Gucci, Fendi, Prada, and Yves Saint Laurent knockoff clutches and shoes fill small Heliopolis shops. They sell, despite their clearly poor manufacturing quality, for up to EGP 3,000 (USD 156).

The international fashion industry is a mammoth, constantly evolving with new styles and globalized trends. Fashion e-commerce in the Middle East alone accumulated USD 1.6 billion in 2018, with Egypt projected to reach USD 300 million this year.

In seeking recognition and success, however, fashion labels are often subjected to copyright infringement and theft—violations that seem irrelevant to many not working in the industry. Although counterfeit goods are often associated with the Chinese market, the practice of buying little, faux trophies of status has reached all corners of the world—Egypt included.

Azza Fahmy, a staple Egyptian jewelry design house known for its resplendent use of precious stones, toils one design at a time, with entire collections taking over a year from conception to manufacture.

One of its prized designs—taken from the Pharaonic Collection—is a Vulture Collar depicting Nekhbet, the ancient Egyptian goddess of royal protection. Inspired by the amulet of the formidable Egyptian queen Ahhotep, the necklace is characterized by its symmetrical open ‘wings’, sitting at 18 carat gold and silver. Paying homage to its inspiration, its sheer weight, and caliber of craftsmanship, is fit for royalty.

Currently, the piece sells for USD 4,660 (EGP 89,445).

Yet, far from prying eyes emerged a copy of the same necklace, for nowhere near the hefty price tag, fabricated by another local jeweler. Unsurprisingly, this invoked the wrath of the brand which initially birthed the design: Azza Fahmy filed a lawsuit— and won.

Years of work: stolen in a moment?

Since 1969, Azza Fahmy has been a dominant force in the field. Stemming from the fine traditions of jewelry-making in Egypt, Azza Fahmy’s jewelry is characterized by its intricate craftsmanship, which takes into account modern technologies and theories of application.

For Azza Fahmy, each piece of jewelry is centered around an inspirational motif, with Arabic calligraphy and gold-silver combinations being some of the brand’s signatures. Thus, the design process for each collection is rigorous, taking between 16 to 18 months from concept to launch.

“It’s not only about the time frame it takes us to put a collection out, but it’s the fact that it has taken us more than 50 years of know-how to get here. People who steal our collections are essentially just taking the product, recreating it, and in most cases selling it for a cheaper price,” explains Fatma Ghaly, the Chief Executive Officer of Azza Fahmy.

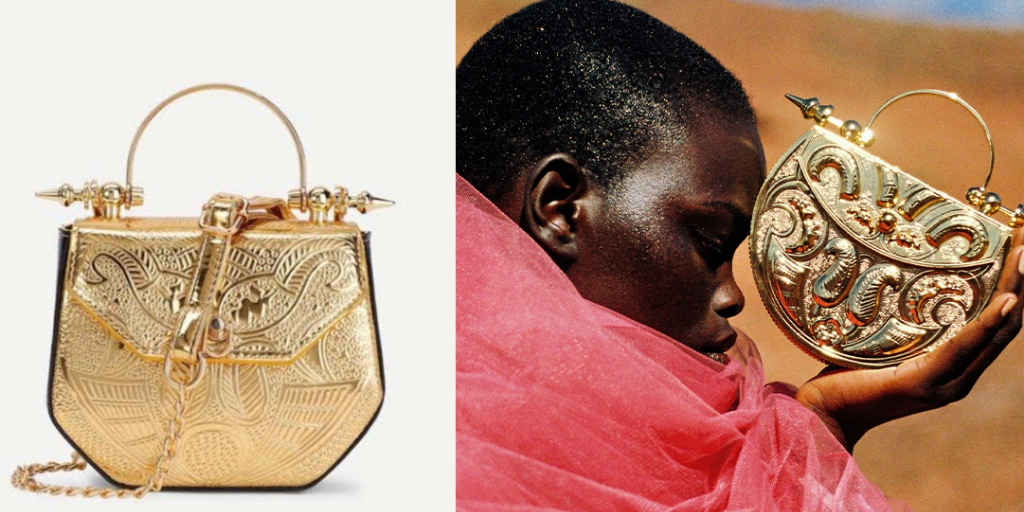

Similarly, Egyptian bag design barons of Okhtein, Aya and Mounaz Abdelraouf, have been dominating the fashion scene since they established their luxury brand in 2014.

