Stepping into the colorful and spacious hub of Cairo-based social enterprise Thaat and its sister company PAZ.Cairo, an ethical fashion brand that pays homage to traditional craftmanship, is certainly a unique and worthwhile experience.

“Here, customers can come and be made to feel like a princess, have a nice drink, sit down and have measurements taken,” explains Peri Abuzeid, founder of the joint venture.

In fact, this is a key reason why their products are only delivered internationally, and not locally.

“I’m actually doing this on purpose. I want people to come to the store and experience the whole story. It makes a big difference.”

Much of the conversation that Peri kindly agreed to have with Egyptian Streets, about the multiple facets of her work and the inspirational backstory to Thaat, ends up taking place in the store-section amidst beautiful racks of clothing made from carefully-sourced Egyptian textiles and boasting exquisite details such as handstitched embroidery or beading.

As we observe and feel our way through the different designs on display, details about the production process, the artisans and ultimately, the business as a whole, begin to unfold.

“This is the store, where we sell our label PAZ. It’s a separate venture from Thaat, and came three years later,” Peri explains, adding that the clothes are made partially by “Thaat women” and different artisans.

Many of the garments in fact start off in the hands of men, who are embroiderers or master tailors. “Once their part is done, they bring it to us. We finish it off, we iron it, we add the label, we add extra embroidery, for example.”

As such, the precious artisanal pieces pass through multiple hands and go through many stages, ultimately justifying the price tag, a core part of Thaat’s work ethic being to pay fair wages to their artisans.

Thaat is an Egyptian design and social enterprise that aims to empower local artisans and emerging designers through holistic and tailored solutions that combine design-thinking with research and development. The enterprise comprises three main elements.

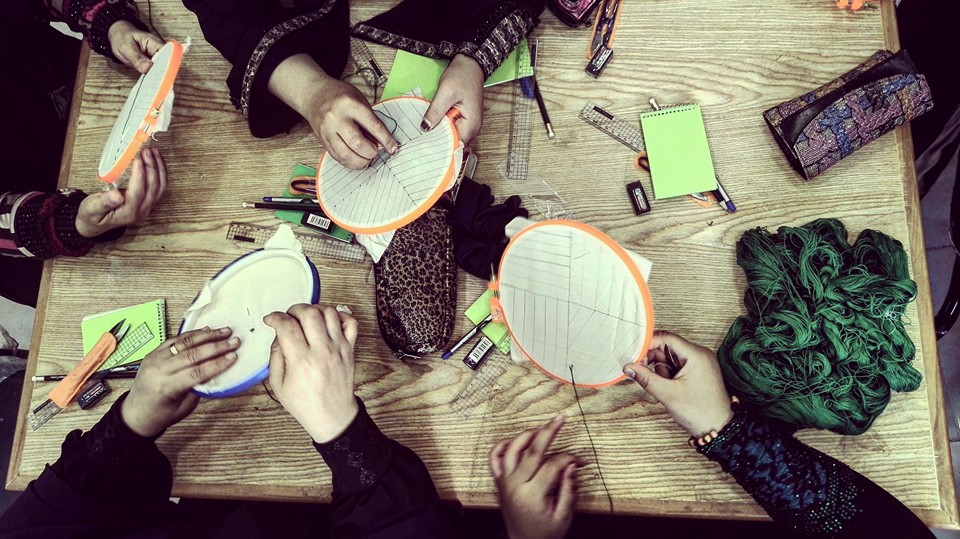

Firstly, it is a mobile design and handicraft school, which works with marginalized women, especially women and girls.

“Women and girls have more discipline in craft business,” Peri explains, and this is why she makes them central to her vision which, more broadly speaking, is to “raise their awareness and confidence to be decision-makers.”

What she means by decision-makers, is that ultimately they would know how to independently source materials, know the difference between mass production and niche markets and thus be able to clearly position themselves.

“In the workshop we have one refugee, Fatima, she’s from Yemen,” Peri describes as an example. “Fatima is very aware, she can multitask, she becomes a hybrid artist who understands what excellent products are.”

Secondly, Thaat is also a consultancy, in that it offers training through working with local civil society as well as international institutions.

Its third element is the ethical pret-a-porter brand PAZ, which revives Mamluki tailoring and embroidery techniques and is sold in the store next to the workshop space.

