Although Egypt boasts a long history and tradition of literature, from ancient Egypt until today, very few modern writers come to mind when perusing modern local literature. One prominent writer, still publishing engaging and slightly controversial material, however, is Alaa Al Aswany.

A dentist turned writer, the Egyptian author is most well-known for best-selling novels The Yacoubian Building and Chicago among other pieces of non-fiction and fiction works which have been translated into 37 languages. Indeed, famed novelist and revolutionary Al Aswany’s provocative work has earned him memorable features in the The Times and Foreign Policy magazines.

His work of fiction is deemed popular although his articles and work of non-fiction are considered niche. Indeed, following the 2011 revolution and political instability the following years, Al Aswany’s books were blacklisted. As a result, “The Dictatorship Syndrome”– which heavily questions the system of dictatorship and its prevalence worldwide – came to be; it captures the essence of his non-fiction work and is relevant to a non-Arab and Arab readership considering the global political climate today.

“What was the difference between a youth who has grown up in China or Egypt and a youth of the same educational level in Britain or America? How do traces of dictatorial attitudes find their way into the behavior of the everyday citizen?” muses Al Aswany in this book. Such general questions on the origins of dictatorship functioned as the sprouting seed of this ambitious work, which the 63-year-old’s took to analyzing through personal observations and more objective brain-pickings.

So sensitive was/is the subject that Al Aswany hid the brewing, half-finished material during his travel out of the country, Egypt, as to evade potential issues with authorities with whom he had tense a tense relationship with. “[…] I copied the half-finished book onto a USB drive and hid it between the toothpaste and shaving cream in my washbag as I left the country. Whenever I enter or exit Egypt, the authorities pull me to one side and make me wait as they go through my suitcase twice before letting me go. Had they found material for a book, they would have confiscated it and had it examined by a committee of officers and I would then have, most probably, been hauled off to court and seen levelled against me yet another charge of “slandering the institutions of state,”” he narrates.

Not unjustifiably so, the book explicitly criticizes, scrutinizes, and attempts to dissect political matters in Egypt. While one can clearly argue that Al Aswany uses his personal voice and opinions as a leitmotif against the current political structure, it would be more accurate to use the term ‘dissection’ to address this piece of work. A dentist by profession, the writer attempts to dissect and compose a ‘medical’ report of a political system which often times finds itself present in different countries – dictatorship, in all its manifestations.

Composition and style

The book is divided into nine chapters, spread over an average of 150 pages, where Al Aswany makes use of a personal narrative and moments of introspection when dwelling into national events. He alludes regularly to the rule of previous president Gamal Abdel Nasser and his military exploits. Indeed, he starts by framing the importance of propaganda, the depiction of the military and the effect of propaganda on Egypt’s population.

“We’ll be drinking our tea in Tel-Aviv by the sea,” Al Aswany recollects, on the confident cloth slogans meant to highlight Egypt’s faith in winning the war against Israel in 1967.

These personal observations and memories help emphasize that, after all, the understanding of dictatorship is a subjective one, based on experiences and the processing of knowledge in a subjective fashion.

The language Al Aswany adopts– much like in his works of fiction – is clear and the chapters are short enough as to not make the reading overbearing or distracting.

Shortcomings

Despite many of the book’s great observations and thought-provoking insight, there are parts that fall flat on reader eyes. In chapter one, Al Aswany attempts to compare British and Egyptian attitudes to holding on to a former leader; the difference, he concludes, is that the root of the issue lies in religious difference in that Muslims were more receptive to authoritarianism. However, this simplistic argument falls apart immediately when we recall that dictatorships have been in place in Argentina, Italy, Spain, Germany, Portugal, Chile, and many other non-Muslim countries.

Moreover, he simplistically reduces the attachment to a dictatorship system in Egypt as being plagued with ‘submission’ rather than analytically contextualize inherited attitudes and perspectives, as well as the inheritance of deep-rooted class issues, poverty and colonialism which fortify such behaviorism and political complacency.

The Dictatorship Syndrome often falls prey to oversimplified arguments which can be interpreted, sometimes, as reductionist fallacies. For example, when considering chapter 2 and the mention of ‘hypocrisy’, the author asserts “Every citizen understands that not everything that takes place can be spoken about, and that not everything that is spoken about is necessarily what is taking place.” This ‘hypocrisy’ is by no means unique to Egypt and can be noted in most countries, even those that are considered ‘democratic’ by today’s relative standards.