The two sisters’ brand has been at the forefront of the Egyptian market with high quality leather products, aiming to redefine the luxury fashion industry.

Quintessentially Egyptian, Okhtein’s pieces have been inspired by Cairo’s architecture and local craftsmanship, especially Khan el-Khalili artisans, who the sisters have taken inspiration from.

For Okhtein, the quality of their pieces is what makes them an exceptional brand. They managed to succeed not only in Egypt, but have become trailblazers, producing their products in Spain and the UAE as well.

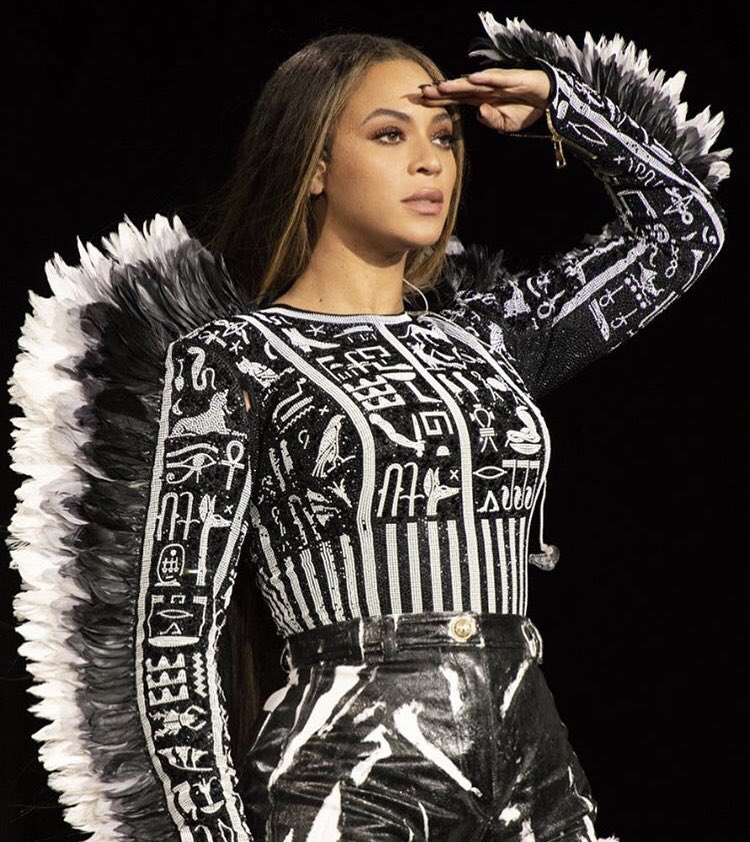

Okhtein’s products are available at renowned retailers around the world, including Harrods, Bloomingdale’s UAE, Harvey Nichols Riyadh, and Saks Bahrain. Celebrities, including Kourtney Kardashian, Beyoncé, and Gigi Hadid are among the many superstars who have flaunted their Okhtein handbags.

Much like Azza Fahmy, however, Okhtein has grappled with the emergence of imitations within both Egyptian and international markets.

“We have been fighting this fight since 2015, back when Okhtein had been out on the market for only a year,” explain the two Okhtein founders to Egyptian Streets.

Early on in their creative journey, Aya and Mounaz fell victim to the first of many unsettling infringements. One of their bag manufacturers at the time, a brass workshop, stole the design of their molds, which sat “at the heart” of their signature brass clutches.

To add insult to injury, the factory threatened to copyright the molds.

