I could feel their heavy-eyed stares whether I was entering my hotel in Sharm El-Sheikh, walking along the leafy streets of Maadi, or sitting in an air-conditioned metro cart in Cairo.

“You’re not Egyptian!” almost every security guard or hotel staff member would comment.

“Are you really Egyptian? Both parents? Where are you from?” random Egyptians would quip whenever I was in public.

“No way! You’re lying!” would often be the response no matter what I said, even if it was in perfect ‘Egyptian Arabic’.

As an Egyptian living abroad, visiting Egypt recently reminded me of what it was like growing up in the country.

At sporting clubs, random people would come up to me and speak to me in English, fascinated that a “foreigner” was there. Amazement, then disappointment, would run across their face as I started speaking Arabic, explaining that I was in fact Egyptian.

At tourist sites – ranging from the mosques that are dotted along the historic Khan El-Khalili market to the Pyramids and the Egyptian Museum – security and staff would demand to see my national identity card or my passport to ‘prove’ I was Egyptian (and therefore my purchased ‘Egyptian tourist’ ticket was valid) and would nevertheless continue questioning me afterwards.

At malls, I could see young girls giggling and taking photos at the palely complexioned man. On the metro recently, I could feel the men stare, wondering what a crazy foreigner I am to ride the metro.

It made me wonder what it is like to be a woman, particularly a foreign woman, in Egypt. If I could feel the stares of men, if I felt uncomfortable walking along the streets, then what did women feel?

“It’s an everyday thing,” said one female friend about the daily harassment, verbal or otherwise, she experiences in Egypt.

“You just get used to it and eventually you don’t react as much and start to block it out”. These words spoke true – when I lived in Egypt, after some time, I just started to ignore the comments and the stares.

However, if during one of the many interrogations I was subjected to, I ever mentioned that I lived abroad, I’d immediately be dismissed as a khawaga (an Egyptian Arabic word often used to denote someone is foreign).

“Oh, that makes sense! Khawaga!” someone would say, as if having fair skin and growing up overseas automatically means I have lost my culture or am too ‘Western’.

The result is, regardless of whether I lived in Egypt permanently or visited temporarily, I felt like a foreigner on the streets I called home.

I asked others who similarly have fair skin or look a ‘little different’ despite being Egyptian and found that they all had similar experiences.

But why?

White Advertising

Driving on the ring road in Cairo and sitting at restaurants and cafes, I noticed something in common: advertisements that were scattered on the highway or cast long and looming shadows on people enjoying their coffees often featured ‘light-skinned’ or ‘white’ men, women and children.

These men, women and children often had coloured eyes and looked ‘Western’ – despite a possibility that at least some of them were Egyptian or Arab.

Numerous academics and journalists have studied the increase in ‘white’ advertising. Some claim that the advertisements link skin colour to class, while others say advertisers are simply abusing societal assumptions that fair skin is more beautiful.

This, of course, isn’t unique to Egypt: in countries like India, Thailand and Pakistan marketers have been slammed for promoting fair-coloured skin as more attractive than darker skin. The “skin lightening” industry is strong in Asia and in more southern eastern African countries where whitening creams not only penetrated the markets but brought their harms with them.

Certain whitening creams were booming in the 1990s and early 2000s until an uproar broke out when studies linked the creams to skin cancer and other long-term damage.

In a bid to avoid the use of whitening creams, recent years have seen women across the region turn to bleaching. In Egypt, chlorine baths became temporarily popular in 2018 as a means to achieve fairer skin.