Moreover, there are certain phenomena one would question if truly associated with dictatorship as opposed to general political apathy brought on by a general need to generate income and maintain livelihood, such as here: “The good citizen creates their own safe microworld in total isolation from everything going on outside it, and they are completely uninterested in anything except earning enough to bring up their children. Their sense of belonging is restricted to their spouse and children. They will give greater priority to tracking down a drug to increase their sexual potency than to the drafting of a new constitution for their country, just as to secure an employment contract in the Gulf for their son is more important than securing free and fair elections.”

Sometimes, these oversimplified and matter-of-fact arguments can also seem quite banal, such as in chapter 7, he mentions that dictators play on the emotions of the audience. While this is true and has been proven through the study of political figures’ oratory skills and the reaction of masses to speeches, one would believe that the performance of ‘dictators’ relies on more than simply tuning to the emotionality of the public.

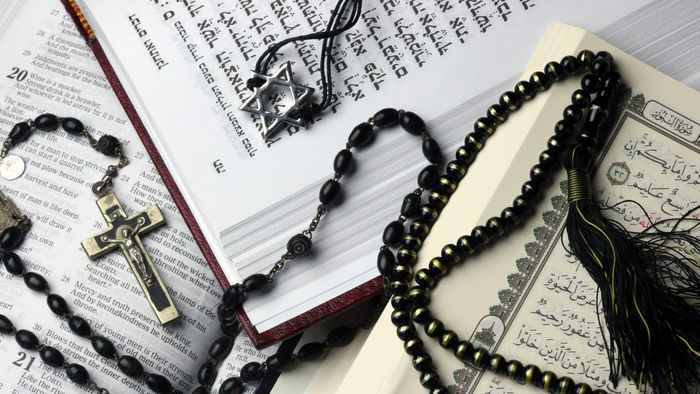

Moreover, this argument takes a hit when Al Aswany, as he fondly and recurrently does, brings about a comparison between religion and dictatorship: “Like religion, dictatorship plays a role in the control mechanisms used on the masses, numbing their intellects and manipulating their emotions in order to produce blind faith and total submission.” As Al Aswany explains, religion is often not chosen but is inherited through nurture and nature, however, one wonders how well this comparison falls through considering how vastly different these two systems are.

Great segments of analysis and definition

There are many remarkable points of analysis and descriptions in the book that give it its unique sheen. True to the original intent of the book, Al Aswany tries to dissect the different aspects that give life to dictatorship and the life of a dictator: conspiracies, fascist mindsets, importance of political propaganda, the stifling of intellectualism and opposite, the manipulation of media and so on.

It is particularly creative of Al Aswany to try to tackle the system as if the concept is a disease, with symptoms to be studied and mulled over. Chapters 3 and 4 are particularly outstanding in terms of ideas whether about the role of the dictator or that of the media. Chapter 4, in particular, focuses on conspiracy theories: not only does he tackle how modern leaders use conspiracies to keep people as ‘sheep’ but also how that is used to delay democracy, as well as the dehumanization of political opponents for the advancement of certain goals.

“When shooting an adversary, do not look into his eyes.” There is no clearer example of dehumanisation. If you think that the people you are killing are your enemies, it is much easier to shoot them dead. But if you looked into their eyes, you would see not an enemy but a human. You may see a young man, an ordinary person like yourself, and perhaps then you might imagine his mother’s grief if you killed him, or imagine him cuddling his children if he returned home. You would not then be able to open fire on him, because you would realize the enormity of the crime you would be committing,” reads Al Aswany.

Overall, he develops numerous great ideas that help study what has often repeated itself in time, and place, namely in Egypt considering its political climates through the last decades. The reader is invited to dwell on the concept of dictatorship while being presented with the opportunity to study its implementation in various countries in contemporary history.

Comments (2)

[…] renowned Egyptian writer Alaa Aswany, author of the Yacoubian Building (2002), paved the way for Egyptian modern political literature, […]

[…] renowned Egyptian writer Alaa Aswany, author of the Yacoubian Building (2002), paved the way for Egyptian modern political literature, […]