My friends and family back home had been recovering from a recent war, but they were never short on hospitality. Each day during my trip back to the homes of relatives and friends, we were greeted with feasts, rooftop chats and sweet tea to reminisce about our sweet childhood memories. We went to the beach almost every day. It’s true, those Mediterranean waves can wash away all lingering pain.

I never imagined that this would be the last time I would see many of my family members, friends and their loved ones. The last time I would see my home. The last time I would see Gaza as it once was.

On the morning of the 15th of October, I woke up to a phone call from my father. My father usually texts, so I instantly felt a pit in my stomach grow.

With a shaken voice, he was struggling to get out the words to tell me what had happened.

“Your uncle Mahmoud was killed, your aunt Maryam…. Our family ya baba…25 people..”

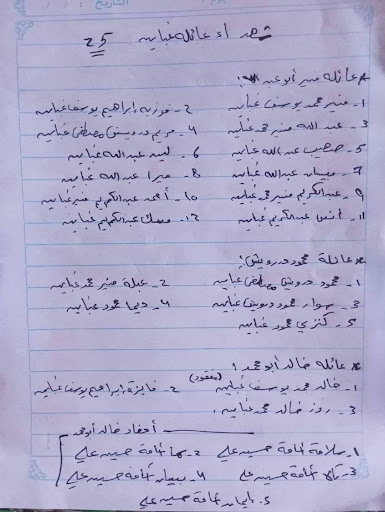

He hung up without finishing, the words were too heavy to utter. In shock, I open up Facebook and see proof of the massacre and the list of names. “Martyrs of the Ghabayen Family 25”.

One single Israeli airstrike, consisting of a missile made on US land, killed my uncle Mahmoud Darwesh Ghabayen, my aunt Maryam Darwesh Ghabayen, my great aunt Faiza Ibrahim Ghabayen and their entire families, including their spouses, children and grandchildren.

All of them had relocated to the south of Gaza along with thousands of other Palestinians after being told by occupying forces that it is a “safe zone”. The day before they were killed, my uncle Mahmoud called my mother and told her that they had found a half constructed building, missing windows and many walls, to stay for the night. Other relatives called him to seek refuge and, despite how small the space was, the bombardment was so intense in the north that he could not turn anyone away.

No one could sleep. The building was too crowded and too cold. The children were crying and screaming as bombs dropped around them. Uncle Mahmoud was planning to go find anything he could to keep the children and the rest of the family warm. He heard that a school nearby might have some food to spare and plastic wraps for warmth. He told my mom jokingly “Don’t worry, we are safe, we got each other and room for more.”

My uncle Mustafa, who was sheltering in another building, received a text about the bombing.

He hurried to the scene with civil defense and community workers to find that it had turned into dust and rubble. Screams were still echoing from within the rubble when they arrived. He dug with his hands. They all dug. Soon the screams turned into silence. They managed to recover many but not all.

The faces we grew up with were wiped of all features. Uncle Mustafa could not even recognize his own brother. The children could only be identified by their clothing, which was covered with a layer of gray dust. As the saying goes, All dusted in gray, “no difference between a stone and skin tone.”

Twenty three of our family members were laid out on a nearby street in multiple rows of body bags; two others, my little cousin Kenzi and my great uncle Khaled, were still missing under the rubble at the time. There was no room in the freezers or even in the ice cream trucks that had been converted into mobile morgues.

Uncle Mustafa was alone.

While other family members of his were still alive, the roads were too dangerous for anyone to travel on. The following morning, he buried them in a mass grave. He had no time to mourn. In Gaza, there is no time for the living nor the dead.

