Once upon a time, Goha was headed to the market to buy a donkey. On his way, he encountered a friend.

“Where are you going?” the friend asked.

“To the market, to buy a donkey,” Goha answered.

“Say inshallah (God willing),” retorted his friend.

“Why?” asked Goha stubbornly. “The donkey is in the market and the money is in my pocket.”

When Goha arrived at the market, he found the donkey he wanted and excitedly reached into his pockets, but they were empty! All his money had been stolen!

Downcast, Goha decided to return home. On his way he meets his friend again.

“Where is the donkey?” the friend asks.

“My money was stolen, inshallah.”

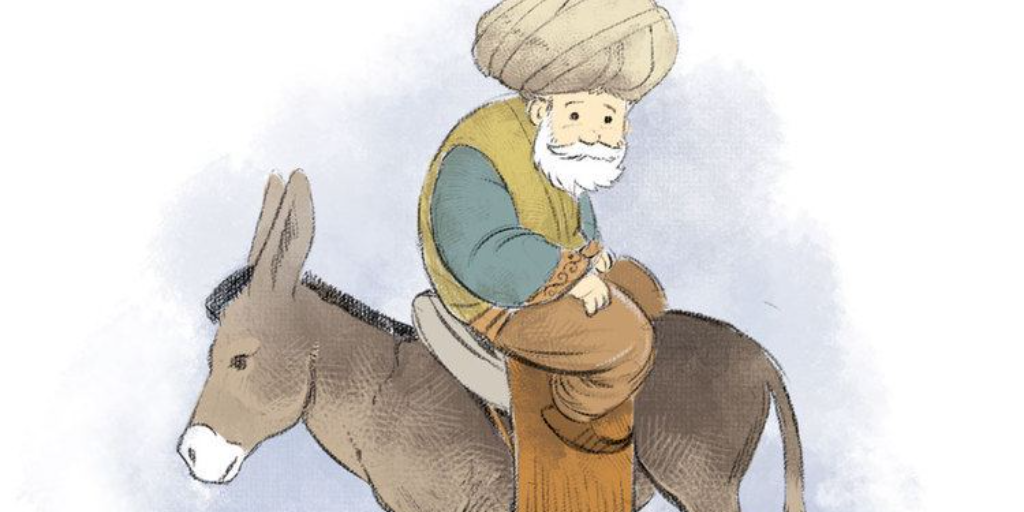

The name of Goha is one that nearly all Egyptians recognize without a second’s hesitation. He is a staple of cultural imagery and a regular guest in the local vernacular. While folk tales around the world tell of tricksters, fools, and wise men, few of them have a character quite like Goha, who manages to combine all three.

But who is this folkloric icon that has graced so many children’s stories and jokes in Egypt and what is his origin?

Goha is a character that is prevalent “among all religious, ethnic, and racial groups in the Arab culture area extending from Morocco to Iraq and from northern Syria to the middle of Sudan.” But Goha’s fame extends even further into Turkey and all the way even to the Balkans.

Given his extensive area of celebrity, there is still debate around his actual origin. According to some sources, the character we know today is based on Nasruddin Hoja, a real Turkish religious leader and satirist, whose anecdotes began to spread around Turkey in the 13th century AD.

However, the first written mention of Goha was found in an Arabic book that dates back to the ninth century AD, and it is reliably assumed that he had already been a part of Arabic oral storytelling for a long time by then. It is likely that Goha and Hoja were two separate characters that eventually merged in Middle Eastern folklore.

While there are classic stories associated with Goha, every culture adapted the character and his tales to their own traditions and circumstances. In 1951, Egyptian nationalist Ali Ahmed Bakathir took a tale about Goha fixed a nail in his previous home to reserve the right to regularly visit, and retold it to satarise his belief that Britain “used [the Suez Canal] to justify their occupation of Egypt”.

Egyptians not only infused their own wit into Goha’s old stories, they also infused Goha’s old stories into their everyday humour. For instance, someone walking narrow, winding roads is walking through beit Goha (Goha’s house, a maze), and if someone were to explain something in an unnecessarily convoluted way, they may hear the question “Wednak menein ya Goha?” (Which way to your ear, Goha?)

Though sometimes a wife or a son appear in his stories, his most recurring companion was his faithful donkey, who was always a key vehicle in transmitting the story’s moral. Goha is never portrayed as a hero or a brave man. He does not wield a sword or fight wars. In fact, there are stories where he is self-preserving almost to the point of cowardice.

But heroism was never the purpose of this timeless character. His exploits were always intended to be relatable, socially observant, and filled with teaching moments for children and adults throughout the region.

Comments (0)