Growing up in an unwelcoming city for women with strict parents, I never developed a sense of ownership over Cairo’s streets despite having lived here my entire life. I was 18 when I took them on, alone, for the first time, bursting a bubble that had persevered for too long. One day, I was exploring the streets of Korba, looking for a place to get coffee before starting my day at my internship. I realize, today, the distinct aroma of espresso remains tethered to my addiction to the idea of freedom.

Since I was a child, influenced by Disney Channel ideals and fabricated brand name dreams, I craved the so-called independence of being abroad, particularly in the West. Daydreams of my future big American adventure were constant, slowly manifesting themselves into what I envisaged to be the “only way” to become who I really am, not knowing exactly what the self-realization would entail or with whom.

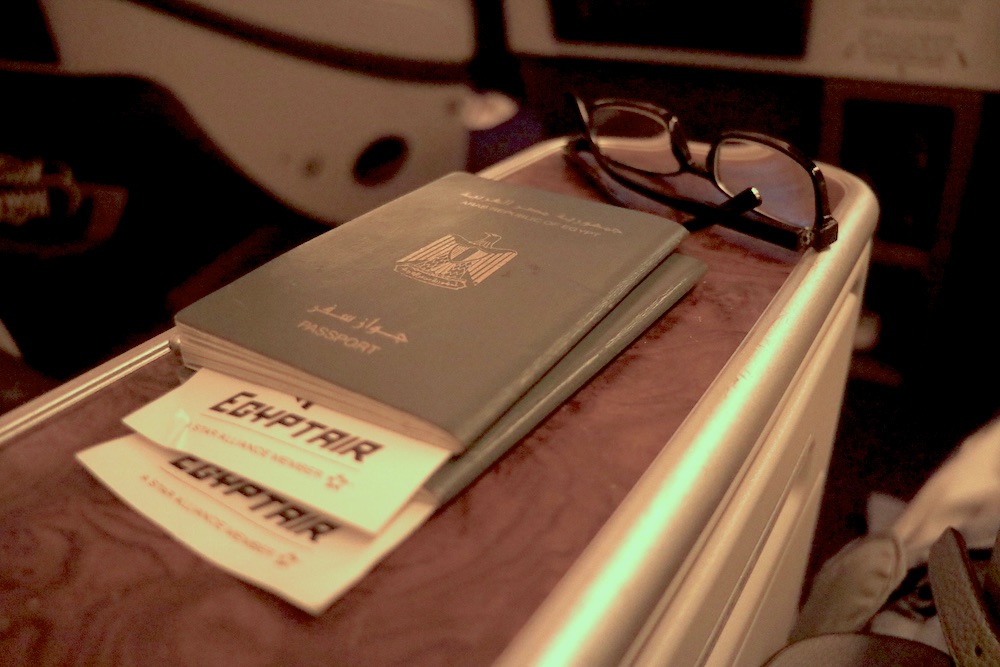

I had to think myself so far away, a 12-hour flight away, to feel that independence was realistic: New York became the platonic ideal. A year after my Korba internship, on a trip to the Big Apple, I wrote in my journal, “I swear I was born to live here. I haven’t felt as happy as I do when I’m here. I never want to leave.”

This New York trip in 2019, justified by a Model UN conference, was life-affirming and added to the already omnipresent resentment I had for my Cairo home, that I naively perceived as small, narrow, closed-minded, and lacking in opportunity. Cairo is many things, but I know now it surely is not small. If anything, Cairo is everything the world has to offer wrapped up in a dusty, crowded metropolis that quite literally never sleeps.

The contrast was stark: New York, the land where dreams are made, and Cairo, my mental repository for all that was wrong in the world. New York was El Meshmesh; a hypothetical place I’d get to chase my dreams in, someday. As such, the more I explored the foreign, the more I grew hateful of Cairo.