Describing the brand, Peri explains that it reflects “a combination between the contemporary and the traditional cuts – we try to create something new.”

Along the racks we find garments that will likely suit a variety of tastes and age-groups, ranging from elegant kaftans to more plain pieces, the prices of which are adapted accordingly. There are also beautiful high-waisted trousers and a men’s collection will soon be launched, which shall comprise shirts and jackets.

“The nice thing about our stuff – of course you wouldn’t wear them every day – but if you have a nice meeting, you can tone it down. It’s casual chic.”

85-90% of the fabric they use is Egyptian, either bought from big suppliers or from their own two weaving looms in Upper Egypt. Yet unfortunately, good quality textiles are not easy to source locally.

Sharing stories about some of the interesting exchanges that have taken place between designers and artisans in and outside of Egypt, Peri emphasizes her collaborations with artisans from Upper Egypt, whom she visits and sources when travelling around the area.

Pointing to a dress featuring the traditional embroidery technique ‘talli’, she explains that “we usually order them as a piece of fabric that is embroidered, and we finish the piece according to our own designs. The women trust us, we have a very good relationship with them.”

“We try to help and work with different artisans by ordering from them and integrating it into the collection as you can see.”

It is therefore not surprising that all these beautiful textiles have their price, a reality that can pose difficulties for the brand, especially with the market recently not being as enabling as desired.

“Buying textiles for a collection, we are talking something between 40’000 to 60’000 EGP. And this is just the textiles, not the salaries or extra beading work that is done.”

While Thaat won a prize from Barclays Social Innovation Facility (SIF) back in 2013, which allowed for investing around $5000 in necessary machinery and raw material, the rest has since all been self-funded. Whatever profit is made, is then re-invested in the social enterprise, allowing them for instance, to launch phase one, which includes the store and workshop space we visited on Soliman Abaza street in Dokki.

The Road to Thaat

Once we settle down for tea, Peri tells us more about the inspiring and fascinating journey leading up to the opening of this space, a space that will ultimately require more support and foot-traffic in order to survive.

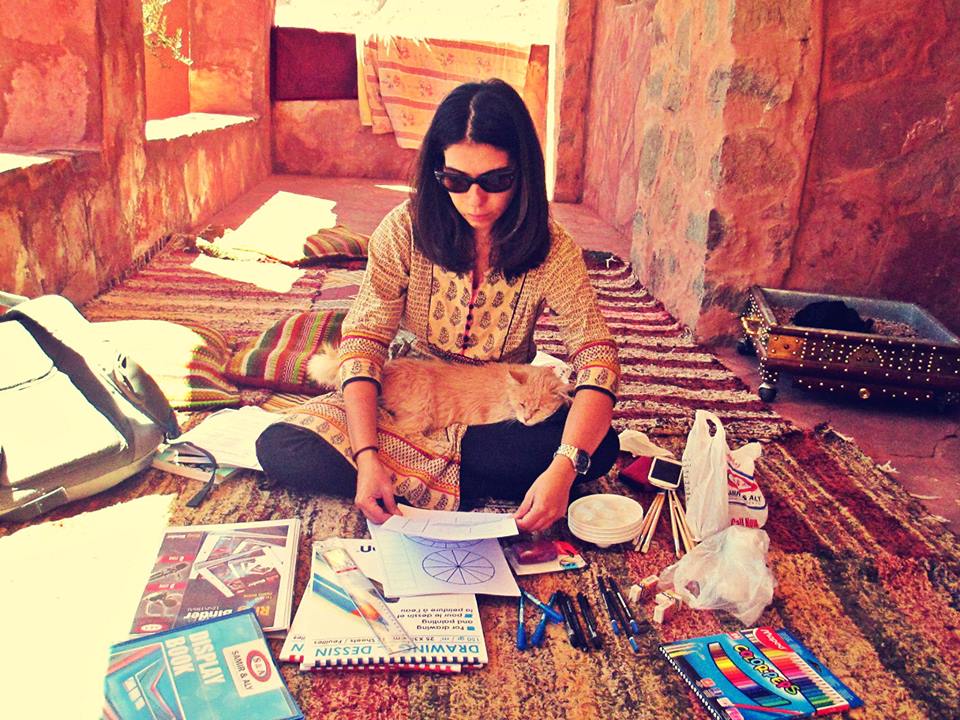

Dubai-born Peri developed a passion for fashion early on in her life and was always keen to learn more about her country’s heritage in the realm of crafts and artisanry, particularly crafts produced by marginalized communities. She tells us how she has always felt that there is more important work to be done than simply designing and selling clothes.

