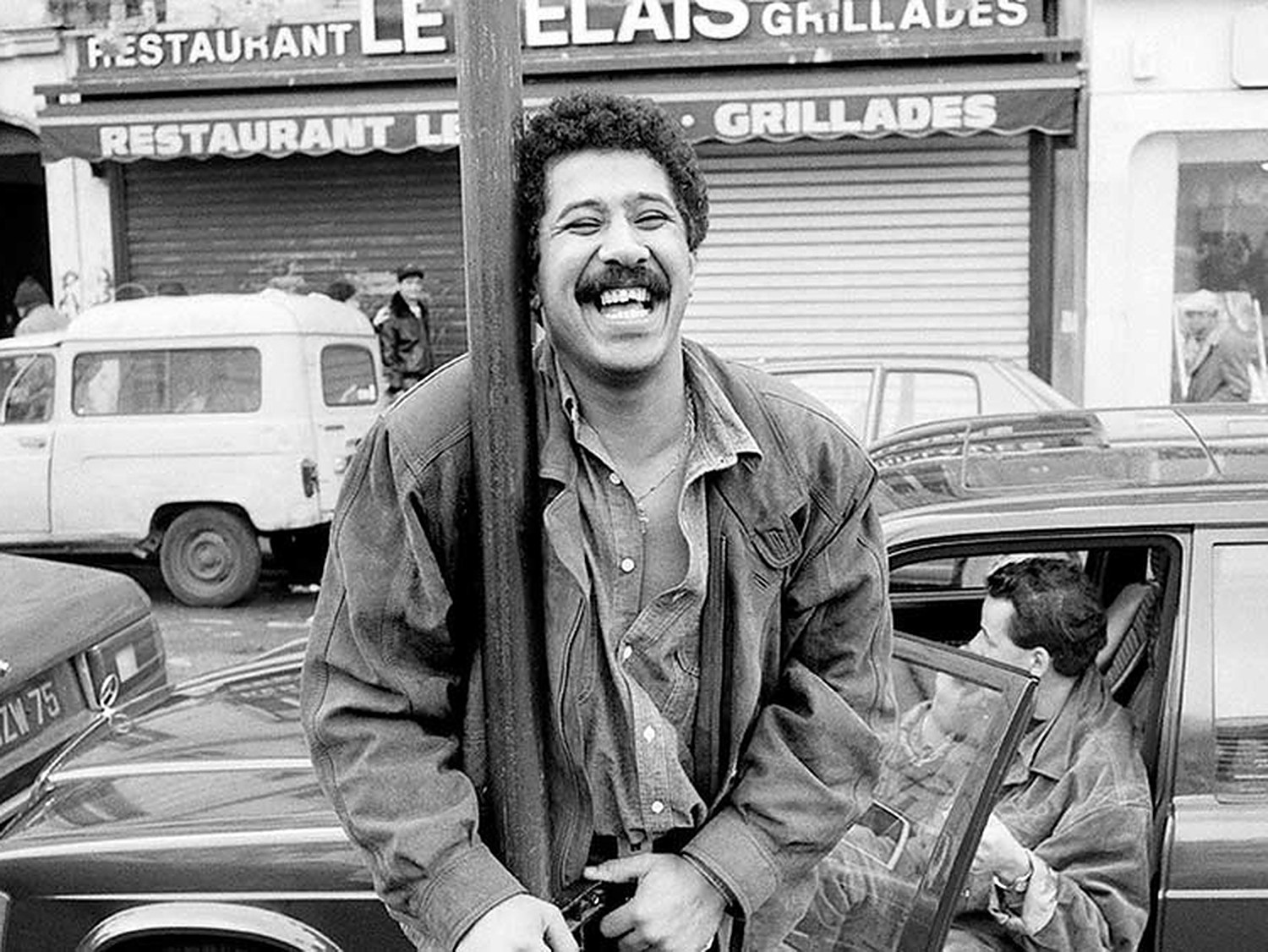

Less than five seconds after playing the song, the crowd loudly cheers and begins to repeatedly sing ‘Aicha’. Cheb Khaled, who is dressed in the same shirt worn on his ‘Nssi Nssi’ album cover, warmly smiles, and then looks out into the distance to begin singing one of the most memorable lines in music: “Comme si, je n’existais pas”.

