What is Egyptian heritage? Depending on who you talk to, you’re probably going to get different answers.

This conversation piece draws on the responses from some of Australia’s Egyptian diaspora community captured during a weekend of focus groups held at the Chau Chak Wing Museum, Sydney (Australia) last month.

The focus groups sought to learn from Australia’s Egyptian community to see how we, at the Chau Chak Wing Museum, can be more receptive, inclusive and engaging with our collection of Egyptian heritage, and incorporate Egyptian voices and narratives.

As we have introduced in our previous article, the focus groups included 13 participants from the Egyptian-Australian community in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. They were mostly first-generation Egyptian-born migrants —some of whom have lived in Australia for decades—, as well as more recent arrivals, including students, and Australians born to one or more Egyptian parents.

While reflecting on these discussions it is essential to note that our focus groups were not representative of the broader Egyptian diaspora community in Australia, or indeed the experience of Egyptians living in Egypt, but was a first step towards bringing more voices into the Museum – something we hope to build on and seek further participation on in the future.

The discussions were facilitated by Heba Abd el Gawad with support from Alice Stevenson (both from Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage Project),Melanie Pitkin and Candace Richards,both of the Chau Chak Wing Museum, University of Sydney.

The Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage Project: integrating Egyptian voices in heritage

Since 2020, the Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage project has been using UK collections and archives to centre and amplify Egyptian voices in narrating and critiquing colonial practices surrounding collections outside Egypt. The project’s main aim has been to facilitate a dialogue and provide a platform for Egyptian feelings concerning the extraction of their heritage to foreign museums.

Similar engagements between museums and local communities too often exploit traditional knowledge, rather than build real meaningful relationships or respond to communities’ needs and expectations. These attitudes can be as violent as the initial act of extracting objects and replicates colonial modes of behaviour that museums today claim to be moving away from.

To challenge this, Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage operates in full partnership with local Egyptian partners as representative as possible of Egypt’s multivocality from the grant proposal stage onwards to ensure local needs could be identified and met.

One of the most successful initiatives was a series of comics drawing upon Egyptian humour and satire developed by local Egyptian artists and educators in Egyptian Arabic and made freely available on social media.

In UK museums, these resources were incorporated into collections databases, labels, and websites ensuring Egyptian views are there to stay.

Thus, it was critical to partner with Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage project on this initiative as it is an established and well-defined model which we hope to take further and implement at the Chau Chak Wing Museum.

Welcoming Egyptian Human Remains: the Welcome to Country Ceremony

Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage was a collaborator facilitating co-framing this dialogue between the Egyptian-Australian community and the Chau Chak Wing Museum, the project entered a new territory moving geographically and intellectually from Europe and Egypt to Australia.

This was an exciting yet daunting prospect for the team, given that Australia also struggles with its complex colonial history and its ongoing relationships with First Nations communities. While Australia’s attempt to heal rifts with First Nations people can offer lessons on how Egyptian communities’ rights could be recognised in museums, within Australian museums migrant communities remain marginalised as First Nations communities’ representation is, rightly, prioritised.

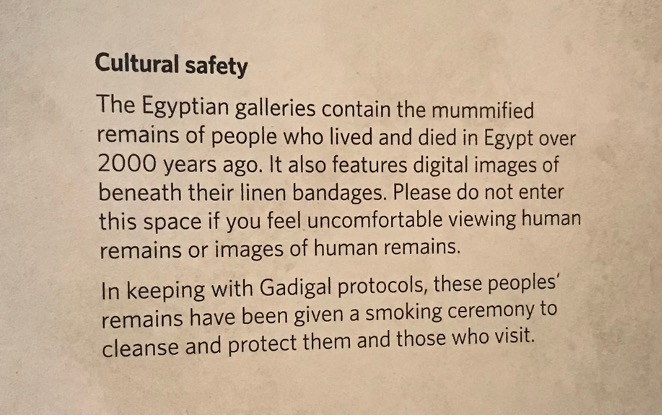

An example of the complexity is the cultural safety sign at the entrance of the Egyptian galleries informing visitors that a smoking ceremony has been conducted following Gadigal protocols in the presence of Egyptian human remains. This was part of a Welcome to Country performed by an Elder of the traditional owners of the land on which the Museum is built – the Gadigal lands of the Eora Nation.

The Welcome to Country is a ceremony performed across Australia today that is conducted by a member of that community to pay respect to the traditional owners and welcome outsiders into that country.

When performed for the human remains held by the Museum, including people from the ancient regions of modern-day Egypt, Jordan and Cyprus, it was a way of welcoming these individuals from faraway places, acknowledged to be taken without their consent several thousands of years after their deaths, to what is now their resting place.

It is worth noting that no members of the Egyptian community were consulted prior to these rituals. And, while at the core of this act is respect, it begs the question of respect to who? And by whose standards?

Such complexities coupled with the long and deeply rooted colonial injustices marginalising Egyptian communities means that attempts to initiate Egyptian-Australian dialogues need to be radically and sensitively transparent in its motivations. Who is this for? Is this to further the Museum’s decolonising agenda or to meaningfully serve and build relationships with Egyptian communities?

Realistic responses to these questions can only be sought through active honest reflections between communities and the museum where both parties can openly lay their needs and expectations. The Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage project saw its role with the focus groups, as both observing and reflecting on how the wider Egyptian community could be centred.

Whose heritage is Egyptian heritage?

The topics discussed by the focus groups over the two-days included: ‘What is Egyptian heritage?’, ‘Who owns Egyptian heritage?’, ‘How do you define yourself in relation to Egyptian heritage?’, ‘How can museums (with particular focus on the Chau Chak Wing Museum) re-think its displays and tell different narratives?’ and ‘What kind of community engagement and public events would you like to see in a museum setting?’

