When it comes to cultural exchange between Egypt and Israel, it is usually boiled down to the controversy of normalizing relations with a state that is guilty of war crimes and illegal annexation of Palestinian territory.

While boycott can be an effective strategy in shedding light on injustices, and carries empathy towards the struggles of those who are stripped from their rights, it is not yet acknowledged that cultural diplomacy can also play an important role in achieving various other goals, from national security to political peace.

Cultural diplomacy is more than just the exchange of ideas, information, art, and language among different nations; it can also act out as a positive force in spreading a certain political cause by presenting it in a more interesting and understandable form.

In other words, to present a political cause to a foreign audience, one must also present the culture of its people with it in order to create more depth, connection and understanding of the cause.

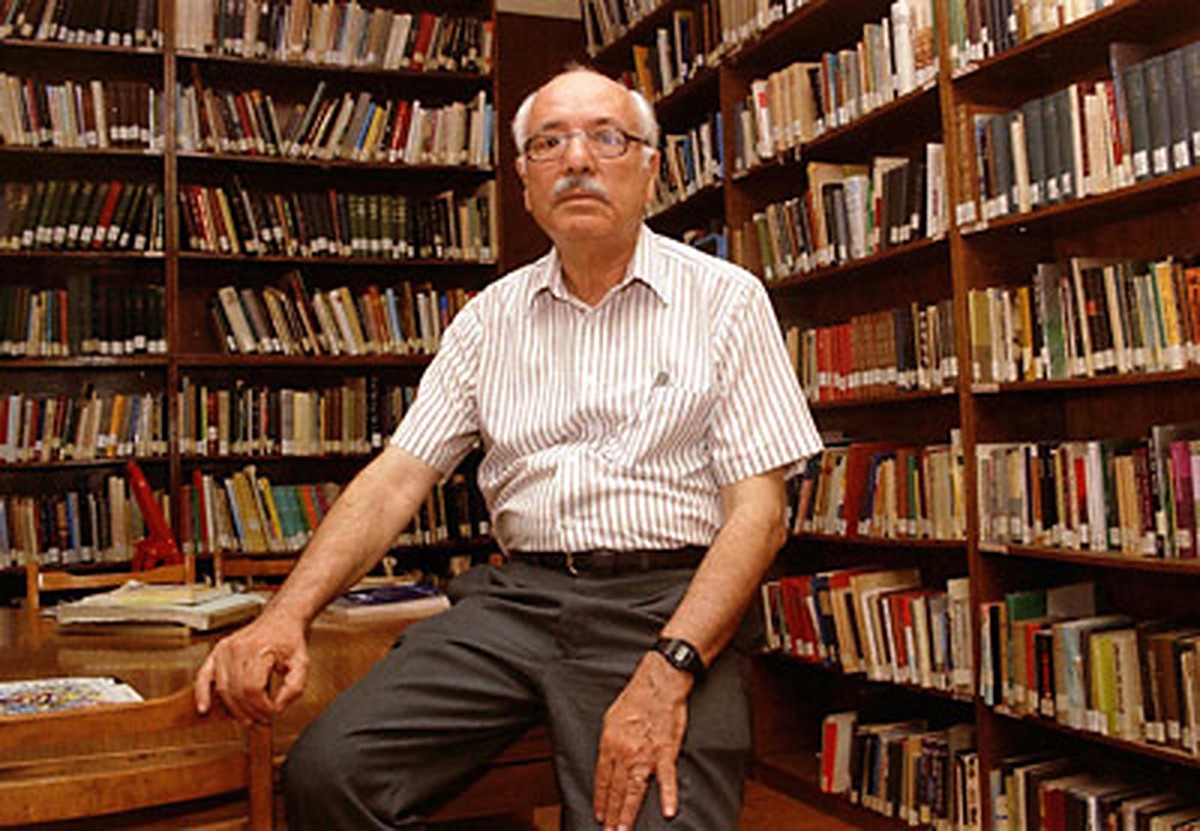

A symbol of good cultural relations is the relationship between Sasson Somekh, who recently passed away August of this year, and Naguib Mahfouz.

