Change begins in the bedroom— controversial, but true. Since the Arab Spring in 2011, there has been an increase in discourse over a sexual revolution and a call for women’s rights. Whether it’s women being arrested for “inciting debauchery”, the prevalence of female genital mutilation (FGM), a lack of sexual education and health, or Egypt’s rife sexual harassment rates, it is becoming more and more evident that Egypt needs a sexual revolution.

The term, ‘sexual revolution’, is commonly used to refer to the movement of sexual liberation in the West during the 1960s. During this period, there was a shift in attitudes towards traditional sexual morality; this included attitudes towards premarital, extramarital, and homosexual relations, pornography, sex education, birth control, and other related topics.

However, as we all know, Egypt is not a Western country, nor should it have to be, to be able to achieve a sexual revolution. Instead, we must look at a sexual revolution in Egypt through a lens appropriate to its historical, religious, and cultural context. The pillars of this sexual revolution, must lie fundamentally in the establishment of proper sexual education and expression, in order to catalyse attitudinal change.

We can see the importance of this through the example of the West’s sexual revolution – despite undergoing a sexual revolution, the West is somewhat an inherently misogynistic framework, objectifying women. Thus, the sexual revolution in Egypt must not take on these forms of imitating Western sexual attitudes.

Shereen El-Feki writes about this in her book, Sex and the Citadel: Intimate Life in a Changing Arab World. Instead of implementing Western ideals of sexual revolution, El-Feki emphasises the importance of establishing sexual rights in Egypt due to their unavoidable connection to gender values and equality.

But what do all these terms mean? What is a sexual revolution? What defines gender equality? The answer is complex, but, El-Feki tries to break this down by using a working definition of sexual rights from the World Health Organisation (WHO) explaining it as:

“The freedom to access sexual and reproductive health services and to generate, share, and consume ideas and information about sexuality…to choose your own partner and to be sexually active, or not, in consensual relations… to decide whether you want to have children, and when… to control your own body and the liberty to pursue a satisfying, safe, and pleasurable sexual life. And all this without coercion, discrimination, or violence.”

To achieve a sexual revolution and reach gender equality, sexual rights must be established as a human right. This is because sexual values are very closely linked to harmful cultural attitudes such as FGM, domestic violence, and their impact on economic empowerment. While to some this may be obvious, to others, it is not.

Before I explain this link, let us first look at Egypt’s current state. When it comes to women’s standard of living, Egypt has consecutively fallen short. In the 2017 Global Gender Gap Report, Egypt ranked 134th out of 144 overall- placing 99th in health and survival, 119th in political empowerment, 104th in educational attainment, and 135th in economic participation and opportunity.

Regarding sexual rights, abortion is illegal, FGM remains prevalent, and 99.3% of women face sexual harassment. These measurements lay the groundwork for where issues are most present as well as giving a general indication of Egypt’s current state of gender inequality. However, they cannot fully reflect cultural attitudes and everyday lived experiences of women. That’s why it is important to discuss other issues, such as attitudes around sexuality.

Shifting Attitudes on Purity and Sexuality

Recently, the phrase “the personal is political” has been used by many activists and everyday social media users. This idea is not isolated to just the West- in fact, for Egyptian women, their personal life is often where politics projects itself the most. Certain attitudes, can have a huge impact on women, particularly those relating to their domestic and sexual life.

For Egyptian women, sex and shame come hand in hand due to “purity culture”. Egyptian feminist and author, Mona El-Tahawy, describes this term as “the religious right’s rhetoric that stresses virginity and modesty as the way for women to attain ‘purity’”. El-Tahawy argues that the existence of this culture burdens women with “the responsibility for their own safety from sexual violence, and for ensuring they don’t “tempt” boys and men”.

Purity culture exists in Egyptian media, social interactions, and within the workplace. While not representative of Egyptian cultural attitudes as a whole, an example is many prominent figures, some religious, who appear on TV drawing parallels between women and objects to be protected, such as diamonds, or even the one saying all Egyptian women have heard:

“Women are like sweets, if you see one that is covered and one that is unwrapped and dirty, which one would you pick?”

This is just one of many things we hear, and are ingrained into our minds from a young age. For a sexual revolution to occur, we need to begin shifting cultural attitudes on how women are perceived, by men, and women alike. Rather than perceiving women as commodities to be protected, they must be considered as beings with agency.

One obvious issue directly related to purity culture, despite its illegality as of 2008, is the prevalence of FGM, or tahara. The practice is undergone in order to suppress female sexual appetite. The 2015 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) showed that 92% of Egyptian women between the ages of 15 and 49 have been subjected to FGM. FGM is a danger to women, sometimes even a fatal one. There are often also irreversible health issues, as well as mental and emotional damage.

FGM blatantly tells us what we already know– sexual pleasure is sinful for women, but a natural urge for men. But, it also serves as an example of how sexual education, along with laws pertaining to sexual rights, can move towards diminishing harmful practices. The DHS survey shows that FGM has declined from 74 percent to 61 percent since becoming illegal in 2008, as well as a shift in attitudes. In fact, the percentage of mothers intending to circumcise their daughters has declined from 92 percent to 35 percent.