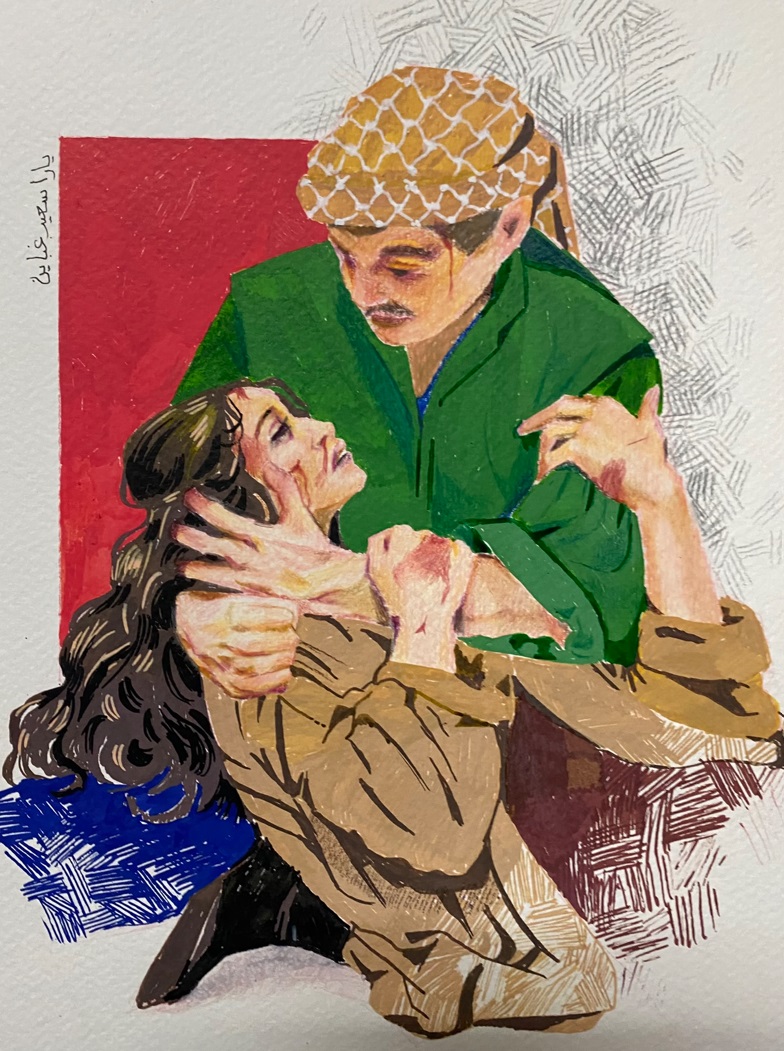

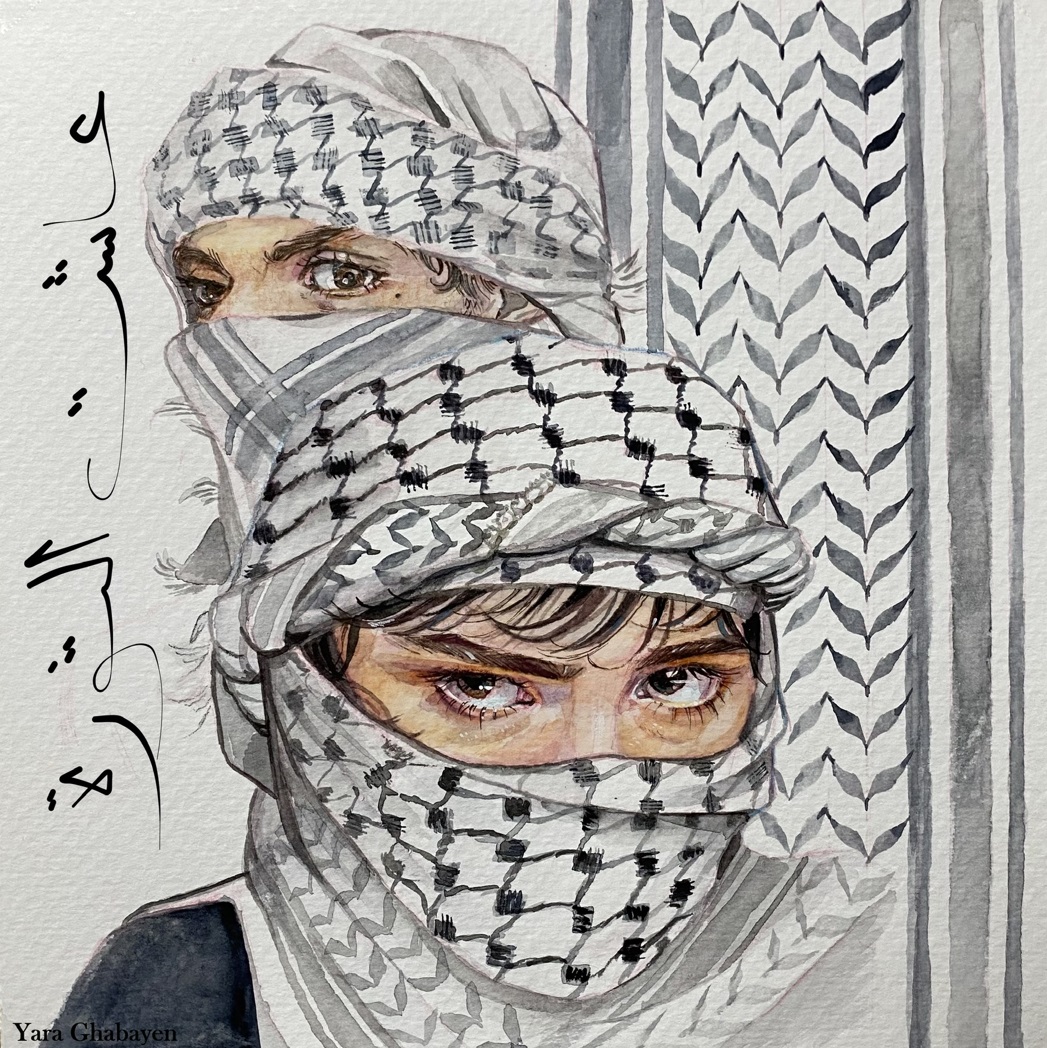

During my last visit to Gaza, Uncle Mahmoud and his family asked me if I still painted and drew as I had done when I was a child living there amongst them. I was too ashamed to respond that the trauma of war was still great. Despite having left, my whole world was still there.

Every bombardment I read about while abroad reopened a wound I could not heal. As a child, I had hoped art would give me a voice, but most of the time, as the violence continued, I would just end up feeling unheard and betrayed. So, I had largely stopped painting and drawing, with the pain lingering inside me. But, a part of me thought, how could I feel this way when they are the ones who are still under direct threat?

Later, reflecting on that visit, and being asked if I still paint, I realized that I was being heard. Uncle Mahmoud, my cousins, my friends in Gaza – they were always listening. I was just too focused on the wrong audience.

As a child in Gaza, I was praised by Europeans on humanitarian trips to my hometown, telling me how my art showed them I was brave and how this will free Palestine. To outsiders, art, amidst war, was romantic.

In the art world, much of the same narrative exists: your art has to be rooted in pain for it to be valid and reach an audience and that trauma creates great, popular art. I reject that notion. I did not want to be glorified, be called brave or be turned into a symbol, when all I was doing was crying out for help – when all I wanted was help. I was told to be a voice to the world rather than to my people in Gaza. The world was not listening, but my family, friends, and loved ones in Gaza were.

My story is not unique. I do not know a single Gazan who has not lost a family member, a friend, a neighbor. Heba Zagout and Mimana Jarada are among the many artists killed since 7 October.

And so, I will paint. I will draw. I will never stop creating art. Because, they are listening. Our art is for our uncles and aunts, our martyred families and friends, and all those in Gaza who find some form of connection to it. Our art is our voice.

Click here to see more of Yara’s art.

Comment (1)

[…] post Art in Gaza: Our Palette, Our Homeland, Our Voice first appeared on Egyptian […]