When a tragic blast hit the city of Beirut in early August, killing nearly 200 and injuring over 6000, a heavy weight of sadness fell upon the Region.

This explosion did not mark the beginning of strife in Lebanon. It occurred after months upon months of protests and mounting pressure, and against the backdrop of an ever sharpening economic crisis and lasting struggle for social and political reform. The damage the explosion inflicted on the city became a final straw to many.

With faith in all members of the government and political elite thinning and the fallout of the various crises accumulating, people in Lebanon began to fear that there was no way out of the turmoil.

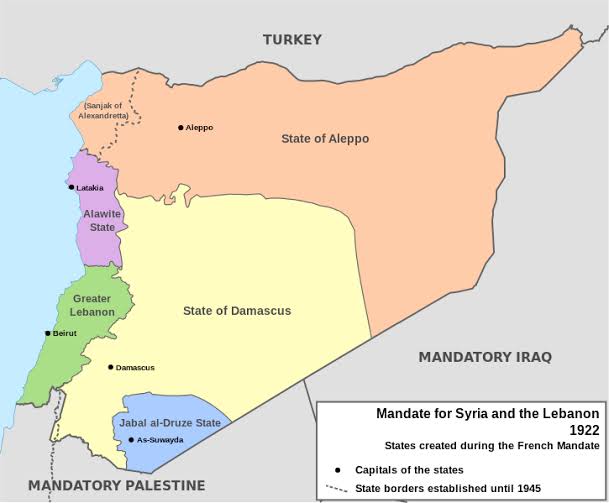

Of the sympathy that poured in from around the world, the solidarity of one particular head of state stood out: President Emmanuel Macron of France, Lebanon’s occupying power between 1920 and 1943, visited Beirut to pay his respects and express his support.

During his visit to Lebanon, Macron did not only meet with his Lebanese counterpart Michel Aoun and other incumbent politicians, but also with Lebanese citizens on the streets of Beirut. As Macron was welcomed by the desperate and struggling, a contrast was struck by the implicit knowledge that no Lebanese politician could do the same without risking the wrath of the fed up citizens.

This was the first of two visits aimed as a French outreach to the people of Lebanon, the more recent of which took place in early September. It saw Macron embracing Lebanese star Magda El-Roumy and having an audience with the icon Fayrouz, in which he bestowed upon her one of France’s highest honours.

The French President’s appearances were particularly well-received by public opinion, and among the responses was a Instagram story made by Lebanese-American actress Mia KhalifaInstagram story made by Lebanese-American actress Mia Khalifa, who called on the French rule to “come back”.

This arguably humorous exclamation, however, was echoed in all earnestness by a surprising number of Lebanese people when a petition calling for France to govern Lebanon for a period of 10 years received an astounding 60,000 signatures.

60,000 is by all means a minority, and a large number of Lebanese citizens criticised and opposed the idea, but it demands contemplation for such a movement to gain momentum at this critical time. The call for foreign, colonial intervention lies in profound contradiction with protests calling for increased popular involvement.

The Lebanese population is a patchwork of political and religious identities, each of which has its place in the country’s elite. In recent protests the widely repeated slogan was “killon ya’nai killon” — all of them means all of them — demanding a complete removal of the entire political class.

While political turmoil is plaguing most of the world, Lebanon’s struggles are unique. Discontent with the incumbent in some parts of the world can simply mean support for the opposition. But the Lebanese political class is a mosaic representing the many and various sectarian and political and groups, and is rejected in its entirety. In fact, the very idea of a political system based on sectarian divisions is what is driving the discontent of so many in Lebanon.

The constructed romantic image of the bygone era of colonial rule that exists in many formerly colonised countries, including Egypt, especially amongst some of its older and wealthier citizens, is one that hinges on discontent with the status quo coupled with a forgetting of the reason scores of states fought for their independence throughout the 20th century.

Colonial powers, as history has proven time and time again, sought control of foreign lands around the globe to exploit their resources or geostrategic value for their own interests, rather than the interest of the land and peoples they sought to subjugate. And like any country now independent from colonial rule, Lebanon’s fight for independence was motivated by the French mandate’s disregard for Lebanese interests.

The incontestability of people’s right to self-determination has made the idea of foreign rule obsolete and archaic; out of place in current global politics.

It may be argued that this colonial nostalgia is an indictment of the post-colonial independence state as a whole. However, colonial nostalgia is precisely the wrong answer to the frustration and dissatisfaction with this legacy.

The biggest shortcoming of the post-colonial state, in Lebanon as in many other post-colonial countries, is its failure to engage and institutionalise wide public participation in governance.

This can never be remedied by recalling foreign rule, a relic of a world past, but by widening the application of self-determination, so that it does not simply address the national identity of the ruling class, and moves further towards good governance anchored in wider and more institutionalised participation by empowered citizens.

Nostalgia is and easy reaction, but it does not provide a solution to current problems.

*The opinions and ideas expressed in this article do not reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team any other institution with which they are affiliated. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comment (1)

[…] Colonial Nostalgia: Macron Brings Stockholm Syndrome From Paris to Beirut […]