“We produce our pieces using the highest quality of leather and brass, but the problem is that people are not only comfortable with copying our designs, but they also see no problem with the idea itself,” says Aya Abdelraouf.

Ghaly echoes Okhtein’s Aya’s sentiment. Reflecting Azza Fahmy’s insistence on the protection of intellectual rights, she expresses that not enough awareness is raised on the topic in Egypt.

“One of the biggest issues is that [imitating a design] is often not considered theft, people don’t think they are doing something wrong,” explains Ghaly, adding that no artist or writer would ever stand for their work to be reproduced under the name of someone else.

Intellectual property lawyer Dina Amer, from Tamimi & Company, agrees: “We don’t have the culture of intellectual copyrights. It’s always a concern for business owners and people who appreciate the art, but for the general public, the culture of copyrights is not known.”

Both powerhouses, Okhtein and Azza Fahmy, are represented by Tamim & Company. Yet, as powerful as that representation may be, an appetite for fake goods remains at the crux of the counterfeits crisis.

The pivotal factor: consumers who love fakes

In one of the Heliopolis shops, Egyptian Streets asked a counterfeit products seller if he sells imitation Okhtein bags.

“If you want, I can get you one, but you need to be ready to pay up to EGP 9,000 (USD 468),” nonchalantly replies the storeperson, who willingly adds that he finds the brand overpriced.

The issue with design theft is with those consuming the counterfeits as much as those creating them.

In a country like Egypt, where 29.7 percent of Egyptians live under the poverty line, precious brands and items of wealth are coveted as status symbols: expensive cars, designer bags and shoes, and, most recently, jewelry.

“I don’t usually buy fake items, unless they have really good material. I mainly find the sellers on Instagram accounts and in thrift stores as well,” notes Hala Walid, a 19-year-old university student.

“Sometimes I know I can’t get my hands on the original item anytime soon, so I opt for a fake one, as long as the fake item is worth the money.”

Exasperation and frustration equally dripping from her voice, Azza Fahmy’s CEO explains that the idea of stealing a design, in Egypt, is not considered a harmful practice by people.

The Okhtein sisters are inclined to agree.

“There were times people posed with fake Okhtein bags, and tagged us on social media,” says Mounaz.

“People showed up at events with the fake bags, and when we confronted them, they would say ‘I’m sorry but your price points is too expensive’, or they just play dumb and say they didn’t know it was fake.”

Across Egypt, restaurants and businesses do not engage in the entire creative production from scratch, but resort to printing photos and designs from the internet. Only in more recent years have debates surrounding attribution to rightful creators been raised.

This summer, controversy surrounding Cairo’s underground metro murals erupted. Russian artist Georgy Korasov accused Ghada Waly’s studio of plagiarizing his ancient Egyptian inspired designs after strikingly similar use by the studio of designs in a Cairo metro station.

“My paintings were used in the Cairo subway without my permission and even mentioning my name!” wrote Korasov on his official Facebook page. The accusation prompted a swift response from the National Tunnels Authority and RATP Dev Mobility Cairo, who both apologized to the artist and to the public for the incident. In their joint statement, the National Tunnels Authority and RATP Dev Mobility Cairo, who had commissioned Ghada Waly’s studio to create the designs, stressed that intellectual property was an important right to protect.

Divergence: between inspiration and imitation

When it comes to the fashion industry, inspiration and imitation overlap. Many Egyptian local brands draw inspiration from Egyptian history, mainly from the Coptic, ancient Egyptian, and Islamic cultures and aesthetic influences.

Take the 2021 Spring Summer Collection by Dior, was inspired by “multiple languages” in fashion, heavily dabbling in Balinese art crafts, dousing itself with the influence of “Endek Ikat” a technique which translates into an array of unique Balinese motifs. Similarly, a 2020 Victoria & Albert museum exhibit on the history and legacy of the kimono revealed the full extent of its serving as inspiration in modern day habit wear. Then, there is also the matter of the blue and white keffiyeh, a well-known symbol of Palestinian nationlism, culturally approproiated by Louis Vuitton for USD 705.

