By Tom Verde, originally published as ‘Malika III: Shajarat Al-Durr‘ on AramcoWorld. Artwork by Leonor Solans.

From Bangladesh to Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan to Nigeria, Senegal to Turkey, it is not particularly rare in our own times for women in Muslim-majority countries to be appointed and elected to high offices—including heads of state. Nor has it ever been.

Stretching back more than 14 centuries to the advent of Islam, women have held positions among many ruling elites, from malikas, or queens, to powerful advisors. Some ascended to rule in their own right; others rose as regents for incapacitated husbands or male successors yet too young for a throne. Some proved insightful administrators, courageous military commanders or both; others differed little from equally flawed, power-seeking male potentates, and they sowed the seeds of their own downfalls.

This series presents some of the most notable historical female leaders of Muslim dynasties, empires and caliphates.

Our third story is that of Shajarat al-Durr, the first woman to sit upon an Egyptian throne since Cleopatra, nearly 1,300 years before.

Little is known about her origins, including her given name and her year of birth in the early 13th century. The name she was known by, “Shajarat al-Durr” (“Tree of Pearls”), is said to have been inspired by her fondness for the jewel of the sea. Legends say she came from royal Arab stock, but historians agree she was most likely born in present-day Armenia to a family of nomadic Kipchak Turks, known to Western medieval chroniclers as “the blonde ones” and among whom women often held high status. “I have witnessed in this country a remarkable thing, namely the respect in which women are held by them,” recalled 14th-century traveler Ibn Battuta.

Around the time of Shajarat al-Durr’s birth, Mongols were sweeping west across Asia, absorbing some Kipchak tribes and settlements while displacing and dispersing others. Some were taken captive and sold to other peoples—including the ruling Ayyubids of Egypt. Shajarat al-Durr’s first husband, Sultan Al-Malik al-Salih, in fact, was the first to bring large numbers of Kipchaks to Cairo. The men became military servants, known as Mamluks, while Shajarat al-Durr, like other women, entered the harem.

In his history of the Egyptian Mamluk sultanate, Cairo-born Al-Makrisi, a biographer, historian and poet of the 14th and 15th centuries, wrote that the sultan “loved her so desperately that he carried her with him to his wars, and never quitted her.” In 1239, she bore a son, Khalil, and in 1240, Shajarat al-Durr and the sultan were married. This freed the bride of servitude, but their son died in infancy, and she bore none further.

Al-Salih, however, already had a son in southeastern Turkey, the troublesome Turan Shah, a child by his first wife. As a result, al-Salih relied greatly on his wife, whose Kipchak roots aided the Ayyubid sultan in mobilizing Mamluk troops to task—first in maintaining his immediate domain, Egypt, and then in extending dominion into Syria. It was this, “her ability to counsel her husband on matters of the state, including military campaigns,” that has garnered Shajarat al-Durr the most attention from biographers today, says historian Mona Russell of East Carolina University and author of Creating the New Egyptian Woman (2004). Writing not long after Shajarat al-Durr’s own lifetime, one Syrian chronicler called her “the most cunning woman of her age.”