Having initially taught arts and crafts in an international school for seven years, she was soon encouraged to “resign and get out there!”

She did an internship with a local designer who creates gallabiyas, at the end of which she developed her first small capsule collection from that designer’s leftover textiles.

Ever since, she has continued to implement many of her creative ideas and projects with the support of local NGOs or programs such as Vodafone Foundation’s “World of Difference,” which is no longer running.

Furthermore, a number of international exchange and educational experiences, not least a scholarship to study for an MA in Social Entrepreneurship at Goldsmiths College in London, broadened her horizons and introduced her to the countless possibilities out there.

Her studies also exposed her to works by the likes of Dr. Hans Prinzhorn, who has researched and written about ‘outsiders arts’ and the ways in which art can influence the mentally ill; Peri too, would soon start focusing on arts produced by people that face socioeconomic struggles or with disabilities.

“Their arts are often mind-blowing, because they come from an unusual mind and mind activity.”

Peri’s independent research in Cairo involved visiting lots of artisans in the Khan el-Khalili and Gamaliyya districts of Cairo, where she would ask them about their crafts, trade and everyday problems.

This wide range of experiences gradually converged, allowing the aspiring designer to identify some of the core issues faced by Egyptian artisans under contemporary market conditions, pushing her to come up with her own model, which she has since been working on hard and putting into practice in various capacities.

“I came up with a very simple model. Maybe to solve the problems, we need to focus more on the final outcome of the training, to focus on the exit strategy of each project, which means maintaining the sustainability of the effort.”

Having seen that many projects fail since nothing is done once set time frames expire and they are no longer part of an organization’s budget, Peri would focus on precisely that in her second MA degree, an idea that would eventually take shape and become Thaat’s incubation model.

“The idea is to equip women with tools and knowledge that will enable them to continue, even if we leave them – that’s the incubation.”

Since returning from London, Peri has been involved in numerous projects, starting out with a cooperative of women in Helwan. Her most recent project is supported by CARE and UN Women and is called “Al-Mashgel”, which has involved creating a physical space as well as a label, essentially incubating an idea and turning it into reality.

Another successful project was “Studio Imbaba” that was launched back in 2014 and involved establishing a design and handicraft school in the impoverished neighborhood of Imbaba, ultimately producing a successful and hand-made Egyptian fashion line.

Facing the Challenges of the Market

While much of Thaat’s journey unfolded organically, with one successful project paving the way for a next, we also learn from this conversation that conditions have been getting more difficult recently, and opportunities more sparse, as the enterprise has been struggling to attract new projects and at the same time pay fair salaries.

“The market is evolving and changing rapidly. You know, sometimes I’m lost on what sells, you have to keep a close eye. What do people like on Instagram? Our model needs to be fixed again, I don’t know what went wrong,” Peri explains.

“I do have a vision and I already successfully implemented the vision, with a little bit of money. The impact was strong. Why can’t we have an environment that empowers smaller businesses? The reality right now is that the environment is not enabling.”

The challenging part emerges between the start-up stage and the scale-up stage of a business, we are told. While Thaat has built a solid foundation, in order to be sustainable, they need to expand their reach.

Peri concludes our conversation by saying that they are currently focusing on the label and the space, while figuring out new ways to do things – “to attract the attention of people to the quality of work we are doing.”

Judging by our visit, these beautiful garments and the impressive and ethical work that goes into producing them, is a vision worth supporting.

The store and workshop can be visited from Sunday to Thursday (11am – 5pm) and on Saturday (6pm – 10pm). The address is 22 Soliman Abaza Street, Floor One, Flat Two (blue door), Dokki.

Comments (5)

[…] “Thaat”: An Egyptian Design and Social Enterprise With An Inspiring Vision Egyptian Streets […]

[…] To Read More, Please Visit Source […]