This was preceded by the opportunity for participants to introduce themselves and share a little about their personal stories, hear a short presentation on the history of Egypt in Australia and the way Egypt has been collected and historically displayed at the Chau Chak Wing Museum.

A key sentiment which emerged from the discussions was the recognition that Egyptians have felt, and continue to feel, excluded from narratives and representations of their past – a feeling entrenched in years of power struggles via foreign occupation, colonialism and Eurocentrism which has long been at the heart of the discipline of Egyptology itself.

Another overarching sentiment was the multiplicity of experiences shared by the participants who regularly negotiate their Egyptian heritage and values in an Australian context. “Australia is my life, Egypt is my roots,” said one participant, “I belong to both”.

Another participant noted ‘To be Egyptian is to speak the language, to know a place and to assert your place to others’. But, for future generations born in Australia to parents and grandparents of Egyptian descent, this identity becomes more and more problematic and diluted.

Within an Australian context, this feeling of exclusion is perhaps accentuated by the fact that the diaspora community is quite spread out. The collections of Egyptian heritage are similarly dispersed. For the most part, they have remained relatively static within the nation’s large collecting institutions.

These can be exclusionary spaces behind imposing museum and gallery facades, or part of University museums, where displays are often difficult to find within a campus, and may be limited in access to staff and students, or by appointment to those already in the know, or held in storage.

A key discussion within the group acknowledged that a significant barrier to identification within the context of Egyptian heritage in museums is the over-representation of Pharaonic Egypt with little to no engagement with Egyptian culture after that. ‘Where is the present, contemporary life?’ was a question that kept coming up.

In exploring the current displays at the Chau Chak Wing Museum, and museum exhibitions more broadly, several participants observed, ‘There is no sense of modern Egypt and no linking to ancient cultural heritage’, ‘Where are the people?’, ‘We should have more focus on living culture, and make it modern people-centered’, ‘People should feel part of the story’ and ‘We need to demonstrate a continuity of Egyptian culture and we should do this through the telling of Egyptian people’.

Not only was this focus on Pharaonic Egypt deemed by the group to be a barrier for Egyptian people’s connection to their own heritage, but it was clearly identified as having implications for how museum audiences of other cultural backgrounds engage with and form lasting impressions of Egypt as well.

Of course, museum exhibitions are primarily driven by the strengths of their collection.

At the Chau Chak Wing Museum, for example, there are very few examples of Egyptian cultural heritage post the late Roman – early Coptic era, due to the Nicholson Collection’s purpose as an antiquities collection and collection guidelines that limit what acquisitions have been sought for other areas, such as art and ethnography.

But, of course, experiences can be layered through means other than just the physical objects – labelling, graphics, audio visual guides, public programming, and so on. And it is in this space that museums can be doing more work to engage Egyptian voices to develop new ways of thinking and addressing how Egyptian people want Egyptian culture to be perceived in museum contexts both for themselves and the museum’s broader audiences.

Another observation formed among the focus group participants is that traditional Egyptian knowledge is lost when interpreted within a Eurocentric framework, and that infusing modern-day Egypt and the Egyptian way of life can greatly enhance the narratives and lens through which we see and understand ancient Egypt.

A museum label named ‘Egyptomania’ at the CCWM excluded the development of Egyptology from the local Egyptians’ point of view, nor did it mention how Egyptians participated in creating it.

Egyptians were only mentioned in relation to selling their heritage to foreigners in a context and a place where you, as a visitor, should or at least be encouraged to respect the heritage of yours and others. The label was a reminder of a scholar who mocked King Ramses II because the King mentioned his horses and butlers in war records while not mentioning his military leaders! Simply ask an Egyptian why Ramses II did that, and they will tell you why, even without an Egyptology degree.

But how can the Chau Chak Wing Museum learn from the obstacles identified by the focus group participants which hinder those crucial feelings of connection, inclusion and belonging (only some of which have been highlighted here)? For example, how can the Museum enhance its collections in meaningful ways with intangible heritage traditions? More inclusive and neutral language? And the delicate cross-cultural sensitivities between the traditional practices of Australia’s First Nations and modern-day Egypt?

While the Museum continues to work with the diaspora communities here in Australia, we are interested to hear your ideas and opinions on this topic. One of the aims of this initiative is to create a new repository of stories and personal reflections on objects in the Chau Chak Wing Museum’s collection which may help re-frame how our daily visitors here in Sydney, think about ancient and modern Egyptian culture. This repository is currently an imagined space, but we envisage that it will include your stories, artistic impressions, creating a Tik-Tok, or sharing photography – whatever is meaningful to you.

If you want to contribute to the discussion, and find out more about how to be involved, please email: [email protected] to join the project’s mailing list.

This is the second part of a monthly public conversation series published on Egyptian Streets co-written by community participants from Australia’s Egyptian diaspora, Dr Heba Abd el Gawad and A/Professor Alice Stevenson of Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage Project, Dr Melanie Pitkin and Candace Richards of the Chau Chak Wing Museum, and other internal and external collaborators. This initiative aims to critically explore and engage the Chau Chak Wing Museum’s collection on a diverse range of topics guided by the needs and expectations of the Egyptians around the world, to help inform a new mode of museum practice, engagement and display at the Museum.

The authors would also like to thank Sara Hany Abed for her invaluable comments on this article.

Comments (4)

[…] friends and acquaintances of all age groups, including some of the participants in the Museum’s focus groups, and it is interesting to hear their […]

[…] noted in a former article in this series, the museum includes a cultural safety warning sign for visitors at the entrance to the Egyptian […]