Born initially in Baghdad as an Arab Jew, Somekh left to Israel at the age of seventeen and then went on to become an academic, writer and translator in Arabic literature, before doing his doctorate at Oxford on the novels of notable Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz.

While he lived in Cairo and worked as the head of the Israeli Academic Center (1995–1998), which was established following Egypt and Israel’s peace treaty in 1979, he and the Egyptian novelist developed a close friendship that initially began fifteen years ago when Somekh contacted him during his studies. “He alienated all the Egyptian critics by saying the only person who understood him is this Israeli,” Somekh once said.

I first came across Somekh through his article ‘Naguib Mahfouz: Time and Memory’, in which he discussed the problem of memory and how it is represented in different forms in Mahfouz’s novels. I admired his careful categorization of each kind of memory and the clever realization that there is a correlation between the pace of life in these stories and their writing style. What struck me the most, however, is also his attention to the history of Egypt mentioned in the novels, and how literature gave him a chance to understand another society despite the political differences.

This was also the case with Mahfouz, as Somekh recalls in ‘Memories of Mahfouz’ his conversations with the novelist, and the time he brought him the book “The Lover” by Israeli writer A.B. Yehoshua in 1980 in Arabic translation. “He was captivated by the character of Na’im, the Arab mechanic,” Somekh notes, “and asked if it were really possible for an Arab man and Jewish woman to be intimate and if we were really that permissive.”

Mahfouz and Somekh also met frequently at cafes and shared weekly Thursday meetings at his office in Al Ahram newspaper’s headquarters.

In one incident in 1985, Somekh writes that he found 20 young Israelis holding copies of Mahfouz’s novel in Hebrew translation in his office; they were students from Ben-Gurion University and came to ask the author questions about his books.

While they did not often discuss politics or the question of Palestine, the cultural exchange between them still demonstrates how literature can present political matters – such as the perceptions of an Arab in Israel and the political periods in Mahfouz’ ‘Miramar – from a more human point of view, and which can be much more relatable and understandable than the point of view of the politicians.

As a result of this understanding, Mahfouz became the odd one out in his support of the Camp David Accords in 1979, and sent a letter to Somekh expressing his sadness over the wars that happened over the years.

“Our two nations have known fruitful coexistence in ancient times, in the Middle Ages, and in the modern period, while the periods of conflict and dispute have been few and far between,’’ Mahfouz wrote. “But to my great sorrow, we have over-chronicled the moments of conflict a hundredfold more than we have recorded long generations of friendship and partnership.’’

At its core, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict involves a lot of human-related issues such as identity, religion, war, and rebellion, which necessitates the need to read and access more human points of views to develop better understanding.

The situation was no longer the same for Somekh following Mahfouz’s death, as he found himself shunned by other writers, academics and even journalists in Egypt, as the Egyptian Gazette newspaper once stated that the Israeli Academic centre “is only a legal front for Israeli espionage in which Egyptians as well as Israelis are involved.”

“I ask myself, What are we achieving here? Maybe it’s better to close down,” Somekh told Washington Post.

“On the one hand, this is the only example of anything to do with normal relations, with culture, with something other than politics and terrorism. On the other hand, it’s a target for vilification of Israel, for everything against Israel.”

Following Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s election, it is difficult to imagine relations to proceed due to his aggressive plans in annexing more territory and disregard to the Palestinian voice. With little hope of success in peace treaties and negotiations, the only solution that seems to stand in the way is war.

Though perhaps cultural relations can be a relief in the midst of battle – in the midst of the hatred, the killing and the violence, perhaps the human stories of Palestinians can travel through art to Israelis, and vice versa, and create better understanding of each one’s situation.

The opinions and ideas expressed in this article do not reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comment (1)

[…] September 16, 2019 Kimberly Rogers-Brown ISRAEL, Palestinians Leave a comment Link to original article […]