Ancient Egyptian motifs in particular have been the subject of replication that knows no bounds: Zuhair Murad’s 2020 Spring collection, Chanel’s 2018/19 Métiers d’art collection, Elie Saab 2017’s collection, Katy Perry’s ‘Dark Horse’ (2013), Beyonce’s Balmain outfits during 2018 Global Citizen Festival among many others have replicated these motifs.

How, then, does one differentiate between the borrowed and complementary, versus the outright stolen? And does it still constitute theft if the ideators of these designs were never brought to light in the first place?

“You see it in ancient Egyptian designs, how many designers have been inspired by ancient Egypt all over the world? But none of them have done the exact same thing as the others. All the big houses have been inspired. Same for Mexican culture, for example, but that doesn’t mean you [the brand] don’t have the right to protect your own designs,” rationalizes Ghaly.

“We never imitate anything. We are always inspired by cultures. When you’re inspired by something and you create your own designs, you have every right to protect it.”

A lesson for emerging designers: prioritize, register, and fight

But not all hope is lost: Egypt’s legal system carves out a way for brands to protect their work. In working with the government, it is possible for brands to go through the motions of protecting their intellectual property.

In simple steps, once a brand files a design registration at the Fine Art Sector in the Ministry of Culture in Egypt, the design is protected from the date of its filing. Unless it is contested because another individual had registered a similar design, the brand is granted full protection.

“Registering the logo for any brand is crucial, no matter the market it will operate in, ” says Ghaly. “But then, another layer is registering the designs, trademarking, and copyrighting the designs themselves.”

For Okhtein’s Aya, it is important for all upcoming brands to think ahead and prepare their products for possible challenges.

“We advise and support brands to take the time and precautions to register their designs, but they have to be smart about it. For emerging designers, it depends on the vision they have for their brand. If they plan on expanding their brands globally in the future, it goes without saying that registering and protecting is a must. But if they’re taking their brand as a side hobby that will eventually end at one point, then it’s just an added cost and effort for them,” explains Aya Abdelraouf.

And if all else fails, then the designers can file a lawsuit against those fabricating the fakes.

