There is no doubt that the past five years have dramatically changed the lives of Syrians; this time has also changed how they see themselves in a milieu that is, according to many of them, quite different from the homeland. In fact, not all families fled the war-ravaged Syria concurrently; each family and individual’s reasons differ but it all comes down to the moment of coming face-to-face with death. Life is harsh when innocents have to leave, and tiring in their attempts to readapt.

With the diaspora of the Syrian people, women are facing sociological and psychological conflicts as widows, displaced, and refugees. According to the latest figures from the United Nation’s Refugee Agency, 21.2 percent of Turkey’s 2.7 million registered Syrian refugees are women aged between 18-59. Some are placed in border camps and get intermittent humanitarian aid from NGOs, while others look luckier for being able to settle in towns with alleged better conditions.

For refugees, it’s not easy to get a job in Turkey, even with a university degree and years of experience. Turkey enacted new legislation to regulate refugees’ labor conditions, but still lacks realistic access to work legally.

Besides being known as skilled, they also proved that they can be responsible and share family burdens in exile. From home-cooked food to handmade crafts and event planning, formerly employed Syrian housewives tried to find themselves again by integrating into Turkish society, securing a source of income and investing in their leisure time.

In Turkey’s southeastern border town of Gaziantep, a modest handmade crafts bazaar was held as the first of its kind in the town, with twelve Syrian housewives enthusiastically participating to showcase their products.

“[Although] I don’t know all of them, I didn’t face any difficulties to gather them, they were on standby for my call,” said Dina, one of the bazaar organizers. “I’ve had to apologize to eight more women as space isn’t enough. Over 250 guests came and bought stuff yesterday. All this made us decide to reorganize another event in a bigger place so more women can participate.”

The bazaar’s venue is a kindergarten run by Dina’s partner, Reem, who chose her place due to the very limited budget of the event. “Although the participation fee to rent a table is 75 Turkish lira (USD 25.6) which isn’t that much, but still many women can’t afford to pay it,” said Reem. “If the event is financially supported we would definitely have hosted more.”

I met some participants at the bazaar who openly spoke from the heart.

Dina: “Any project needs capital, and we the Syrians can’t risk a lot of money in a foreign country, but with little money you can show the people how your work is fantastic. Many girls and women do amazing stuff at home but they don’t dare to take a step forward establishing a business. I helped a girl to show herself to the Syrian community here – I even made business cards for her.”

Amany: “I’m a pharmacy graduate, I had a pharmacy in Aleppo. I came to Antep four years ago, wanted to work as a pharmacist but no one allowed me to, so I thought of my minor profession in Syria. Our financial status in Aleppo was better. I would show my customers my handmade mattresses and dresses, I would sell on a larger scale. A month ago, I opened a small shop for makeup and wedding accessories [and] my mom helps me. I have Turkish customers and they adore my work.”

Raneem: “I recently attended a course on making cakes and desserts, after that I did something that amazed my relatives, I couldn’t imagine that it’s going to work. Qet’aat Hob (A Piece of Love) is the name of my kitchen. I like the meaning in Arabic; I also believe that doing something from your heart makes it prettier. We, the women of Aleppo, always feel the pride of our cuisine. I wish to have my own cakes shop and to have Turks buying my products.”

Raghad: “I recycle and decorate used glass bottles and cardboard to vases [and] I also work with etamin (cross stitch). I brought many of my work in Syria with me. When the war erupted, there weren’t raw materials like yarns, even here, I face difficulties to find materials, I buy from Ankara and it’s too expensive for me. Working with etamin is hard, expensive and time-consuming, It’s originally a Turkish craft not Syrian, but I like it.”

Dina: “This wasn’t my profession in Syria, but I’ve had the passion for it since ages, it was a hobby and I worked it well for me and my relatives before. I’ve been here for 3 years, I see when Syrians have a wedding party or any occasion they get lost in what to do and from where to buy their stuff; the language barrier is another problem. A month and a half ago I decided to turn the old event planning hobby to a profession and show that to people. Next month I have a client, an opening of electronics shop.”

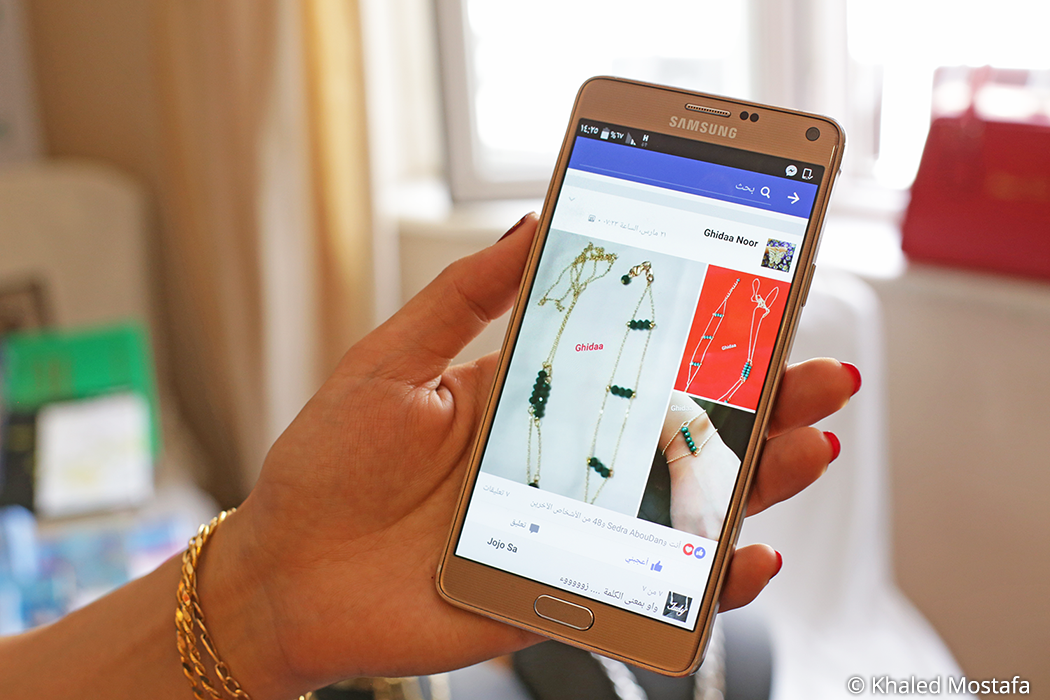

Ghidaa: “I came here a year ago. In Damascus, I was an administrative officer and all that was like a pastime activity that I decided to take seriously just four months ago. I work from home, no ability to start a business at all, but I wish one day to have my own custom jewelry business. You know, to tell me that you like a piece of my jewelry means a lot to me than just buying it. I have 1,000 fans on my Facebook page, I share my work with them. When a girl wants to buy my stuff we meet in front of Sanko Mall, everyone knows it. I still can’t count on this as a real source of income; sometimes I don’t sell anything for 10 days.”

Bushra and Hala: “We lived in Sanaa, Yemen for 18 years and came [to Turkey] last year when the war broke out there. We’re very interested in home-cooked food, our friends encouraged us saying we cook pretty delicious food. There is a barrier between women and the market, and now we’ve got free time that we didn’t feel before in Syria. Also, the living expenses are getting expensive here by the time, the thing that makes us sometimes feel the need to work and do something.”

Comments (0)