There was a time for me when visitors ringing the doorbell was considered to be possibly the best moment – a time for fun gathering and company. I was young and couldn’t care less to prepare the cups of tea, wash the dishes or prepare the meal for around five or more individuals.

It was a task for the other older women in the family: my grandmother, my mom, my aunts, female cousins and just about all the women in the room. It almost felt like it was a natural law. None of the men really objected to helping out, but in actuality, none of them were willing to do so.

They all sat back, relaxed, and smoked their cigarettes, looking busy in their conversations, while a woman gently asked them how many spoons of sugar they preferred or which slice of cake they liked to be served.

At the time, I didn’t see the big issue with it until the role was thrown onto me. I still remember the first time I was expected to serve others and how anxious it made me feel: Am I expected to get up now and serve tea? Who gets up first among the women in the family? Will they hate me if I don’t even get up at all?

Immediately, my value as a woman became connected to a very simple act that was not even thought about or prioritized by the other men in the room. A woman who gets up and serves others is a good woman, a woman who doesn’t is bad.

I dreaded the moment visitors rang the doorbell ever since. Not because of the act of serving others, which is considered to be an embedded value in our culture, named ‘karam’ or generosity, that is directed for both men and women, but because I felt that housework and the way we perceived a woman’s role inside a house was very much unfairly divided.

As Megan Stack notes in her insightful article, ‘housework is a ubiquitous physical demand that has hamstrung and silenced women for most of human history. And yet, it is seldom considered as a serious subject for study.’

For me, the simple fact of being expected, at all times, as a woman in the household to serve others during family visits was the moment I began to feel how deeply rooted, and also invisible, these unexplained and unjust power structures exist in societies.

Now, as the COVID-19 crisis is taking over the world, think pieces like “Women’s Domestic Burden Just Got Heavier with the Coronavirus” and “The Coronavirus Is a Disaster for Feminism,” were shared on my timeline by other friends, and while I shared the same concern, I also questioned: why are we still made to believe that women should do all the ‘housework’?

At this point, shouldn’t more members in the household be more cooperative since everyone is now spending more time at home? Why are we still tied to the idea that it should be only the women in the house preparing meals, doing the laundry and the dishes?

Pushing forward

History tells us that roles in societies change as contexts and attitudes change. Over the last decade, an increasing number of women have gone to work, and the gender pay gap has been gradually narrowing. In 1974, Sweden became the first country ever to introduce a gender-neutral paid parental leave benefit, where both women and men were entitled to 480 days of paid parental leave (16 months) per child.

This way, a month was reserved for each parent to achieve a more even distribution of unpaid household and care work. And it worked, (for the most part, though there’s still a long way to go), making Sweden among the highest female and maternal employment rates in the world as it became possible for both parents to combine work and family life. This was also matched with extensive system of public child care, and most importantly, strong political will through the comprehensive ‘gender equality policy‘.

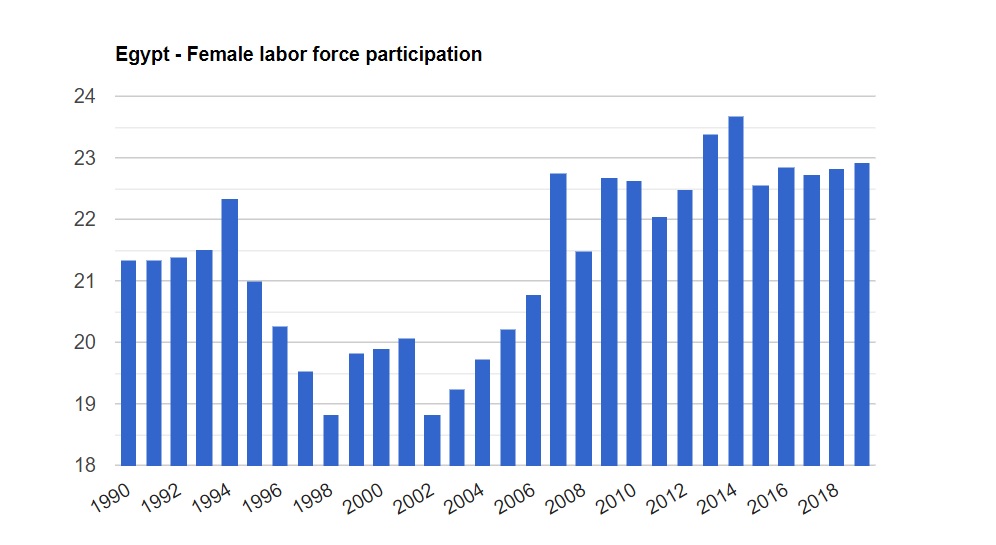

In Egypt, women are entitled to 90 days of paid maternity leave in the private sector and 120 days for workers in the public sector. Employers with 100 or more women in a workplace must also provide childcare facilities, though many resort to lowering the number of women in the workplace on purpose to avoid higher costs of childcare. With little incentives to support women to remain in the workforce, and no policies that recognize that work-family balance measures concern both women and men, women’s domestic burden continues to prevent economies from tapping into the reservoir of female talent.

In collaboration with Gallup, the ILO surveyed men in 2016 on their perceptions of work, which revealed that women’s quest for decent work and employment largely depended on men. In Egypt, when asked whether they prefer for the women to stay at home or work at a paid job, 55 percent said they preferred that the women stay inside their homes, revealing the deep rooted social restrictions that is inhibiting women’s work.

Rather than taking this COVID-19 crisis as a step back for women, or creating the image that women are forever trapped inside the hole of domestic housework, what should be done is turning this into an opportunity to push for more changes.

‘Helping Out’ with Chores?

More Egyptian male friends have started to tell me their experiences of cooperating at home ever since the outbreak, like vacuuming, washing the dishes, and laundry nearly every day. Other women with more males in their households also reflected on the slow changes that can occur when there is a push coming from their side. “At first, it was my mother calling on my brother to help out in the kitchen or other chores, but now we are starting to see him spontaneously doing chores on his own,” says one of them.

Largely, however, these efforts are still confined to ‘trying’ to ‘help’ out in random tasks, rather than actually participating in the entire process of planning and managing the house. In her book ‘Fair Play‘, American author Eve Rodsky made an important point when she highlighted the ‘mental load’ that women carry, as they are the ones that mostly lead and plan out the entire day.

In her book, titled Fed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way Forward, Gemma Hartley defines emotional labor as ’emotion management and life management combined. It is the unpaid, invisible work we do to keep those around us comfortable and happy’. It is the invisible labor that women do which glues a household together that is often overlooked.

On social media, various images of Egyptian men ‘helping out’ in housework were shared widely and sparked a debate. What stood out most for me, however, is the way we praise tiny little efforts that are small and incomparable to the efforts of the mother in the household. Why should we use the term ‘helping out’ when it is also where they reside and not someone else’s property? Sociologist Arlie Hochschild put it in her 1989 book ‘The Second Shift’, where she noted that if a man does just a little more what the average man does in his community, he’s regarded as “exceptionally helpful.”

Now that spouses and families are confined together all day, we should be looking for new ways to define ‘home’. It isn’t someone’s property that is solely under their control, but a place for other members to feel real belonging and safety. There is no reason to not include ‘home’ as a variable in everyone’s work-life equation, because home is really part of every individual’s life.

We must all treat this time of social isolation as a period to change tiny beliefs and attitudes that can eventually contribute to the well-being and development of the society as a whole. In short, it is to become a cultural warrior for your own family and future generations.

*The opinions and ideas expressed in this article do not reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team.

Comments (0)