This year’s Christmas movie release in Egypt may pull you away from the lingering holiday spirit. It certainly did for me. Though the final moral delivered in the script seemed jarringly inconsistent with the story itself, Banat Thanawy (High School Girls) gave a raw, gritty, and at times empowering telling of the vulnerability of working class women on the cusp of adulthood.

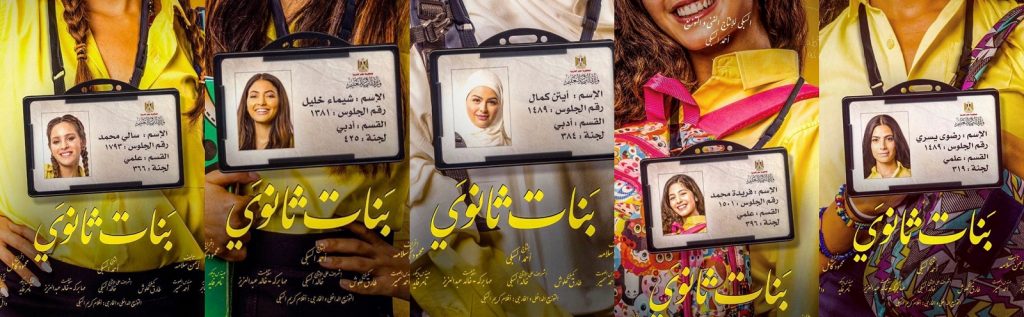

An Ahmed El Sobky production, the film is directed by Mahmoud Kamel and stars Jamila Awad, Huda El Mufti, Mayan Elsayed, May Elghety, and Hanady Mehanna — portraying a group of friends with varying personalities and unique struggles that reflect some of the hardships faced by Egyptian women in vulnerable circumstances.

The theme of struggling young women is a common one in Egyptian stories, however this film attempts to provide its own spin on it in a number of ways. Narrated through live Instagram broadcasts of Sally (Jamila Awad), Banat Thanawy tries to bring these girls’ stories decidedly into the digital age in its most current form. The story also seems to have done its best to delve into the main characters’ relationships with each other as much as into their relationships with the men in their lives, giving them agency and control in many of the actions they take.

While Sally is holding her own in a dubious love story with the rich young Alaa (Mohamed Al Sharnouby), Farida (Mayan Alsayed) is making sense of her lonely life as a poverty-stricken orphan. Ayten (Hanady Mehanna) is a girl with a talent for singing who is falling prey to the temptation of religious fanaticism being peddled to her by Ashraf (Mohamed Mahran) an uneducated young man who wants to marry her. Vain and jealous Radwa (Huda El Mufti) is boldly trying to seduce her married Psychology teacher Nagy (Tamer Hashem), and Shaimaa (May Elghety) is attempting to break free from the one-room home she shares with her abusive and drug-abusing father.

This film, like many others, falls into the trap of casting five women who fit into mainstream beauty ideals. However, the young actresses’ performances are undoubtedly worthy of commendation. In spite of the fact that they do not stem from the same environment as the characters they portray, their effort to bring authenticity is noteworthy.

This was particularly noticeable in a memorable scene where Farida, Radwa, and Shaimaa skip school and visit a shopping mall together. The childlike joy the actresses showed at the sight of designer handbags and watches and their shock at the astronomical prices was genuine and endearing.

By weaving them into the girls’ stories, Banat Thanawy lays bare a number of glaring problems in Egyptian society such as class separation and elitism, religious fanaticism, substance abuse, and violence against women, and tries to faithfully recreate the real coping mechanisms and responses young women may have to these issues.

Many topics that are mostly considered taboos — such as the etiquette of wearing the veil in places where it is a de facto dress code, menstruation, rape, and suicide — are addressed in the film, however the choice of struggles was not outstandingly original.

The film fell into the occasional stereotype (most notably the talented, religious girl who finds herself at a crossroads of choosing between her artistic passion and her faith), and failed to have a religiously inclusive set of main characters, as is the case in most films that don’t tackle religious differences as a main theme.

The quality of the screenwriting and directing shows most clearly in the story’s climax where the girls’ struggles reach dramatic and almost tragic apexes. As a viewer, I felt as though the tension had been building quietly, barely noticed, throughout the film, and was released with a forceful gasp and quite a few tears as the characters face the consequences of what they had done and what had been done to them.

But while four of the five girls in the story get a reasonably happy ending, it is important to remember that this is often not the case in reality. And here is the aspect where, in my view, the movie fails. The lesson Sally presents as the moral of their story is that it’s not all wrong to be overly protective of your daughters given the dangers young women face. However, the entire story told before that lesson is uttered runs counter to increased protectiveness as a response to these dangers.

In the culmination of almost every big conflict, the girls’ tendency to turn to and trust each other is what helps them prevail. The presence of mind they show proves that in spite of — or perhaps even because of — the vulnerable circumstances they are in, they develop a strength that is worth highlighting without going on to turn them into victims in need of protection. It also seems counter-intuitive to me that this film — with its empowering themes and its critical view of recurring forms of violence against women — should seek to promote further protection rather than to fight the diseased habits in society that make women vulnerable in spite of their strength.

Comment (1)

[…] womanhood in Egypt has been represented in some films and series like Banat Thanawy (2020) and A Girl Named Zat (2013). While these works may not delve into the same philosophical depths as […]