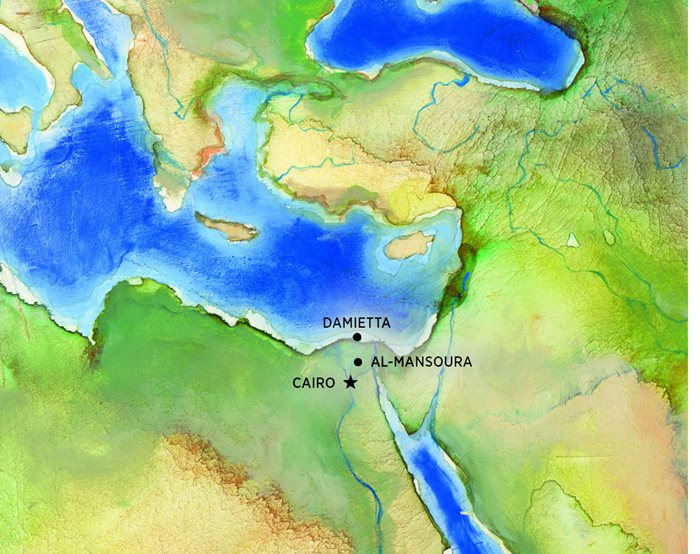

Her acumen became widely apparent in the spring of 1249. Sultan al-Salih, campaigning in Syria, learned that the armies of the Seventh Crusade, led by Louis ix of France, were sailing for Egypt, aiming to land 1,800 ships and 50,000 men in the Nile Delta city of Damietta. Shajarat al-Durr, acting as regent in Cairo, dispatched al-Salih’s top commander, Fakhr al-Din, to Damietta while she led the Mamluks in garrisoning Cairo.

Then came more bad news: The sultan had been wounded in battle. He was on his way back to Egypt by stretcher.

Louis landed at Damietta on June 6, 1249. Overwhelmed, the outnumbered Muslim troops abandoned the city, reported the 13th-century historian Ibn Wasil. They regrouped on the east bank of the Nile, about 100 kilometers northeast of Cairo, at al-Mansoura. There, the ailing al-Salih arrived, and he was joined at his bedside by Shajarat al-Durr. By late August, al-Salih’s health began to deteriorate with each passing day. Ibn Wasil described the situation as “a disaster without precedent … there was great grief and amazement, and despair fell upon the whole of Egypt.”

In November, Sultan Al-Malik al-Salih passed away. Bereaved yet determined to ensure the continuity of her husband’s dynasty and avoid revealing weakness to the Crusaders, Shajarat al-Durr recalled Turan Shah from Turkey and, until his arrival, arranged to conceal the sultan’s death.

She summoned Fakhr al-Din and al-Salih’s head eunuch, Jamal al-Din, who was in charge of the Mamluks, “to inform them of the death of the sultan, and to request their assistance in supporting the weight of government at such a critical period,” wrote Al-Makrisi.

Their deception required an elaborate conspiracy. All orders from the sultan were in fact signed by Jamal al-Din, who forged his master’s signature. (Other sources say Shajarat al-Durr had al-Salih sign batches of blank documents before he died.) A doctor was also let in on the secret, and he was seen visiting the sultan’s chamber daily.

Meals were brought to the door and tasted while singers and musicians performed outside the chambers. Meanwhile, Shajarat al-Durr arranged for a boat, and disguised in black robes, she accompanied her husband’s body under cover of night up the Nile to Roda Island south of Cairo, where the Mamluk troops were stationed. There, she hid the corpse and issued orders—also forged—for construction to begin on al-Salih’s mausoleum.

In this way, for nearly three months, Shajarat al-Durr secretly directed the sultanate. Although Fakhr al-Din fell in battle, his forces began to repulse the Crusaders, and Turan Shah arrived in time for the defeat and capture of Louis.

Yet as successor to his father, Turan Shah quickly began making missteps. “He had no confidence but in a certain number of favourites, whom he had brought with him from [Syria],” Al-Makrisi recorded, and this sidelined the Mamluks.

He demanded that Shajarat al-Durr hand over both his father’s treasure and her own jewels and trademark pearls. “The sultana, in alarm, implored the protection of the Mamluks,” reported Al-Makrisi. They were only too glad to come to her aid, considering “the services she had done the state in very difficult times” and the fact that Turan Shah was “a prince universally detested,” and Turan Shah was slain on May 2, 1250.

The Mamluks decided that “the functions of Sultan and ruler [of Egypt] should be assumed by Shajarat al-Durr,” Ibn Wasil recorded, adding that “decrees were to be issued at her command and … [from] that time she became titular head of the whole state; a royal stamp was issued in her name with the formula ‘mother of Khalil,’ and the khutba [Friday sermon] was pronounced in her name as Sultana of Cairo and all Egypt.”

