protesting the tyranny and oppression that was experienced in Iranian society as the Shah further consolidated his rule.

According to John L. Esposito, a Professor of Religion and Islamic Studies at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., the Ayatollah Khomeini “has emphasized that the revolution is rooted in the common tenets of Islam and has proclaimed its relevance for all the world’s oppressed.” The revolution became a rallying cry for a downtrodden proletariat who felt disprivileged, marginalised, and suppressed under the Pahlavi dynasty.

Dreams of freedom, independence, and liberty flooded the streets of Tehran after Mohammed Reza Pahlavi fled into exile. Rapid and startling change, however, would inflict deep wounds on both Iranian society and the region as a whole. A legacy of “lashings, hangings, amputations and mass imprisonment left thousands of people dead and hundreds of thousands fleeing for their lives, never to return.”

Nothing short of revolutionary, the Islamic Republic was founded with brutish violence, a theocracy deriving inspiration and guidance from Ayatollah Khomeini himself.

Discord Among Allies

Initially, Egypt had warm relations with the Shah’s government, which peaked after the marriage of King Farouk’s sister to the then-Crown Prince Muhammad Reza Pahlavi in 1939. However, relations turned sour quickly, shifting dramatically under Iran’s new Islamic Republic.

Since Khomeini had succeeded in removing the Shah in Tehran, Egypt has viewed the Iranian government as a viable political threat. Not to mention the fear of exporting the revolution to other Muslim countries – this was a notion that Cairo could not tolerate. King Fahd of Saudi Arabia at the time called the situation in Iran “contrary to the interests of Islam, the entire Muslim world, and the stability of the Middle East” and the Saudi administration went as far as calling the new regime in Tehran “international communism.”

The conflict between Riyadh and Tehran would eventually proliferate into an intense struggle for power and influence. Today, both states have been involved heavily in interventions within regional conflicts such as Yemen, Lebanon, and Syria.

Egyptian-Iranian relations have also been characterised by similar turbulence and instability. The Sadat and Mubarak Administrations had a westward oriented foreign policy, from forming peace agreements with Israel to supporting Iraq during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, both of which ensured discord with political classes in Tehran.

Adding fuel to the fire, the Iranian government had a street in Tehran named after the ringleader of the attackers convicted of assassinating Sadat in October 1981. This marked a noticeable deterioration of bilateral relations which has not reversed since.

A strong alliance between Egypt and the Gulf states has hindered efforts at improving relations with Tehran. Cairo has been providing military support and assistance to the Coalition to Support Legitimacy in Yemen led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Surprisingly, however, Cairo and Tehran have shared interests on the issue of Syria and the Israeli nuclear program.

Egypt has vetoed, along with Russia and Iran, a UN Security Council resolution that would signal an end to strikes on Aleppo. Cairo and Tehran continue to openly support the Assad regime in Syria, despite the serious implications that might have on relations with the Gulf states and Western allies.

These geopolitical engagements prove that Cairo has no intention of seriously clashing with Iran in the near future. Currently, Egypt is far more preoccupied with the countering of radical Islam, and the possible renewed rise of the Muslim Brotherhood across the Middle East with support from Doha and Ankara.

Although the Gulf states remain fiercely opposed to Iranian foreign policies, they have slowly accepted Egypt’s mostly passive stance towards Tehran. These shifting alliances between the Gulf states and Iran is a reflection of Egypt’s strategic interests, and desire to create regional balance, and stability.

Iran’s Islamic Revolution has been a powerful instigator for change in the Middle East and North Africa. The revolution helped shift regional alliances, magnify sectarian conflict and create an increasingly polarised political environment. However, it seems like relations between Cairo and Tehran are now playing a vital role in mediating conflicts, relations that were once non-existent since the rise of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Comments (3)

[…] Exportation Through Influence: Iran’s Islamic Revolution […]

[…] التصدير من خلال النفوذ: الثورة الإسلامية الإيرانية […]