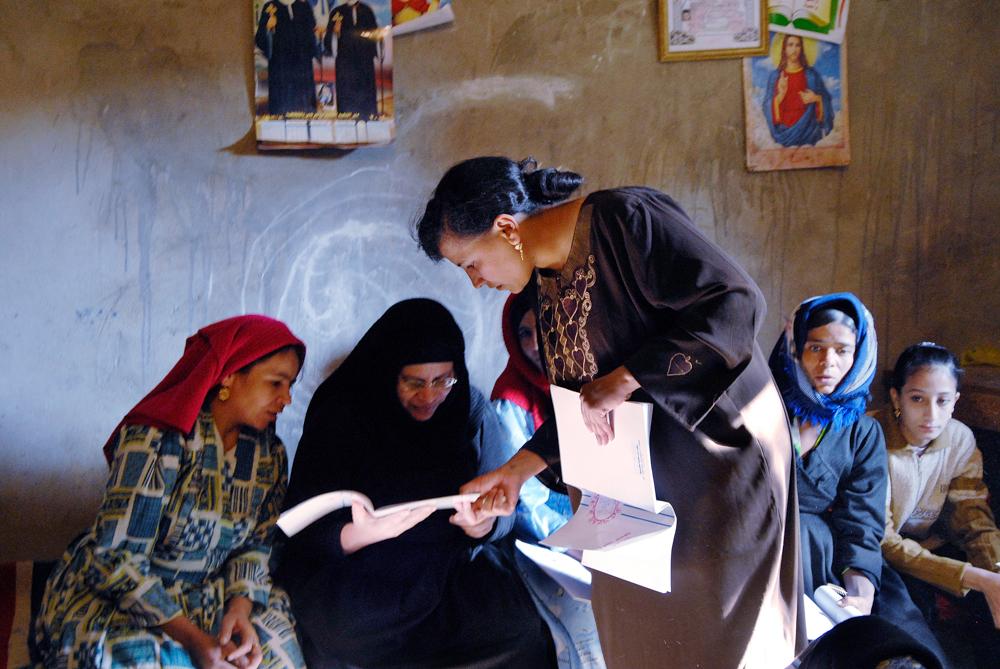

While the criminalisation of FGM instigated its decline, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) explains that the FGM Programme, done in partnership with institutions such as the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, Al-Azhar University, and Dar El Iftaa’ played a crucial role in attitudinal change through its several campaigns utilising media, as well as denouncing the practice within communities.

The link between sexual education and achieving gender equality here is more than clear. The decline of FGM implies that there is potential for education to shift attitudes on other issues such as domestic and sexual violence.

Attitudes and Economic Empowerment

Purity culture not only affects the woman’s wellbeing, but is also closely weaved with women’s economic empowerment. As noted earlier, there is a culture of ‘protecting’ the woman; in order to be ‘protected’ the woman is often subjected to curfews, not being allowed to work by her husband or family.

While this is rooted culturally and religiously, the aftermath of colonialism contributes greatly towards this mentality. It is crucial that if a sexual revolution were to occur in Egypt, it must take a post-colonial framework.

Sex workers (which were once legalised in Egypt during the British occupation) became symbols of decadence, social decay, urbanisation, and exploitation inherited from Western colonial control. Not only did this victimise and demonise sex workers, it also impacted the collective group of working women in urban spaces as their sexuality was considered to be a threat. Women were accused of flirtatious behaviour and dressing promiscuously, leading to a shift in attitudes of husbands forbidding their spouses from being able to work.

The exploitation and exoticisation of Egyptian women by British soldiers induced an enduring humiliation for Egyptian society, instigating some Muslim communities revert to conservative Islamic fundamentalism. Many of these attitudes remain today and women remain discouraged and often vilified for working in public spaces.

Over half of Egyptians surveyed in a 2015 national poll rejected the notion of women in the public sector such as judges, mayors, and president. A contemporary issue that draws upon the link between the domestic and the economic is the implications of abusive marriages and economic opportunities.

Additionally, a third of Egyptian women are subjected to domestic violence with 10 percent of married women also experiencing sexual abuse. It’s important however, to recognise this as not just an attitudinal issue, but also a legal one.

A national survey showed that a third of people in Egypt found domestic violence to be justified if a woman refuses sex or goes out without her husband’s permission, and at the same time, no specific law covers domestic violence or marital rape. Additionally, divorced women are shamed and are often encouraged to remain in abusive relationships by male family members.

Furthermore, psychological studies have shown that women facing intimate partner violence (IPV) are less likely to engage in economic engagement, and are more likely to invest their time in domestic labour as they bargain with patriarchy.

Under classic patriarchy, women are married at a young age and become subordinate to the men (the husband) and the senior women in the house. To ensure and maximise their security, the young women will conform to what is expected of them (domestic duties rather than market participation) so that eventually they can inherit the authority of senior women while simultaneously internalising patriarchy.

Given the importance of marriage in Egypt, with over 90 percent of Egyptians considering it the desirable and natural state, it’s clear that a shift in these attitudes, shaped by a sexual revolution is key to achieving healthier married life. This in turn, would lead to higher women’s economic participation, bridging a gap of inequality both in the bedroom, and outside. In bridging this gap, the Egyptian economy and society benefits as a whole.

What Now?

In order to work towards achieving gender equality, a sexual revolution, rooted in the basis of sexual rights is necessary. Whereas the Western sexual revolution took place entirely detached from religion, Egypt’s postcolonial position means religious influencers play a larger role in societal attitudes, in addition to popular culture and media.

This means that for a sexual revolution to occur, religious institutions must be included in normalising sexual education and breaking taboos.

Of course, the sexual revolution on its own is not enough to cross these barriers, there are numerous unconsidered intersecting factors such as political instability, accessibility, and poverty. However, given the way in which sexuality is at the core of issues such as FGM, domestic violence, and economic empowerment, it is appropriate to claim gender equality cannot be achieved without a sexual revolution.

This is because sex is esoterically involved in the intricacies of everyday personal and public life. The misinformation about sexuality maintains a power imbalance whereby women remain marginalised.

So long as there is ignorance, attitudes will never change; therefore, any stride towards gender equality will only be on a superficial basis, as the fundamental socio-cultural beliefs will not have reformed.

Comment (1)

[…] Source link […]