Dancing around the stage, wearing a black leather jacket and a white Spanish-style dress, 29-year-old Madonna was performing her controversial 1986 hit ‘Papa Don’t Preach’ during her ‘Who’s That Girl’ tour in 1987, with the screen in the background showing portraits of Pope John Paul II and then-US President Ronald Reagan. Known for her powerful use of imagery, the performance juxtaposed images of prominent male figures behind her as she jumped around the stage, repeating passionately, papa don’t preach, I’m in trouble deep, papa don’t preach, I’ve been losing sleep.

Like many of her other works, there was a huge confusion around the philosophy behind the song. Released during a polarizing time in the social history of the United States, when conservative religious movements were gaining momentum in parallel with liberal social and cultural changes, the song caused heated debates about its lyrical content, as she declares in the song, I made up my mind, I’m keeping my baby.

Alfred Moran, executive director of Planned Parenthood of New York City, attacked the song in a 1986 New York Times article, saying that the “the message [of the song] is that getting pregnant is cool and having the baby is the right thing and a good thing and don’t listen to your parents, the school, anybody who tells you otherwise—don’t preach to me, Papa. The reality is that what Madonna is suggesting to teenagers is a path to permanent poverty.”

The influence of the song on many young women in America, however, was undeniably immense, as conservative commentator Susan Carpenter McMillan said that teenagers reacted positively to the song’s empowering message. ”These were young girls, 14, 15, 16, living through tough times, going against parents and boyfriends,” she said. “Knowing someone like Madonna is in their corner, saying, ‘All right! Go for it!’ was so uplifting.”

Madonna later clarified her stance to music critic Stephen Holden in the New York Times, saying “that everyone is going to take [the song] the wrong way” and accuse her of encouraging every young girl to get pregnant. “This song is really about a girl who is making a decision in her life,” she said. “She has a very close relationship with her father and wants to maintain that closeness. To me it’s a celebration of life.”

In the music video, Madonna plays the role of a young girl struggling to reconcile the love she has for her father and her boyfriend. Gripped by the tension of wanting to please her father and yet, at the same time, make her own decisions, she chooses to talk to him instead, as she pleads for his understanding and sympathy. After a period of conflict between them, her father eventually accepts her decision, and the final scene is a moment of embrace between the father and the daughter.

What can be inferred from this is that the message of the song is predominantly individualistic, choosing to focus on an individual case – a sympathetic character – rather than a societal issue. In fact, this focus and celebration of individualism is precisely what has drawn a lot of criticism towards the song and the entirety of Madonna’s feminism, as it blurs the lines between what is deemed good and harmful for the community.

Doyle Green, for instance, says in ‘Teens, TV and Tunes: The Manufacturing of American Adolescent Culture‘ that Madonna’s ‘brand of girl power feminism’ can often succumb to narcissism and ‘Material Girl’ capitalism. Academic Yvonne Tasker describes Madonna as an ‘interesting figure’ in Working Girls; at times her work can indeed “question assumptions” in society, at other points, she also “constructs hierarchies which seem content with the production of her as [an] embodiment of white womanhood.”

Deciding on whether she is a feminist icon or a product of a highly individualistic Western capitalist culture has been the essential problem for many feminist writers and academics. In a world where women are victims of domestic violence, female genital mutilation (FGM), and child marriage, an embrace of individualism and the ‘ownership’ of one’s destiny, power and sexuality, as Madonna continually says, seems too far-fetched and detached from the realities of what other women face, and can scream more of white womanhood and privilege rather than feminism.

In other words, how can Madonna’s individualism, and her ‘papa don’t preach’ message, help a young girl on the other side of the world forced by her father to undergo the horrors of female genital mutilation?

In Egypt, violence against women continues to exist in all of its forms, from female genital mutilation, which can happen to 90 percent of young Egyptian women, despite being criminalized by law, to sexual harassment, honor crimes, and domestic violence. While there have been various efforts to combat these crimes, both nationally and locally, their continuing widespread existence points to the depth of the problem, and the need for all agencies to coordinate in tackling it.

As a 22-year-old who grew up watching modern Egyptian films and series, there were times when societal problems, such as a young undergraduate’s pregnancy in the 2003 soap opera Al Hakika Wa Al Sarab (The Truth and the Mirage), were often presented in a way that humiliated the woman and showcase the horrors of shame she brings.

Having a daughter, and growing up as a daughter, becomes the most terrifying thing ever for many parents and girls in Egypt. The honor of the family is deemed more sacred than the parent-daughter relationship, and eventually, it turns to aggression and control over a girl’s body and mind. The deeper the fear, the more the aggression intensifies, resulting in violent practices like female genital mutilation.

