Ninety percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan are living in poverty, according to a new report, but their employment rights are limited because their host nations already have poverty rates that are too high.

However, Jordan has taken active steps in collaboration with the World Bank and the UK government to create jobs for Syrian refugees and low-wage workers through “enterprise zones”.

The idea, announced by the World Bank, is to create incentives for companies to invest in specific areas and employ refugees and the low-cost local workers that refugees often undercut. If the UK-World Bank plan is successful, it’s hoped the European Union will offer similar incentives to European companies.

A solution is desperately needed. According to a new report by the World Bank and United Nations High Commission for Human Rights, titled The Welfare of Syrian Refugees: Evidence From Jordan and Lebanon, nine out of 10 Syrian refugees living in Lebanon and Jordan are in poverty.

The report also mentions that economic conditions in Syria in the years leading up to the civil war meant the people that fled to Lebanon and Syria were already “on the move,” poor and younger than the rest of the population.

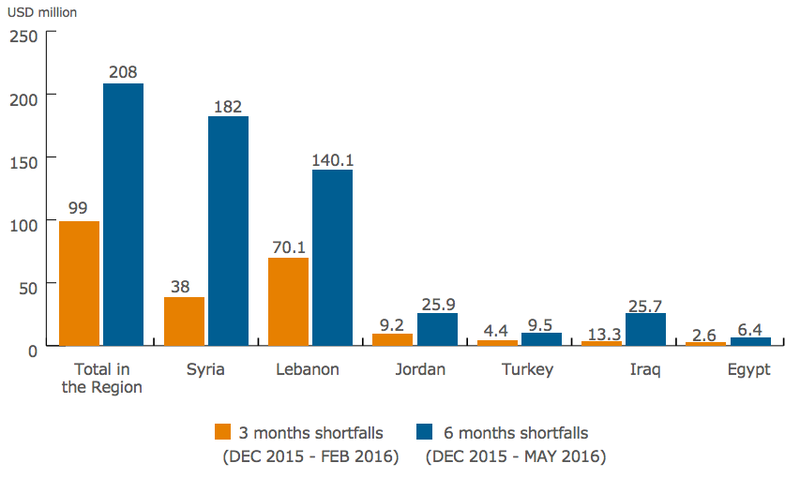

Today, these refugees predominantly rely on a system of voluntary donations that provides short-term cash and food assistance. But, as is evident in this graph which details the projected budget shortfalls for the World Food Program in countries with Syrian refugees, demand outstrips supply.

Such shortfall means that only the neediest refugees get support. The World Bank-UN report says the system is “effective” for those that receive full assistance, but it’s also “not sustainable”. At some stage, the funding will dry up due to lack of support or another humanitarian crisis that demands attention.

With a political solution in Syria that would allow refugees to return home still looking years away, refugees in Lebanon and Jordan continue to rely on a pool of voluntary donations that is too small, and that will inevitably get much smaller at some stage.

“These programmes must therefore be paired with medium- and long-term policies and programmes that allow refugees and host communities alike to benefit,” the report says.

The benefits for the host communities are crucial because the need for refugees to work is not the priority of these host nations, and for good reason.

While nine out of 10 refugees in Lebanon and Jordan are considered in poverty when you take into account the poverty rates of both countries, 28.6 per cent and 14.4 per cent of Lebanese and Jordanians respectively are at or below the poverty line.

So competition at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder in Lebanon and Syria was fierce even before the Syrian refugee crisis came along. What’s happened is that Lebanon and Jordan have maintained or even increased certain obstacles for Syrians to find work, in part, to defend locals who are in need of work.

Earlier this year, Lebanon introduced rules requiring Syrians entering the country to obtain visas before they could move freely. Meanwhile, the process for renewing residency permits has become practically impossible for many applicants.

Unless they can provide a company sponsorship, which is very rare, Syrians have to provide a number of documents, including a signed pledge not to work and a rental agreement from their Lebanese landlord. If they can’t, they can be arrested and detained.

This is the kind of problem these “enterprise zones” would aim to address.

Some of the reasons why Syria’s refugees are in poverty in such vast numbers have been laid out by the World Bank-UN report.

They’re disproportionately young, often poorly educated and originally from rural areas. This is due to economic factors in Syria before the outbreak of the war.

In the early 2000s, the Syrian government undertook a series of reforms to diversify the economy away from petrochemicals.While these efforts were successful, the benefits were predominantly felt by the wealthy and the slide in economic growth between 2004 and 2010 contributed to a youth unemployment rate of 19.2 per cent, almost four times the average for adults.

Combined with a spike in the cost of oil, food and agricultural products and a drought in the years leading up to 2011, it meant Syria already had a large population of people that was young, recently poor and increasingly rural at the time the civil war erupted.

The conflict disproportionately impacted the areas where these already disadvantaged people were living, forcing them to move again; this time, outside the country.

Comments (0)