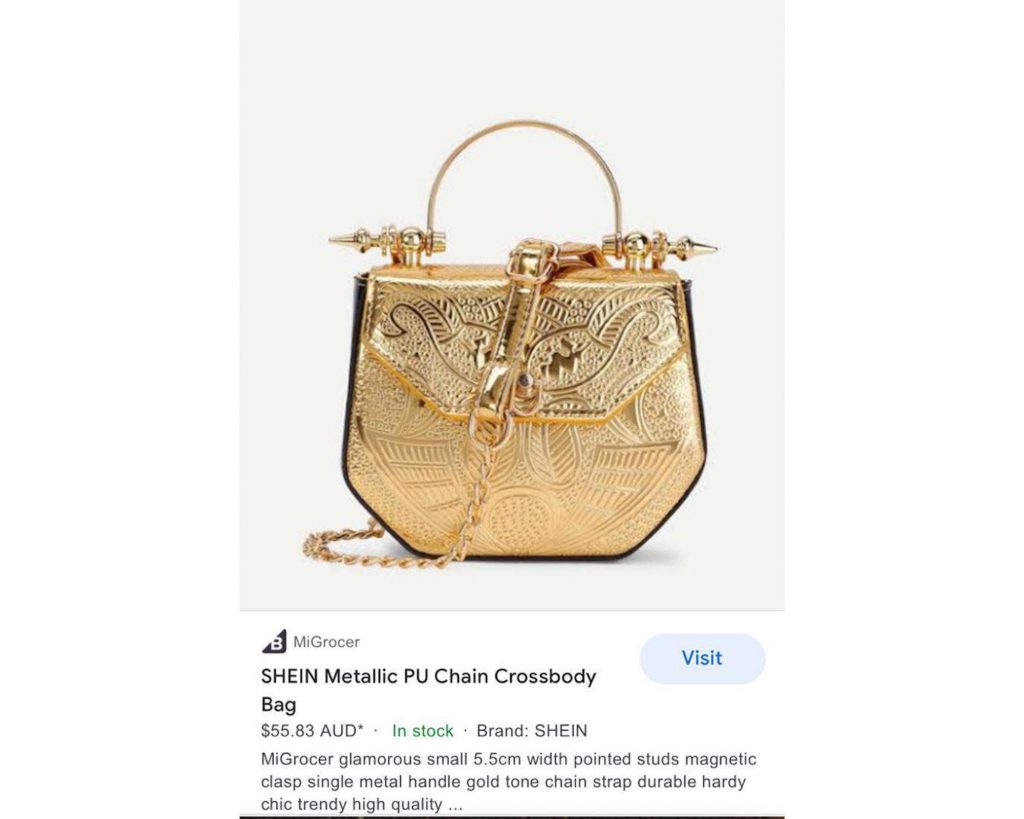

Recently, Okhtein won a lawsuit against online Chinese fast-fashion giant SHEIN, which was replicating their famous brass bags and selling them on its website for just USD 14.

“SHEIN replicated our brass bag, but used plastic material. The startling issue is that Egyptians started buying the copied bags from SHEIN. Not only were we spotting people wearing the fake bags, but there were also famous Egyptian fashion bloggers who would tag our Instagram account,” explains Mounaz.

The process of filing a lawsuit against imitators varies, but it mainly depends on the amount of evidence gathered against the infringers. According to Tamimi & Company, this process can often take up to 15 months.

One of the most effective measures employed by law firms to stop ongoing infringements is to conduct administrative actions, or, in other words, raids.

“Raids are often pre-planned. When we launch raids, we seize the samples and products, they are then checked for counterfeit. If the report concludes that the designs have been stolen from others, the court decides the discretionary punishment against the imitators,” explains lawyer Abdel Rahman from Tamimi & Company.

By relentlessly pursuing the manufacturers of fake, brands show that their desire to protect the original designs is also a form of raising awareness about repercussions.

“The objective of pursuing these cases is not only purely for the legal side of things, but to make sure that people know that this is not okay,” explains Ghaly.

Nonetheless, as much as the fight for intellectual property is a priority for many business owners, there is also the matter of affordability.

“The cost of a lawsuit is based on what the owner or company seeks. Some owners seek compensation from the violations, and they weigh the options and benefits. We can send a notice to the imitators as well, because it’s way less expensive to just notify or warn against pursuing legal actions. Some brand owners want the enforcement of their rights, and want to make sure their imitators will pursue this legally,” explains Abdel Rahman.

For Okhtein, lawsuits are not only costly, but they also take a lot of effort.

“It costs no less than USD 1,000 (EGP 19,000) locally and starts from USD 2,000 (EGP 38,380) upwards internationally. Then, there are lawyer fees to factor in as well,” explains Mounaz.

“So when designers create a knock off, it is very damaging and demeaning because we invest a lot of money in our designs. Everytime we launch a collection, we are always afraid that it will be stolen, because it will always be an added cost, and you end up registering every piece.”

Despite winning their respective lawsuits, the struggle pressists for both Azza Fahmy and Okhtein.

“If a lot of businesses are doing the same thing [fighting fakes], then that becomes a dialogue, and then it gets supported by the authorities, and then consumers can start not accepting it as well. It’s a full cycle,” explains Ghaly.

Both brands believe that raising awareness and engaging in dialogue are vital avenues for combating counterfeits. Not only does design thest harm individual creators, but it deconstructs the creative battery as a whole, whereby creatives lose drive and motivation.

In a climate that does not seem to appreciate originality and hard work, designers are left with burnout in a never ending fight against their imitators.

Comments (0)