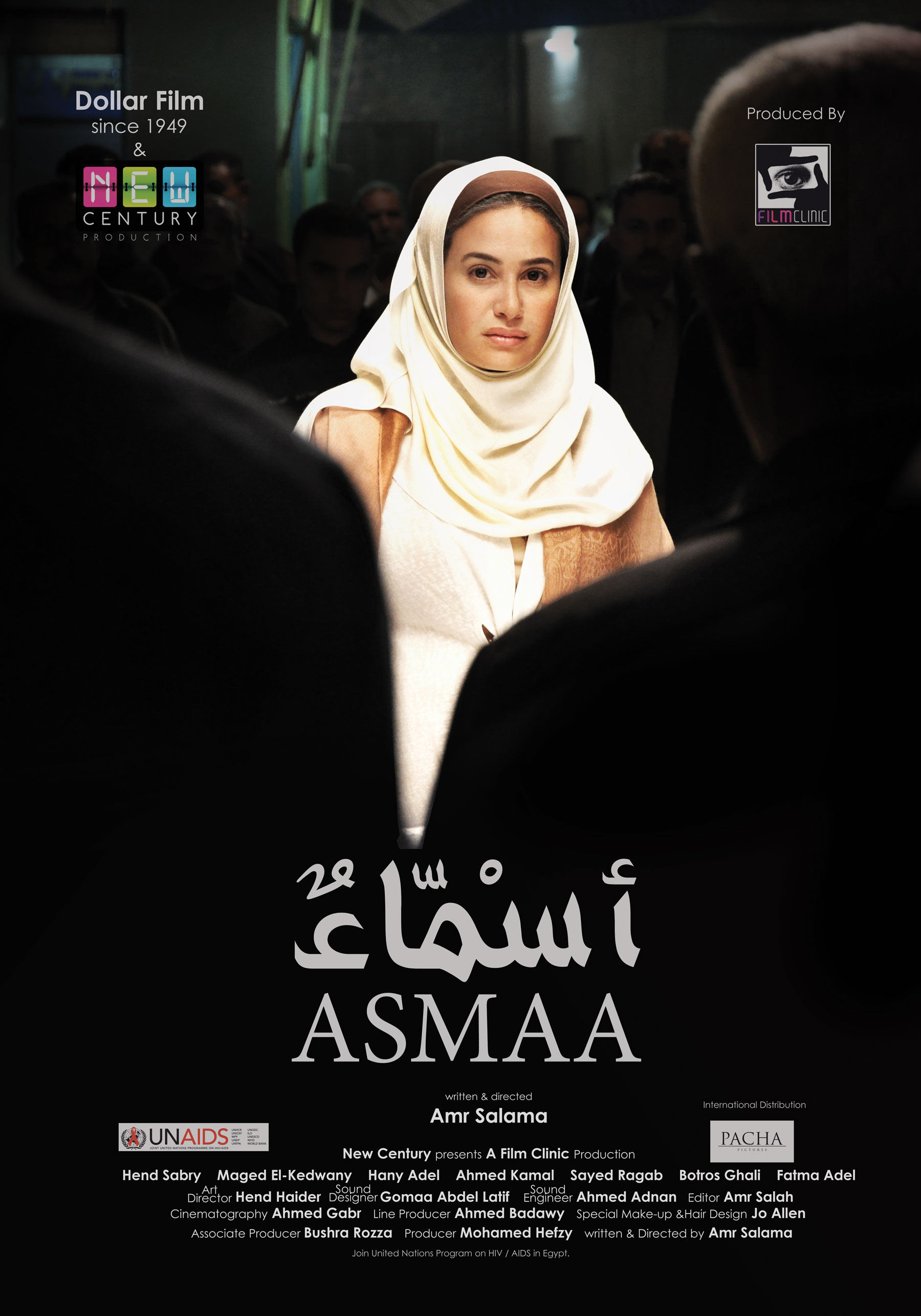

There were only a few times when novelists such as Taha Hussein tackled issues such as honor crimes with more depth and compassion to the female character, like in The Nightingale’s Prayer in 1959, which highlighted the plight of young women in rural Egypt, and the insensitivity and wickedness of male figures. Recent films like Asmaa in 2011, written and directed by Amr Salaama, is also a rare example of a modern Egyptian feature film that presented AIDS patients – particularly a woman – sympathetically.

Last week, when my father overheard me listening to Madonna’s Papa Don’t Preach, he recalled the influence of the song on a small fraction of young Egyptian women like his cousin in the 80s, who was prevented from marrying the man she loves. “She [his cousin] kept repeating the lyrics to her father every time they argued,” he said. “Saying ‘don’t preach to me, baba! Papa don’t preach!”

Yet, for a majority of Egyptian women in the 80s and today, there is no Madonna and no Papa Don’t Preach. Women are often told to listen to authoritative male figures, even if it harms their own lives, body, mind, and spirit. In 2017, it was revealed that 90 percent of men and 71 percent of women consider that wives should tolerate violence to keep the family together.

“When you search online [for] anything related to women’s issues in Arabic, you often always get the opinions of religious clerics first,” a coworker tells me at a women’s center in Egypt. The woman’s own individual experience, and her own thoughts and opinions, are usually never highlighted or brought to attention in the media.

It is this particular individualism that I found important in Madonna’s Papa Don’t Preach song. I prefer to take a more balanced approach and also see the fruits, rather than just the ills, of her work. While some criticisms of her feminism still stand, as extreme individualism can result in the wrecking of the family and community as a whole, the focus on a woman’s voice in the song and the video is what is distinctive and significant.

When Madonna embraces her father in the video, she is giving the female character in the song the power to speak for herself to others. She – the woman, the mother, and the daughter – becomes the author of her own story, and her own life.

Sometimes, she is not always the villain. Sometimes it can even be the man.

It is hard to speak about this kind of individualism to women who have been stripped off from all their individuality. Feminist movements around the world still have a long way to go until they create a form of communication with other women living in underprivileged circumstances.

Yet perhaps the individual stories of women, spoken about in songs like Papa Don’t Preach can slowly change the fabrics of society that shuts down the woman’s voice completely. Perhaps if Madonna had released just this one song in Egypt in the 80s, it would have caused much needed controversy and debate, and created the right kind of chaos that would shake very the ground on which oppression stands.

The opinions and ideas expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comments (0)