Even though Charles Duhigg’s book The Power of Habit has been around for nearly 10 years, the changing environment of work, physical health, and well-being has made it more relevant than ever. The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to many people’s routines and schedules being upended, and much of the structure afforded us by our places of work or study is no longer available to us.

In his book, the Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter identifies and describes the development and importance of habits in individuals as well as in organisations and societies, laying bare just how much of what we experience and decide is a result of our habits.

I reached for this book because I knew that if I wanted to live a healthy and balanced life, I had to be intentional about it. Like many others in my age group and circumstances, I am trying to build the toolkit that will allow me to navigate the ever more fraught reality our generation is in long gruelling workdays that can result in physical inactivity, poor nutrition, and little time to care for one’s mental well-being.

These challenges were taken to a whole new level when I found myself working from home most days, with no 9 to 5 to guide my sleep schedule, no office hours to force me out of the house, and little to know interaction with friends and co-workers.

I was not waking up or going to bed when I wanted to, I was quick to reach for unhealthy food, hours of work began bleeding into the hours I was meant to have for myself, and I found myself skipping the hours of exercise that had always been sacred to me. Reading Duhigg showed me that so many of these actions were decisions I made unconsciously due to habit.

While writing this, I reached out to other young Egyptians to see if anyone else was experiencing similar struggles of trying to retire habits that were standing in the way of the life they wanted to lead. Unsurprisingly, most of the responses I got were very familiar.

“I stopped the habit of checking my phone as soon as I woke up for like a week but went back to it anyway,” Maureen Guirguis told me. Surfing social media upon waking up is one of the most common struggles of our generation, and one I am personally dealing with, too. Though it may have been a conscious decision the very first time we did it, it has long since become a habit for most of us.

Another story came from Fatma Eita, who in spite of sticking to nutritious foods throughout the day, found herself reaching for unhealthy snacks before bed. This one hit close to home, as I have been going through the very same struggle for the past couple of years, resulting in a gain in weight I haven’t been able to undo since. Again, this is a habit, not a conscious decision.

These are two of a number of other examples of decisions that our brains automatically take out of habit rather than conscious thinking. We seek to overcome these struggles to live healthier, more fulfilling lives, but we don’t know how we developed these habits to begin with, or why they are triggered, which makes getting rid of them all the harder. So how can we solve this problem?

Duhigg’s golden rule simply stipulates: “You can’t extinguish a bad habit…

…you can only change it.”

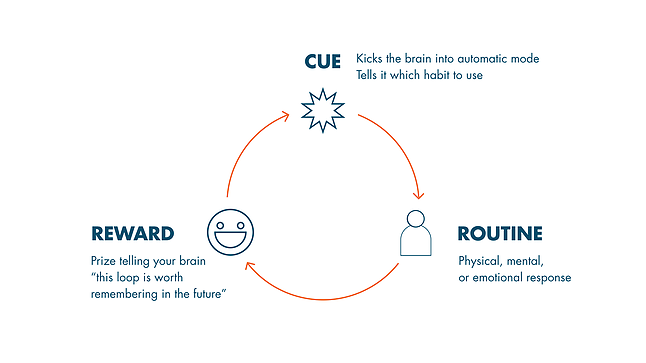

The author identifies what he calls a ‘habit loop’ as three stages; a cue, a routine, and a reward. When the brain receives the cue, it becomes conditioned to go into a sort of autopilot mode, leading to the routine. This routine is the undesirable action we take. Finally, the reward is the motive that drives this entire loop.

The author’s main argument is that you can’t get rid of the routine, but you can always change it by taking out the undesirable part and replacing it with something better for you. The book proposes a framework to identify the cue and the reward, and change the routine to what we want. Let’s see how they work:

1. Identify the routine

This is the easiest part of the process. Whether we want to stop snacking on cookies, doom scrolling, or sleeping at dawn, the target here is to pinpoint the habit we want to change. Duhigg used an example from his own life: while at work, he would leave his desk, go to the cafeteria, buy a cookie and chat with colleagues, and then return to his desk.

2. Experiment with rewards

This is the stage where you try to figure out why you turn to the habit you want to shed and what reward it is you are craving. To build on the author’s example, Duhigg tried different scenarios: Buying a different item at the cafeteria, chatting with colleagues elsewhere, going on a walk instead, or bringing an apple from home to snack on. The point of these experiments was identify exactly what it was you are craving. Only once you have done that can you come up with alternatives to successfully turn the habit on its head.

3. Isolate the cue

This part requires the most time and effort. According to the author, the most common cues that trigger habits are location, time, emotional state, other people, and immediately preceding action. He recommends keeping a record of those five things for a number of consecutive days, keeping an eye out for a pattern. In Duhigg’s case, he was at his desk at a quarter past three in the afternoon, feeling tired, surrounded by no one, right after finishing a task at work. He identified his trigger as the time of day. Other common triggers are boredom or stress leading you to doom scrolling, or associating your moment of arrival at the office with the day’s first cigarette, or a certain person you usually get junk food with.

4. Have a plan

Now that you have identified the trigger, the habit, and why you are sticking to it, you’re almost there. Duhigg suggests coming up with a plan of action, along with a few backups. Duhigg’s plan of going to a friend’s desk for a chat instead didn’t always work, because that person wasn’t always around. And when it fell through, he went back to the habit he wanted to change. That’s where the backups came in handy. But it is key to know that the growth of your success rate will most likely not be linear. It will require focus, observation, and patience for trial and error. The author’s success rate increased from one day to the next, and he eventually stopped going to the cafeteria to buy that cookie.

What came through to me from Duhigg’s book was that simply deciding that I had to break a habit would not get me anywhere. But by reaching its root, understanding its cues, and conditioning my brain to seek its healthier replacement, I would be far more likely to succeed in distancing myself from undesirable habits standing in the way of the growth I’m seeking.

There is certainly no one-size-fits-all solution to the challenges of habit changing, and you may have developed your own tactics to stay on track. From my experience, this framework may require some effort and discipline on your part, but the truth is, so do most things that last. Taking this approach can help you gain a deeper understanding of where your bad habits come from and what motivates their development. Getting a grasp of the trigger and the motive is a key step to changing that bad habit. Aristotle once said: “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”

This piece was co-authored with Egyptian Streets writer Amina Zaineldine.

Comments (0)