Although—to recall Ibn Battuta’s observations—the Mamluks were not unaccustomed to female potentates, she was entirely up to the job, “endowed … with great intelligence” and capacity for “the affairs of the kingdom,” noted Khayr al-Din al-Zirikli, a modern biographer and poet from Syria.

One of her first acts as sultana was to conclude a treaty with the Crusaders that returned to Damietta and ransomed Louis ix. These terms she negotiated with her French counterpart, Queen Margaret of Provence. Thus the Seventh Crusade ended with the diplomacy of two queens—one Muslim and one Christian.

Not all supported her. The most stinging objection came from Baghdad, where Caliph al-Musta’sim is said to have declared: “We’ve heard that you are governed by a woman now. If you’ve run out of men in Egypt, let us know so we can send you a man to rule over you.” Wary of the far reach of Abbasid influence, the sultana and her council knew they needed to capitulate if they were to ultimately endure.

So, after 80 days of titular rule, Shajarat al-Durr married and relinquished her title to a minor Mamluk officer, Izz al-Din Aybek, who “had nothing to say,” observed one contemporary. She insisted Aybek divorce his first wife, Umm ‘Ali. Although that command proved fateful, for the next seven years “the power of decision and administration” remained in her hands, as contemporary historian Ibn ‘Abd al-Zahir noted. She signed all royal decrees, dispensed justice and issued commands.

She made her marks culturally, too. She is said to have instituted a nightly entertainment at the Citadel that featured acrobatics by torchlight to the rhythms of music. Popular legend also credits her with founding the tradition of the mahmal, a decorated palanquin on the back of the lead camel in Egypt’s annual pilgrimage caravan to Makkah—a tradition that survived into the mid-20th century.

By 1254 Aybek began to tire of his nominal role. He quaashed a rebellion or two and fought bitterly with Shajarat al-Durr over al-Salih’s treasure, which she kept hidden. In 1257, seeking to increase his power, Aybek took a second wife, a daughter of a powerful prince. To Shajarat al-Durr, this was treason against both queen and sultanate. Aybek moved into a pavilion by the polo fields.

On April 12 he received an apologetic summons from Shajarat al-Durr. Arriving at the palace fresh from a polo match, Aybek was greeted by the swords of the sultana’s eunuchs.

She claimed Aybek had died in his sleep, but this time the Mamluks refused to protect her. Accounts say she passed several days under arrest in the Citadel, grinding jewels and pearls to dust. Aybek’s 15-year-old son Al-Mansur Ali—son of the jilted Umm ‘Ali—succeeded as sultan. He offered Shajarat al-Durr up to the justice of his mother, who had her former rival “dragged by the feet and thrown from the top” of the Citadel, according to 15th-century historian Ibn Iyas. Her remains were interred in the tomb she had commissioned for herself, one of Cairo’s most exquisite. Its mihrab, or prayer niche, is decorated in Byzantine glass mosaics, the oldest in the city, and its centerpiece is a “tree of life,” adorned with pearls.

To this day she remains one of Egypt’s most popular historical figures and, as such, she has been many things to many people. To Western historians of the Crusades, she was incidental. To medieval Muslim chroniclers, she was a respected ruler who shrewdly negotiated an end to the Seventh Crusade and brokered the transition of two great dynasties—the end of the Ayyubids and the beginning of the Mamluks. With “outstanding talents … realized through crisis, and frustrated by law, tradition, and brute force,” as American University of Cairo scholar Susan J. Staffa contended, her story remains today “a woman’s story from first to last.

Enjoyed the piece? Read the the first and second part of this series presenting the most notable historical female leaders of Muslim dynasties, empires and caliphates here.

Art direction for the “Malika” series is by Ana Carreño Leyva. Calligraphy is by Soraya Syed. The logo graphics are produced by Mukhtar Sanders (www.inspiraldesign.com).

Comments (0)