Since its establishment in 1928, deception and fact falsification are, in my opinion, the basis on which the ideology of the group was formed.

The Muslim Brotherhood group, which was founded by the Egyptian school teacher Hassan al-Banna, has a long history of deception to the extent that Egyptians associate it with faking facts and misleading the mass today.

As a young journalist writing for English-language outlets, this fact was not clear to me for nearly two years.

The deception strategy of the MB succeeded in instilling an unlimited wave of sympathy towards the promoted stories of torture and forcible disappearances in me.

However, the recent propaganda that followed the execution of nine perpetrators accused of plotting the assassination of Egypt’s former general prosecutor raised many questions, even for me. The most pressing matter was, without a doubt, citizen understanding of the role of media and on how certain facts were losing their shape due to social media.

As a journalist, I admit that I ran many stories on a number of MB members who were labeled as ‘forcibly disappeared’; the stories that I wrote were defending them and calling the Egyptian authorities to unveil their fate, however, many of those members turned out to be IS militants or participants in militant attacks sponsored by the MB.

The MB’s ‘facts falsification strategy’ seems to have adopted a systematic plan, created by the International Organization of the Muslim Brotherhood, to conceal its members and claims of forcible disappearances. It also distorts facts through denying responsibility of its members’ involvement in terrorist crimes, as proven over and over through different judiciary entities.

Through the use of media outlets, namely social networking sites, this outlawed group is regularly accusing the Egyptian state of hiding, arresting and torturing its members.

The Brotherhood has not only misled citizens with deceptions, but it has resorted to asking for assistance from international entities while equipping itself with false reports on the human rights’ conditions in Egypt.

Subsequently are stories of numerous figures with terrorism affiliation; they carry evidence on how the MB affiliated media outlets, and the families of the concerned individuals falsely claimed that their sons were forcibly disappeared following arrests made by national security services. They feature the stories of three young Egyptian men.

Systematic allegations by the Muslim Brotherhood

There are three main stories that come to mind when thinking of forced disappearances in Egypt. While these are not representative of all the stories and all the cases that human rights organizations speak of, these are still an adequate example of how rumors of forced disappearances propagate.

MB-affiliated members and NGO’s, given the specific task of monitoring human rights conditions in Egypt, have published numerous reports on ‘random disappearances’ of people who were consequently proven to be militants of ‘Sinai Province’, members of the Brotherhood or any other extremist groups located outside Egypt.

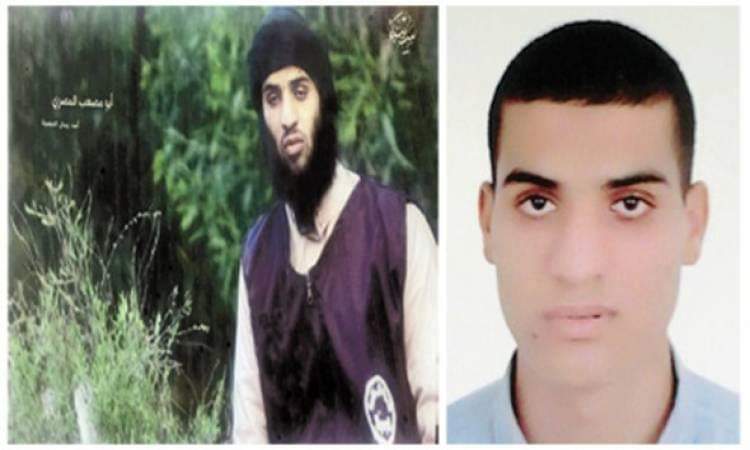

The first story is of Mohamed Magdy El-Dalyi, a student at the Faculty of Engineering at Cairo University; his name became popular when the Muslim Brotherhood claimed that he was subjected to forced disappearance in 2015.

At that time, his father announced that the Kafr El-Sheikh-originating student had disappeared while being out; he accused security forces of arresting his son, but these claims quickly ran short.

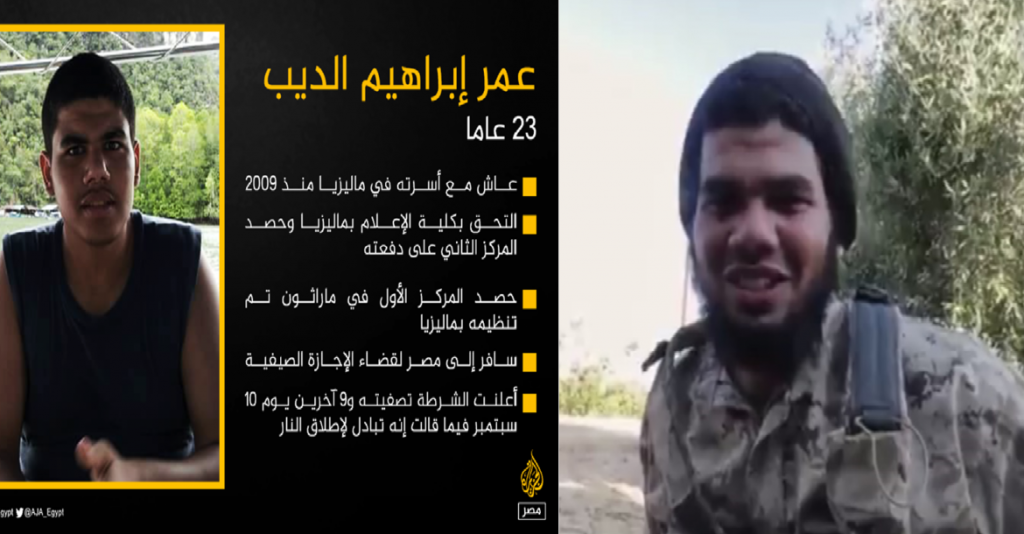

The second story is of Omar al-Deeb is the son of the Brotherhood leader Dr. Ibrahim al-Deeb. Upon his return from a trip to Syria, foreign Brotherhood channels broadcast that Omar was arrested in Egypt during his father’s visit; word quickly got out that Omar had disappeared by force.

