Throughout history, art was a platform for people to express themselves away from the constraints of language. Graffiti art, in particular, was an outlet for the impoverished, the marginalized, and the oppressed, to voice out their concerns away from governmental restrictions and decorum.

Under Hosni Mubarak’s regime, the Egyptian people went through a number of traumatic experiences that marginalized their humanity and altered their consciousness as a whole. Police’s excessive use of force, imprisonment of opposition leaders, electoral fraud, limited freedom of speech, excruciating destitution, and rise of sexual harassment, were some of the events that impinged the Egyptian consciousness. These constant infringements on their basic rights by the state, however, helped provoke a sense of collective identity among the people.

First observed in January 25th Revolution, this shared identity was also palpable in the emerging graffiti art at the time. After the revolution, graffiti became more prevalent among Egyptian walls and mirrored the alterations in the political scene. With Mubarak’s downfall, the volatility of the political stage and the rise of political partisanship were directly reflected in the changing themes of Egyptian graffiti.

Revolutionary Period [2011-2012]

The astounding success of the revolution in overthrowing a 30-year-old dictatorship in just eighteen days gave the people a sense of empowerment and optimism. Most of the graffiti and murals painted during the first two years drew on the hopes of a better future and vowed to fight political corruption in Egypt. Images of Muhammad Hussein Tantawy, head of the Supreme Council of Armed Forces [SCAF] and Mubarak, were commonly painted with phrases of indictment along the walls.

Attempting to break through governmental limitations and constraints, albeit symbolically, was another theme of the artworks done after the revolution. This could be seen in the 2012, No Walls movement.

The No Walls movement came into light as a response to the government-installed concrete barriers. The barriers, built along Mohamed Mahmoud Street, were an attempt by the SCAF to block the youth’s freedom of assembly and limit their mobility. The youth, however, exploited the opportunity and turned the concrete into a new outlet of expression that further amplified and publicized their voices. Besides the No Walls movement, another graffiti artist, named El-Zeft, also attempted to challenge the purpose of concrete barriers. In El-Zeft’s Tomorrow artwork, the artist painted an image that envisioned a better future for Egypt.

The youth were adamant about changing their reality and this was seen in the types of graffiti artwork and mural paintings that dominated the street art scene throughout 2011 and 2012. The prevalence of these themes, however, came to a halt with the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood [MB] into power mid-2012.

Muslim Brotherhood Rule [2012-2013]

Soon after the MB was inducted into power through an elected president and a majority in the parliament, radical political polarization started to sweep the country. The collective identity that was once shared by the Egyptians slowly broke down as the mainstream media, with their full-fledged fear mongering, started a series of speculations that impugned the MB’s political legitimacy.

The Egyptians grew distrustful of the reigning regime: Are extremists really flooding into the country? Is Morsi forging deals to give up Sinai and the Pyramids of Giza? Did Morsi just give up Halayib and Shalateen to Sudan? On the other hand, there rose pro-MB media outlets that exhibited a strong, religious tone and regularly condemned the media, seculars, and revolutionaries for not supporting Morsi.

From 2012 to 2013, the year during which the MB ruled, graffiti art reflected the rising political partisanship. Walls were split between one campaign painting derogatory slogans aimed at the Brotherhood’s leadership, while the other campaign responding back by either censoring these paintings or painting phrases in support of the MB. The ongoing feud between the MB and the mainstream media distracted the youth, which ultimately sidelined their hopes and ambitions of a better future.

El-Sisi’s Rise to Power [2013-Present]

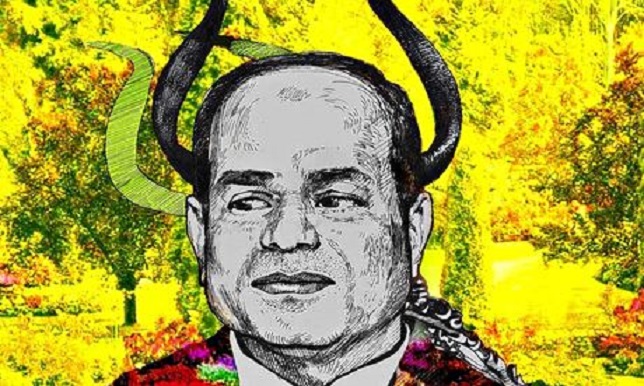

The political partisanship that peaked in 2013 took a twist in 2014 when the former Minister of Defense, Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, assumed the Egyptian presidency. His ascension to office was guided by the undivided support of the mainstream media.

Fear mongering reached new heights in the country. Opposition became synonymous with treason, disloyalty, and terrorism. Bassem Youssef, one of the most popular satirist in the Arab world, was forced to stop airing his weekly program. Other TV hosts and public figures, such as Yousry Fouda, Alaa El-Aswany, and Dina Abdelrahman, also fell out of favor with the autocratic regime and were forced out of the media’s sphere. The youths, on the other hand, were labeled as “traitors” as they allegedly attempted to ‘disrupt’ the Egyptian fabric through protests. These excisions signaled the country’s new direction; there was no room for any opposing or critical views.

![On top, a spray-painted slogan saying, “Bashar [Syrian President] = C.C [Egyptian President].” On the bottom side of the concrete is an opposing spray-painted phrase stating, “Morsi is my president.” (Photo credit: Reuters-Amr Abdullah Dalsh)](https://egyptianstreets.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/7.jpg)

Four years after the revolution, countless Egyptian activists are in prison, while Mubarak and his cronies are gradually being exculpated from all charges of corruption. Consequentially, the state of Egyptian graffiti is at an all-time low. Walls that once hosted paintings envisioning a better future for Egypt are now exclusive to the strife between the pro-Sisi and the pro-MB campaigns. In 2015, the Egyptian youth who expressed their desire for a better tomorrow and vowed to fight political corruption are silent spectators of an acrimonious reality.

Editing by Marina Kilada and Enas El Masry

Comments (2)

[…] egyptianstreets.com Graffiti article egyptianstreets.com article on homophobia […]

Most useful in understanding Egypt.