In the heart of Egypt, near Giza pyramids, an authentic place named “Ramatan” is located. The word may not sound familiar, however, it is an Arabic name for a place where Arab travelers used to rest at when changing residency. This place used to be home for the dean of Arabic literature, Taha Hussein. The famous writer used to live in this house with his French wife Suzanne Bresseau until his death in October 1973. Later, in 1992, it was decided by the Egyptian government to change this place to a public museum and a cultural hub.

Ramatan contains valuable heritage for Arabic literature. It’s also considered a cultural platform that hosts events to share how Egypt structured its culture in the 20th century.

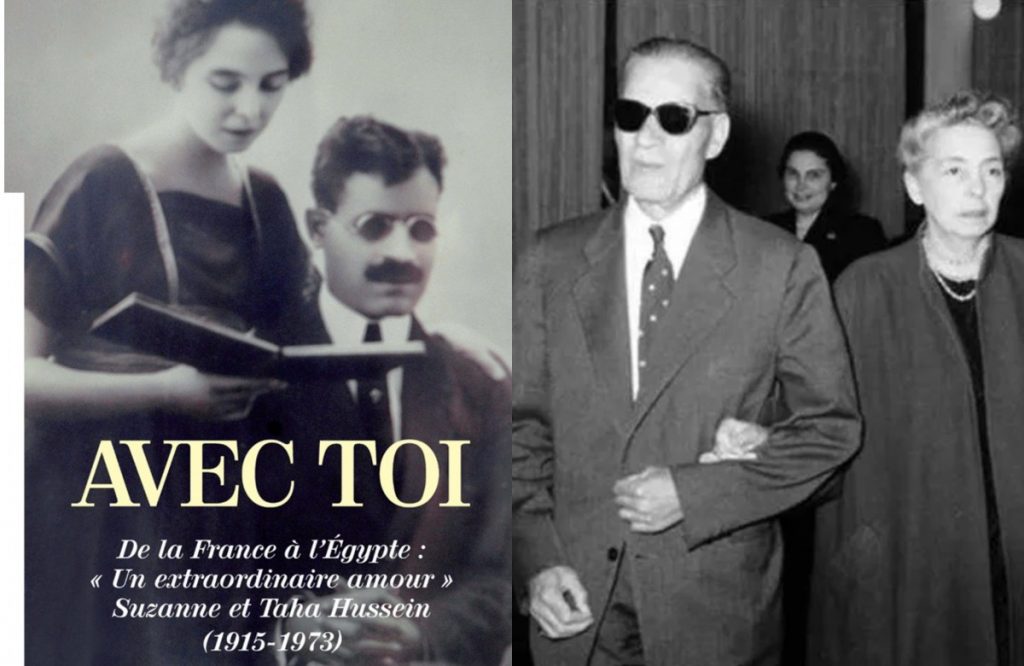

Hussein was a brilliant writer and so was his wife. One of Bresseau’s works that is constantly overlooked is a book she wrote about her life and love story with her husband, Hussein. The book was originally written in French with the tittle “Avec Toi” (With you), and it was later translated to Arabic.

Opposites attract?

The book narrates one of the most elegant love stories in the literary world. The elegancy here is cultivated from the contradiction found between Bresseau and Hussein in terms of religion, traits and cultural back ground. Hussein is Egyptian; Bresseau is French. He is Muslim, and she is Christian. He comes from a poor family, and she comes from an aristocratic one. Their love story was based on this diversity and the concept of acceptance.

In in the book, Bresseau tries to narrow down the gap one could make when this opposition is witnessed. Her family was ashamed of the situation at first, but Bresseau reflected on this saying “There is nothing to be ashamed of. There is nothing suspicious or sinful that may despise the human I want to share my life with.”

In fact, Bresseau was afraid she may lose her French nationality when she got married to Hussein, but her friends assured her that this will not happen. However, when she was getting on the borders of France on a trip with Hussein, she was shocked when the officer vigorously told her she was no longer French and she needed a travel permission. Hussein’s response to this situation was very calm “At this time, my deprived friend astonishingly, with his usual relaxation but throated voice said ‘we can get divorced’. This sentence was a beautiful attestation for his love.”