Egypt Historically a Fusion of Races

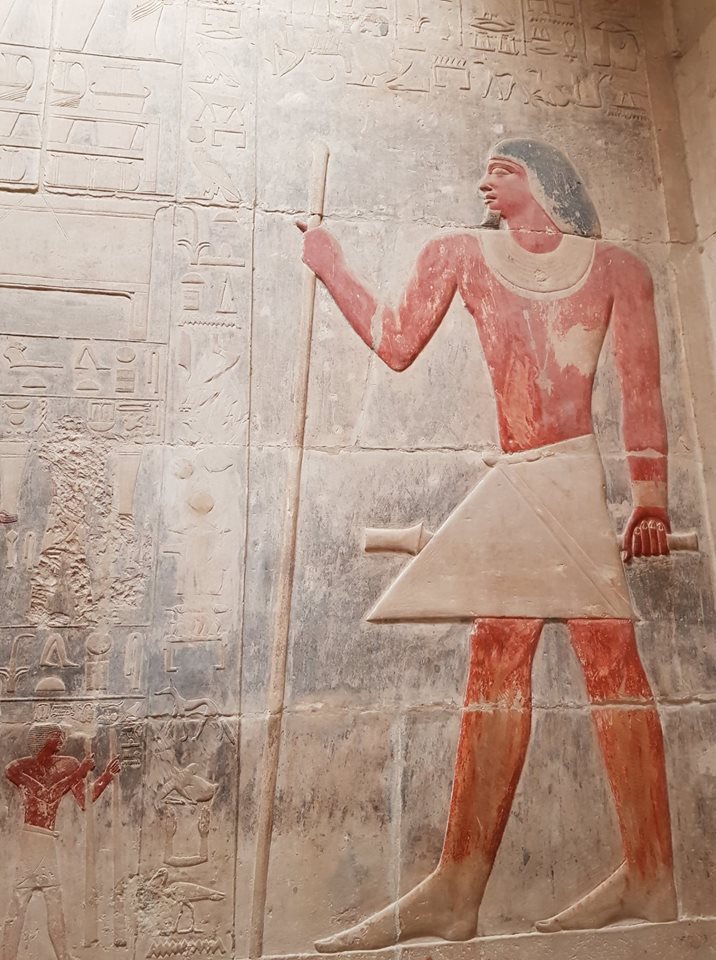

Egypt, however, has historically been a fusion of cultures and races – from Persians, Turks and Graeco-Romans to Africans (i.e. Nubians) and Arabs. Meanwhile, in ancient Egypt, skin colour varied by region and there is little indication that, at the time, skin colour was used to determine attractiveness or even used to distinguish between groups of people.

Egypt’s historical roots continue to display themselves today. It is not uncommon for Egyptians today to know of a great grandparent who was a Turk. It is also not uncommon for blonde and blue-eyed Egyptians to be found in certain villages around the country as a result of colonial forces intermingling with local inhabitants.

At the same time, the diversity of ancient Egypt – which consisted of all types of skin colours including darker skinned people – remains alive today in towns and cities across Egypt.

Today, though, there have been numerous accounts on social media and newspapers of discrimination towards dark-skinned Egyptians, and particularly Nubians and Sudanese.

While there are many studies as to the root of the idea that fair skin is more attractive or superior in modern Egypt, I wonder whether this can be tied to the media everyday people are exposed to: from films to billboards and television advertisements.

The over-saturation of fair skin in media, along with other historic roots such as attempts by the British during its colonial hey-day to promote ‘white’ as supreme, has likely contributed to today’s people starting to see skin colour as a first impression.

For Egyptians who don’t fit the “typical Egyptian mould” many appear to have developed in their minds, the impacts on their everyday lives are clear: if you’re too dark-skinned you are discriminated against, and if you’re too fair-skinned you’re approached with caution and assumed to be an outsider.

To be clear though, my experiences pale in comparison to those of darker-skinned Egyptians, such as Nubians. While I may be treated with bewilderment and curiosity, that privilege – and it is a privilege – does not extend to dark-skinned Egyptians who often face systematic discrimination.

The difference in treatment is a testament to some of the many issues that exist in Egyptian society.

I don’t propose any solution, but I do hope, given Egyptians’ pride in their ancient Egyptian and multicultural roots, that skin colour no longer remains a first impression, or even second or third.

Embracing diversity is key to building a stronger and brighter future for all Egyptians.

Comments (2)

[…] Egypt’s Problem With Colour […]

[…] Source link […]