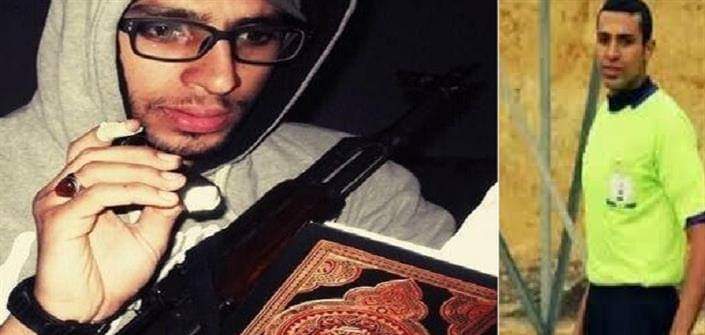

The third story is of Mahmoud al-Ghandour or ‘Abu Dajana al-Masri’ who was a young Egyptian who had supposedly forcibly disappeared in 2014 according to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The last story is of Abdel Rahman Osama; he was believed to have been subjected to a case of ‘forced disappearance’. His family along with political activists have maintained that he had forcibly disappeared at the hands of national authorities.

They launched a campaign on social media under the hashtag ‘Khatafo El Aris’ (They Kidnapped the Groom), which went viral on Facebook in 2015, following his ‘disappearance.’

Osama’s wife had said, in a televised statement dedicated to Al-Jazeera, that her husband was imprisoned for nearly two years before being subjected to the alleged ‘forced disappearance;’ however, he later appeared to be among the perpetrators of the Bahareya oasis attack on November 2017.

These stories bear remarkable similarities.

One element to bear in mind is that Egyptian society is quick to show sympathy, without knowing the entire truth, with cases of young disappeared men. Further sympathy is extracted as the media and the families of the so-called disappeared describe their offspring as perfectly respectable future ‘doctors or engineers’ in order to steer their reputations clear of terrorist activities.

Investigations revealing terrorism activities

However, despite the sympathy extracted and the brouhaha revolving these men, investigations revealed that their disappearances were not as simply orchestrated as portrayed.

The disappeared are often found in ‘Sinai Province’s’ own media outlets, through photos or video footage of them. If not, then their names appear in the statements issued by the Interior Ministry on recent arrests and security raids against terrorists.

In a video released by the IS affiliated group of ‘Sinai Province,’’ Mohammed al-Dulai appeared with his new IS name “Abu Musab al-Masri”; he had clearly adopted the extremist ideology of Jihadists and Tkfiris, calling to kill worshipers inside Sufi mosques.

As for al-Deeb, the senior al-Deeb introduced his son to the state of the caliphate; as a result, the young man traveled to war-torn Syria to join IS. Thus, he trained in using weapons and creating explosive devices in preparation for his return to Egypt where he planned to carry out hostile operations against army and police forces.

Omar El Deeb travelled to Syria to declare allegiance to IS and joins its ranks for what he called’ the victory of the right’, two years after the 2013 dispersal of Rabaa Al-Adwayia sit-in. After his trip, Omar returned to form a terrorist cell.

Despite claims of his forced disappearance, Omar appeared in a video, released by the IS affiliated group of ‘Sinai Province,’ where he is shown carrying a weapon and adorning the IS military uniform. He paid tribute to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of the IS, and acknowledged that he carried out many terrorist attacks against Egyptian army and police forces.

Both men’s forced disappearances claims, thus, masked skillfully their newly found terrorism activities.

Similarly, in 2013 Ghandour, a previous football referee, headed to Syria within relief convoys through Turkey. Upon his return, the 24 year old was arrested by the security services at home although he was later released.

After his release, the young man was unheard of for several months before eventually resurfacing in 2015. That year, he announced that he had joined the ranks of IS in Syria confirming that he was a sportsman-turned-militant.

Moreover, Ghandour appeared in a number of photos, holding weapons and raising the IS flag; the photos were posted through his personal accounts on social networking sites.

Later, Ghandour named himself Abu Dujana al-Masri; he announced through his accounts, that he would carry out a suicide operation in Iraq and that his account would close on Twitter. He was eventually killed in Ramadi four years ago.

Lastly, Abdel Rahman Osama’s story bore the same characteristics as the others.

On October 2017, anonymous militants launched an attack on police forces who were on their way to arrest them; the attack left 16 policemen dead.

Consequently, Egypt’s army launched aerial raids and ground operations against the perpetrators which resulted in their deaths. The army’s photo material depicted a militant’s corpse; he was believed to be have been MB member who had allegedly been a case of ‘forced disappearance’ by Egyptian authorities.

The photos, published by the army’s official spokesperson, raised questions about the credibility of some reports issued by non-governmental organizations on young Muslim Brotherhood members’ ‘forced disappearances’ cases in Egypt.

One of the photos showed the corpse of a young man by the name of Osama; the latter had been active on MB-affiliated social media platforms and he was believed to have been subjected to a case of ‘forced disappearance.’

These are but a mere examples of dozens or even hundreds of people who have joined terrorist elements. It is clear that, as an audience, we ought to be careful of allegations made by certain media platforms, especially when execution verdicts are being applied on militants or terrorists who have admitted to committing such crimes.

Any opinions or thoughts expressed in this article do not reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion piece, please email [email protected]

Comment (1)

[…] Source link […]