Exploring compromise

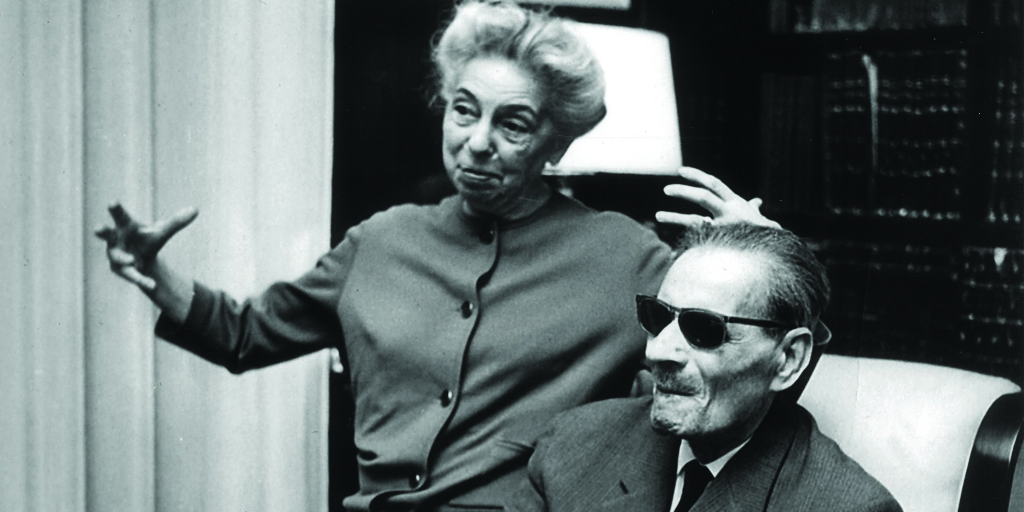

Bresseau and Hussein seem to maintain a respectful relationship where they understand that the different cultures from which they originate requires a mindset that accepts diversity. She was also told that the community Hussein comes from may practice religious intolerance. Before discovering that this is a stereotype she intuitively believed that the man she loved, as well as his family, will not practice any type of racism against her.

To prove this, she narrates a story of her first visit to Hussein’s family in a poor village. There, Hussein’s mother asks her what kind of wine she prefers. Drinking is against the norm of the village, but this incident gave Bresseau a sense of acceptance and acknowledgement by Hussein’s family.

Moreover, Hussein constantly opposes the idea and norm that women do not attend public events. In fact, he was always debating with the university board members on this saying that women presence generates a cultural atmosphere that gives a better shape for their events.

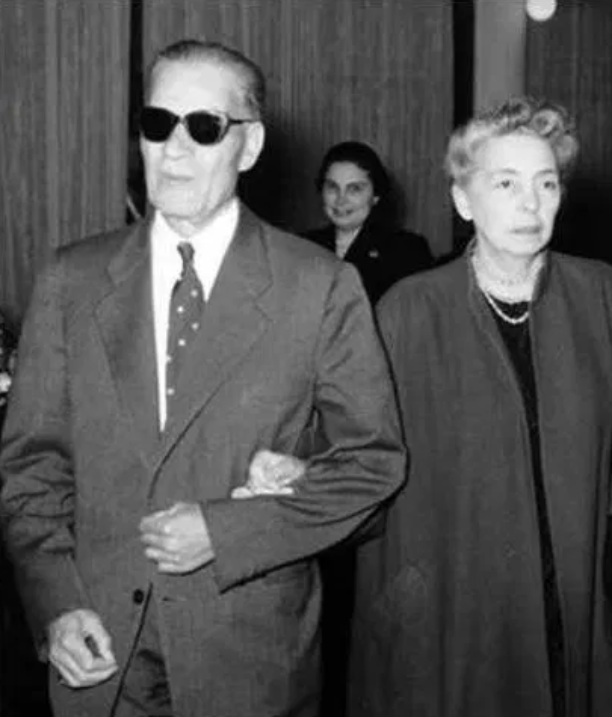

Contrarily to these members, Hussein proudly engages with Bresseau in public, insisting on her presence at conferences and occasions. Therefore, it was not strange for him to play an essential role in opening the doors for women to peruse a university degree. In December 1933, the university celebrated its first female class of graduation. It was a victory for the women union and Hussein as well.

Despite all these contrasts, their love story continued for 58 years; having two siblings, Mo’nes and Amina. During this period, they passed through tough circumstances but at the end they were side by side. Bresseau portrayed their last time together saying that she kissed his forehead. A forehead that time and pain didn’t change. It kept shining her life until the last moment.

Bresseau wrote this book in 1975, hoping to honor the mindful relationship with Hussein after his death in October 1973. The opening of the book can summarize it all: “We don’t live to be happy. When you first told me this in 1934, I was stunned, but I realized now what you mean. I know when one’s case is similar to Taha’s, then he doesn’t live to be happy, but rather do what’s asked from him. We were on the edge of desperation and I start thinking ‘we don’t live to be happy or to make people happy’. I was wrong. You donated me happiness. You did your best to be brave and hopeful. You believed that happiness does not exist on earth but this is a result of you being so humble, so you were not searching for it. I hope you are feeling it now.”

Comments (0)