In a recent editorial published in The Age, former Australian Minister Peter Reith called on Australians to boycott Egypt. This boycott, he suggested, should not only consist of avoiding travel to the country that has gone through four Presidents in four years, but also stopping any funding of development projects in the country.

Both of these ideas are a mistake and Australia should have a greater vision in mind. Here is why.

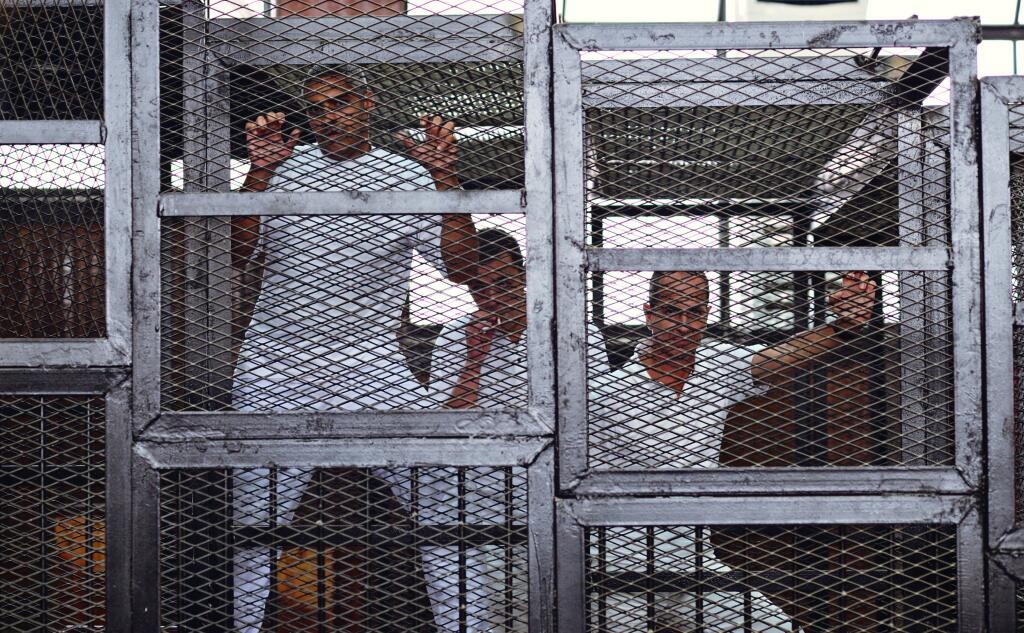

As an Egyptian and a “journalist,” I wholeheartedly condemn the sentencing of journalists to prison simply for facilitating the crucial role of journalism: that is, acting as a check on society and those in power.

This imprisonment, including the recent trend of isolating voices of dissent in Egypt, is a worrying trend and signals that the road to democracy after the January 25th 2011 revolution is much longer than many had expected.

The question is: who is responsible? Are the four million tourism workers, who leave their homes and families in order to make enough of a living to feed their children, to blame?

While a major source of income for the country is the tourism industry, the government will not hesitate to explore other avenues. Any ‘boycott’ by Australians can easily be covered by the 23 billion dollars of investments pledged by Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries.

Instead, a boycott in Egypt merely hurts the father or mother who spend all their money on educating their children. Approximately 60 percent of Egyptians live in poverty, with 25 percent living below the poverty line. Cutting off the primary source of income for these Egyptians, many of whom work in the tourism industry, will not encourage the government to bring Peter Greste home: it would simply punish the average Egyptian.

It impacts foreign hotels and businesses which not only employ these everyday Egyptians, but also Australians, Americans, Germans and more. Meanwhile, the encouragement to ‘boycott’ funding the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development will largely impact the people and businesses that allow the fostering of a community that holds democratic ideals highly and that will forever remember the assistance received from Australia and other countries.

Moreover, a boycott of travel to Egypt is all but effective. At its height before the 2011 revolution, the total number of Australians that visited Egypt was 110,000 (of which many were Egyptian-Australians). Today, with tourism at an all-time low in Egypt, that number is but a dream.

More importantly, a boycott of Egypt would severely impact Australia’s interests in the region. With wealthy countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Jordan and more strongly supporting and defending Egypt, a public move by the Australian government and people to boycott Egypt would threaten diplomatic and economic ties between Australia and those respective countries.

Finally, it is crucial to remember that the verdict the three Al-Jazeera journalists received is not final. While Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi promised not to interfere in the judiciary’s affairs, Peter Greste and his colleagues are still able to appeal their sentencing at a higher court. Therefore, a boycott would prematurely impact Australian ties with Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries and it would assist in the elimination of a lifeline for many average Egyptians.

So, who does a boycott not help? Peter Greste and the two other Al-Jazeera journalists.

Here is, however, how Australia can help bring Peter Greste back to his parents and siblings. Australia’s Prime Minister can exert greater efforts to communicate with the Egyptian leadership. Australia can call on the Human Rights Committee to investigate Egypt’s continued silencing of dissent. Australia can use its position in the Security Council to lobby greater international support for the release of Peter Greste and all jailed journalists.

Perhaps even, Australia should explore ways to support those championing for social change in Egypt. Unlike Peter Reith’s claims that “Egyptians could not give a damn about anything we say,” representatives of the government, and even Australian tourists, should travel to Egypt and unravel the hunger of Egyptians for social change. Australians should speak to the simple Egyptian to learn of the population’s true and deep-rooted problems. Australia should work to help those everyday people – and the young passionate Egyptians that have on tirelessly risked their lives for change – achieve their dreams. One lower court’s verdict should not decide how a whole population is treated.

Boycotting Egypt does nothing but potentially harm the lives of simple Egyptians who have probably never heard of Peter Greste.

Comments (7)

I live in Egypt in a very local and low income area calle Shoubra. Whenever a local hears that Im Australian they are constantly asking questions about how can Egypt become a better country. When they see me keeping my rubbish they say I wish all Egyptians were like that.

We can not condem Egypt for not being perfect. Australia is falling further and further away from that title every day. The average Egyptian is so passionate about improving their country. These things take time. The Muslim Brotherhood are taking responsibilty for bombing and deaths all over the country. There is fear amongst all Egyptian. Sending my husband to work every morning is concerning. I dont agree with the verdict, but I can understand how they may have overreacted out of fear. Give these people a chance becuase they do listen and they do care. They just have a lot more on their plates than the average Australian.

Talking to Egyptians has never been the answer. They don’t listen, only pretend to listen, then do the opposite.

How can a judicial system work properly if the evidence is only heard on appeal, after being found guilty by crony judges who themselves fear consequences?