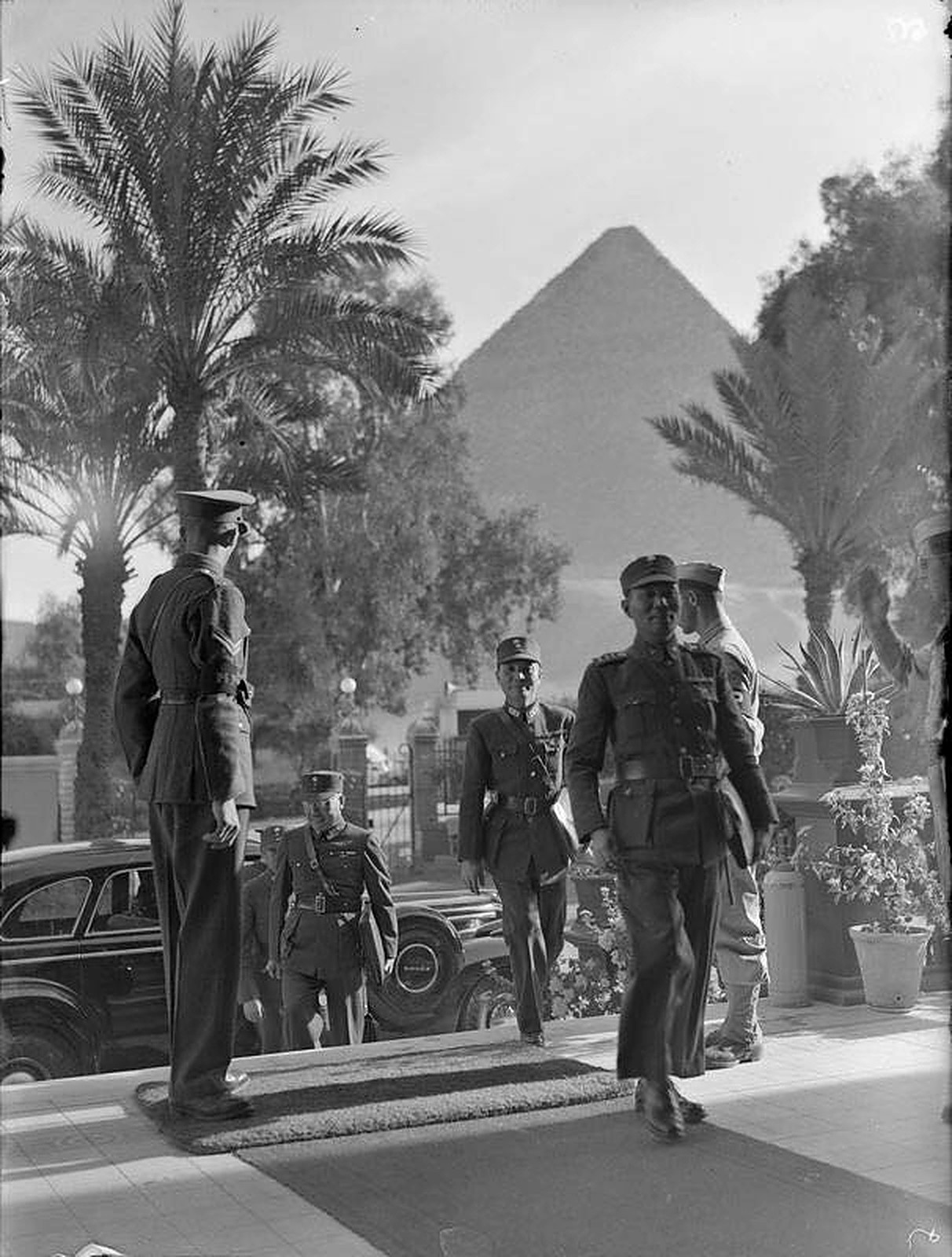

Near the Giza pyramids at the American Ambassador to Egypt’s residency, world leaders from the US, Britain and China met for the first time in 1943 in November and December to discuss peace and plans for the postwar world order. It was a rare occurrence that witnessed the joining of forces between the West and China, and also the draft of Cairo Declaration that changed the history and the world’s political landscape. The Cairo Conference represented the main idealistic vision by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who hoped to create a new global order that would maintain peace and create the hegemonic structure of the United Nations, which is now led by the five permanent powers of the Security Council: China, France, Russia (formerly the Soviet Union), the United Kingdom, and the United States. However, some historians question the successes of this vision, and whether it promoted more unity or hostility in current international relations. BACKGROUND Earlier in 1943, former President of the US Roosevelt and former President of China Chiang Chungcheng (also known as Generalissimo Chiang) expressed a mutual desire for a personal meeting in the autumn to ascertain…

The 1943 Cairo Conference That Shaped the Global Order Post World War 2

September 13, 2019