It was 1997, and the world was still grappling with the aftermaths of post-apartheid South Africa. The voices of the anti-racist movement in Europe were growing to become much louder than ever before, and in the same year, the Treaty of Amsterdam gave the European Union a legal base on which to develop ‘appropriate measures to combat discrimination based on sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief’.

But, behind the smoke of all of these events, there were artists that inclined the ears of people’s hearts with their multicultural sounds and tunes from North Africa. ‘Aicha’ was Khaled’s first song to hit number one in France in 1996, earning him the Victoire de la Musique for the best French song of the year. The massive global success of the song did not just push Arab and Maghrebi culture into the global mainstream and create a cultural space for Arabs living in the West, but also helped build a bridge between two cultures; uncovering the merits of cultural plurality, scholar Stephen Duncombe notes.

The waves of multiculturalism were already taking place in France and Europe long before Khaled. By the late twentieth century, the state monopoly of French radio stations came to an end, and was replaced by a dozen of local private stations that totaled to be around 1,800 by 1990. Many of these newly launched radio stations were operated by and targeted France’s ethnic, racial, and religious minorities.

It first began with the creation of Radio Beur in 1981, which sparked public discourse around the merits of cultural pluralism and gave room for the political left to argue for the insertion of ethnic and racial minorities. Referring to themselves as the “invisible generation”, the operators behind Radio Beur hoped to make their unique experiences, emotions and identities more visible and heard. Affirming their existence, and building their own identity from scratch, North African youth used the power of “noise” —whether through music, speech or radio —to struggle against racism and extremism.

To create noise, and force the public to hear their own noise, was their shield and weapon, so much so that the term “Arab noise” carried its own negative connotation, as ex-president Jacques Chirac once expressed that French people are driven mad by the “noise” of foreigners and immigrants.

Yet, what is it about that ‘noise’ that was so powerful?

In Algeria during the mid-1980s, Cheb Khaled was known to open his concerts with a song about Prophet Muhammed, which was then followed by songs about drinking, women and love. This contradictory yet youthful image of a singer established the reality that racial and ethnic minorities can be “French” and “Arab” at the same time, and that they do not need to prove their Frenchness, but rather pluralize the notion of Frenchness and Arabness. That they are wholly independent of the labels and misconceptions that are thrown at them, whether liberal or religious fundamentalists. Cheb Khaled’s music and live concerts pushed the image and identity of a global citizen, who as he quotes “talks about things directly” and “speaks to the point” about issues that anyone, regardless of their background, can relate to.

While some analysts focus on the political and social contexts that helped Khaled’s music achieve global success, such as the liberal regime in Algeria and the anti-racist movement in France, this is not to say that the music of rai on its own did not have its own impact. Rai music presented a particular authenticity that won over the white European audience at the time who leaned towards the anti-racism movement. The universal nature of the lyrics were fused with oriental sounds and tunes, reimagining the way culture, nation, and race interact, and produced a rich and balanced whole that reinforced the song’s larger message.

Racist attacks against Arabs in France led to the formation of SOS-Racisme, which was an anti-racist organization that used Rai music as a force against racism and an expression of cultural diversity, organizing multicultural concerts that popularized the style of music to a much wider global audience.

Khaled’s music became a symbol of a new generation that is simultaneously Arab and modern, and global yet culturally-driven. It provided an alternative to the question: which culture should immigrants carry with them? and posed another question instead, how can we better accept the perils of cultural diversity?

Looking back, the song ‘Aicha’ today should not just carry the name and history of Cheb Khaled’s success alone, but also its legacy in opening doors for a different kind of global mainstream culture that is not solely Western, but multiethnic and diverse.

Comments (0)