In recent weeks, protests have taken place on Egypt’s Warraq Island, leading to multiple arrests. The protests erupted following moves to evict locals once more. The recent evictions have revived controversy over gentrification – increased by the government’s announcement that Warraq Island would be developed into a luxury district known as Horus Island.

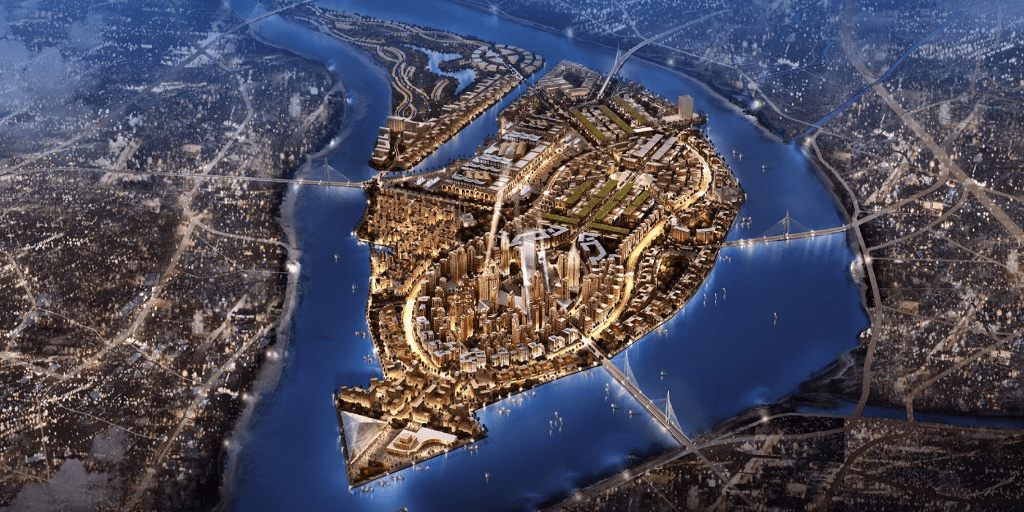

“The pictures are not of Manhattan! Can you believe they are actually the designs for Egypt’s Horus City,” published Egypt’s State Information Service, highlighting the government’s plans for seven-star hotels and commercial districts in Warraq Island, located in ِEgypt’s Giza Governorate, a few kilometers from Egypt’s opulent Zamalek island.

WHAT IS HORUS CITY?

One of the country’s ambitious megaprojects, Horus City is named after the ancient Egyptian symbol “the Eye of Horus” because of the island’s similar shape when viewed from above. Spanning 6.36 square kilometers, the project aims to transform the island of Warraq into a luxury district for commercial and residential purposes.

The development cost is projected to reach EGP 17.5 billion (USD 914.3 million). According to government studies, it is estimated that annual revenues of EGP 20.4 billion (USD 1.06 billion) will be reached over the course of 25 years following the city’s construction.

The city’s urban planning is divided into eight business districts, a commercial district and a luxury residential district. In addition, the city will include a cultural center, a central park and green spaces, two marinas, and a tourist walkway along the Nile River.

The central park, known as Horus Gardens will occupy around 620 acres, which is equivalent to almost half of the island’s total area.

The island will also feature the Horus Tower district, a keystone project surrounded by a conference hall, seven-star hotels, business complexes, and a helicopter landing pad.

Ambitious and grand in concept, the project’s most critical purpose is to ensure the removal of slums, informal settlements, and potential environmental risks to the Nile. To the residents of Warraq Island, not yet Horus to them, it is a struggle against displacement.

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM WITH WARRAQ?

Warraq is a district in the Giza Governorate that consists of Warraq Al-Arab, Al-Hatra, and Warraq Island, at a total population of 391,000. Warraq Island is home to around 100,000.

Controversies concerning the island date back to 2000, when former Prime Minister Atef Ebeid issued an order to seize the island for public use amid allegations of informal housing and environmental damage. However, Ebeid’s order was overturned in 2002 by a court rule following a legal claim by the island’s residents.

The government’s intentions to redevelop Warraq were revived in 2010, with the aim to rebrand the island to Horus City, a luxury district, and eliminate illegal housing built over the previous years. The 2011 Revolution temporarily halted Warraq’s rebranding project, eventually resuming in 2017 – a resumption mired in controversy, crackdowns, and casualties, a parallel to the ongoing evictions occurring since 15 August 2021.

Akin to the escalating eviction campaign that occurred in 2017, questions are being asked of the government over the current crackdown and the reasons behind it.

When first asked about the matter in 2017 following reports of casualties and detainment, President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi responded to citizens’ outcries in a public press conference.

“When the island is originally designated as agricultural land, and you begin to witness informal housing, the government must take action […] Do we want to progress as a state or will we continue to allow for informal planning without regulation,” Al-Sisi explained in reference to the increasing illegal construction in Warraq.

“The country was too negligent in the past, especially the past seven years. As a result, the informal development that occurred became a larger obstacle to tackle.”

WHERE WILL THE PEOPLE OF WARRAQ GO?

The government previously promised reimbursement or relocation directly to each residential household on the island during the 2017 clashes.

In 2017, responding to the government’s attempts to compensate Warraq’s inhabitants to evacuate them from the island, Warraq’s local council member Yehia Al-Maghraby claimed that residents legally own the land built on, earning their right to stay.

“The state owns a mere 62 acres of the island, and 1500 acres are the property of the residents. We would rather die than leave our land,” El-Maghraby proclaimed in 2017, shortly after a committee was formed between the authorities and residents of Warraq to reach a compromise.

Forward to 2022, and the same promises are being repeated by Egypt’s government. In a public press conference, Egypt’s Housing Minister Assem Al-Gazar affirmed that the state is reimbursing Warraq’s residents at a cost of EGP six billion (USD 313 million), with already 71 percent of the land purchased.

Al-Gazar further stressed that the island’s urbanization plans are being conducted in cooperation with the island’s inhabitants and that there are opportunities for relocation if needed.

“The government is stepping in to develop Warraq Island as part of the state’s comprehensive plan to develop dangerous areas and slums,” Al-Gazzar explained during the press conference, echoing the same sentiments from Al-Sisi’s statement in 2017.

Warraq Island’s redevelopment is one of Egypt’s many nationwide projects that aim to eliminate slums and revive urban planning. Egypt’s government identified 357 “unsafe areas” that require development. As of November 2021, 322 of the 357 have been developed according to the Urban Development Fund. Of the slums being gentrified into high-income cities, like Warraq, residents are relocated to one of Egypt’s World-Bank-funded social housing communities.

Comments (2)

[…] was not rightfully theirs. Even so, other populations who own the right to land, such as those of Al-Warraq, have still been forced to flee […]

[…] to be an agricultural island plagued by rapid informal urbanization, is being redeveloped into Horus City. Government officials hope the new city, one of many arising new cities, will become a luxury […]