By Emma Pearson and Katie Welsford, contributors, EgyptianStreets.com

“I found Rome a city of brick, and left it a city of marble.” Whether or not the emperor Augustus actually spoke these words, he certainly knew the value of controlling public space and the cultural landscape. His massive building projects transformed Rome in the course of a generation. His poets fashioned myth that pointed to him as the pinnacle of history. Images of victory, piety and familial stability saturated the lives of his subjects.

Throughout history ruling parties have sought to influence their people in a similar fashion. While each circumstance is distinct, those who have achieved power generally recognise that public space and public memory are key to them keeping it. Today in Egypt, stability is the byword of the military led government, which has set about cementing its interpretation of recent history in monuments and attempting to shore up its monopoly on public memory.

Monuments as narratives

Egypt’s pro-military government has been busy. In Tahrir Square, the much discussed monument commemorating martyrs from the past two and a half years was opened in November whilst in October, Rabaa al-Adawiyya – the site which saw an estimated 1,100 killed this summer, received its own gift from the regime: a minimalist style sculpture of two arms (representing the army and the police) protecting an orb (the people).

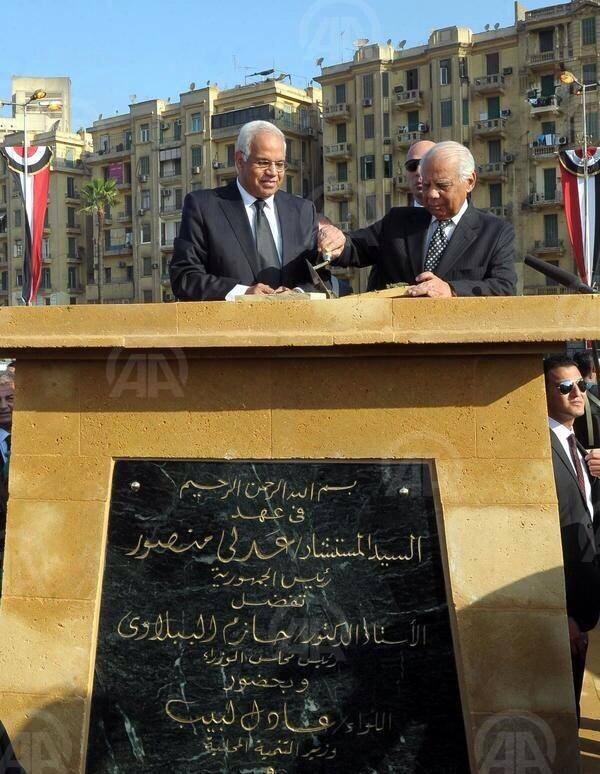

Both monuments are, unsurprisingly, controversial. Attacked, graffitied and reduced to rubble within 24 hours of its opening, Tahrir’s memorial was viewed as bitter evidence of a military unwilling to hold accountable those responsible for killing protestors. Added to the fact that the monument’s plaque bore just the names of ministers who unveiled it, rather than martyrs’ names themselves, it is not surprising that the construction enflamed frustrations in the way that it did.

But these monuments are more than just controversial. They are worrying evidence that the regime is attempting to control Egyptian’s memories of the past in order to alter conceptions in the present. Statues and memorials exist, after all, not just to remember history, but to project a specific narrative onto the present and into the future.

The Rabaa al-Adawiyya sculpture, erected following an extensive clean-up operation of the area, does not even attempt to commemorate the 1,100 lives lost this past August. It is instead a concrete reiteration of al-Sisi’s July mandate to crack down on “terrorism” – or in other words, that which threatens the ‘stability’ of the state. It is a statement of gratefulness to the army and police for ‘saving’ the nation, and a sturdy reminder that the military feels wholly justified for its actions this summer: actions for the greater good, one might say.

In the case of the Tahrir memorial meanwhile, it is as much an attempt by the state to reclaim the space of Tahrir as it is a statement that ‘the time for revolution is over’. The end point has been reached, it says, and now is the time for clean-up and commemoration. Anyone who now loses their life in the ongoing turbulence over Egypt’s political identity cannot be defined as a martyr for the revolution. The revolution is gone, and the military are the rightful, legal ‘victors’.

Forcing amnesia

America seems to be feeding this notion of the military as the revolution’s victors. John Kerry’s recent statement that the revolution was ‘stolen’ by the Brotherhood, and that Morsi’s ouster is all part of the path towards democracy was lapped up by the new Egyptian government. For many Egyptians, however, this narrative sits ill with their memories of this summer’s bloodshed.

Perhaps the military assumed that amnesia would come naturally. After all, many analysts commented in July on the oddly amnesiac state of Egyptians upon Morsi’s ouster, as many who had previously battled against SCAF rule greeted al-Sisi with open arms.

But the military severely underestimated Egyptian resilience and refusal to give up its past. This year’s anniversary protests for the Mohammed Mahmoud clashes saw protestors chanting “remember, never forget!”, whilst the graffiti outside Cairo’s old AUC campus , which serves as a constant reminder of past injustices, is fiercely protected.

The pro-military regime is subsequently having to go further than simply using monuments in attempting to alter remembrance of the past. As Egyptians fiercely hold on to their memories, the new government is attempting to prevent any form of commemoration for those who lost their lives this summer – a further attempt to ensure the new state’s ‘purity’ and ‘cleanliness’. The arrest of two Egyptian sportsmen in recent weeks, both disciplined for displaying variants of the pro-Morsi four-fingered sign, as well as the arrest and 11 year imprisonment of 21 young women – several under the age of 18 – is clear evidence that in Egypt today, remembrance is subversive.

“An untidy melee of remembrances and hopes

With a regime attempting to control a nation’s collective memory in a bid to establish itself as supreme, it is difficult to digest Kerry’s statement regarding the true path of democracy. Not only are his comments risible given the clampdown on personal freedoms within the country – the new protest law just one amongst several instances of the state clenching its muscles – but his comments completely mask the fact that Egyptians are being subjected to a forceful forgetting. A forced amnesia.

For Egypt to move forwards, a crucial step must be made regarding conceptions of the past. Attempts to wipe out memories cannot be made. Countries are at their most free when able to look critically at their past, the good and the bad. This may mean that diverse points of view may abound – but this is as it should be. Democracy is, after all, about multiple memories. A cityscape should be an untidy melee of remembrances and hopes – not a canvas for those in power.

Emma Pearson and Katie Welsford have previously written for The Majalla, openDemcracy, Asfar Journal, The Palestine-Israel Journal and The Forum for the Discussion of Israel and Palestine.

Comments (18)

Interesting article, valid observations. Visiting the area last month I noticed that the gardens planted in Tahrir in October (curious point: reclaim space by planting a garden!) contained a good many potted plants. The psychology interested me – pots are by definition temporary and moveable. I sensed an odd air of impermanence. Does anybody yet really know what to do with Tahrir?

Great point about the graffiti: further down Mohammed Mahmoud Street last month there was one of Tawfig Al-Hakim, and a reference to his novel “The Return of the Spirit.” I am now re-reading his play “The Sultan’s Dilemma” – essential reading just now, you could say.

[…] published on EgyptianStreets.com. Co-author: Katie […]