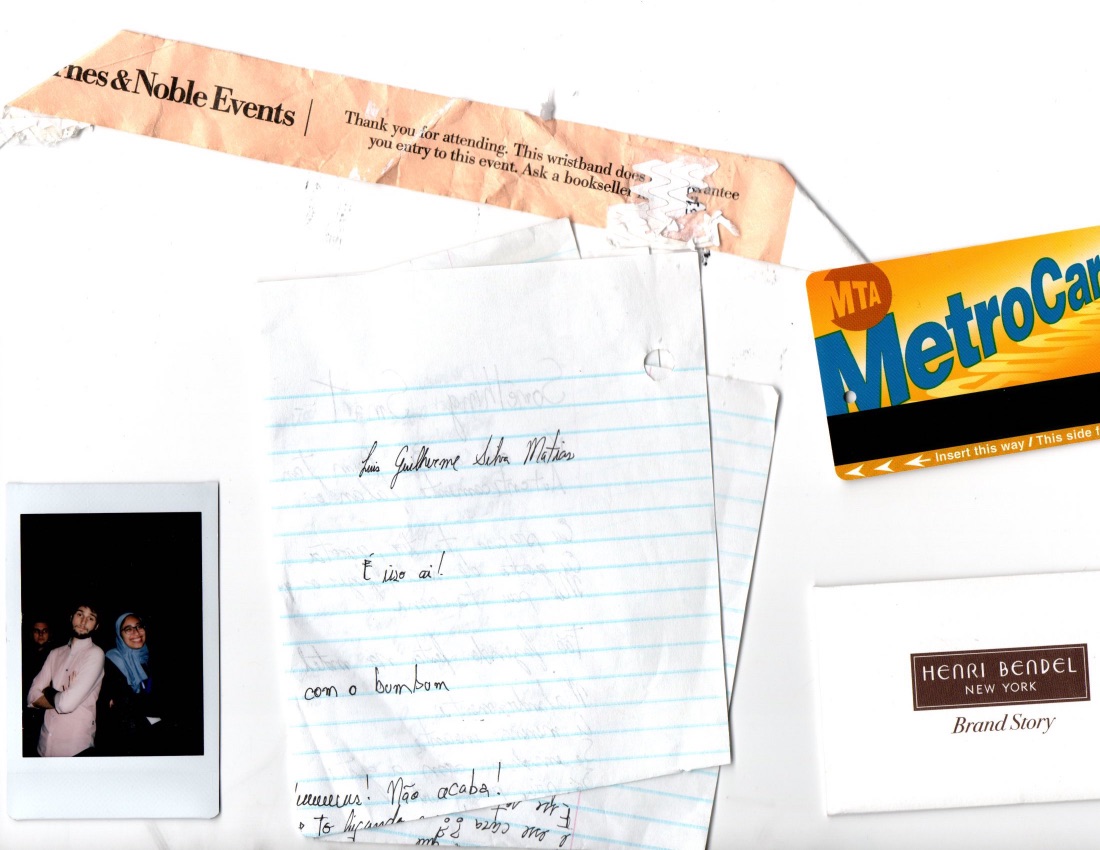

Upon my return in Cairo, I decided I was stuck, and resentment was flowing through my body. With resentment, comes limitation; the creation of a tiny world where opportunities don’t exist and all doors are closed. For years after that, I lived in that tiny bubble filled with overdue teenage angst in a small Cairo suburb I barely left. I spent my time in Cairo glamorizing every New York memory as fragile scenes of my cherished and short-lived independence, no matter how silly. There was the time I walked, alone, the Brooklyn Bridge when I got yelled at by a biker. There was the time I saw a broadway show by myself, loneliness overshadowed by the victory of solitude. It was in NYC that I experienced the simple highlights of being 19: sleeping in a hotel room by myself, catching the train to go vintage shopping, drinking bubble tea, or even opting to do absolutely nothing.

Coming back to Cairo, fascinated by the New York subway and yearning for the independence this mean of public transportation could offer, I was hesitantly inspired to try Cairo metro, which stops nowhere near me. It was already a privilege growing up not forced into the male-dominated world of Cairo’s public transportation, I acknowledge that. Yet, there is an underrated freedom to decent public transport that I don’t think many Cairenes care for.

I get one tiny step closer to understanding the city while using it. I get to Al-Ahram station, not far from my childhood home in Heliopolis, and I imagine a Cairo I get to experience on my own – not yet sure if I even want to. Kolleyet El Banat, Cairo Stadium, Cairo Fairgrounds, Bab El Shaaria, and finally Attaba station. I exit after getting lost more than once, and walk a long street to get to the restaurant I intend to meet my friend at.

I enjoyed the Cairo escapade, but it’s easier to escape your problems in a new, far away place than a location a few minutes away from home. Manhattan was still a more appealing island than Zamalek. The Nile was bleak next to foreign oceans. I deemed the Statue of Liberty more exciting than the Pyramids – it isn’t, I also realize now.

My map of Cairo was a square, with the four corners being wherever I lived, went to school or college, and hung out with friends. The thing about growing up in a big city is you never truly appreciate it until you intentionally decide to explore it as if you were a tourist.

I recently interviewed an Egyptian filmmaker who brought my attention the concept of “coming of age”, most heard in loglines of Western Films with first-time drunk teenagers, debut intimate experiences, or eighteen-year-olds living alone, and sometimes experimenting with drugs. As an Arab, Egyptian, Muslim woman, I enjoy these films but I never relate to them personally, while others may. They were more fantasy than reality, it was an “other” experience across the Atlantic, but almost always the only experience portrayed in film and series.

In 2017, I started college a mere 15 minutes from home and I start watching Grownish, a series about an American college student and her wild experiences. There are few TV series set in college and, by the time most of TV’s characters get to university, they’ve somehow already experienced everything in high school – unrealistically, to say the least. The show frequently made my college experience feel incompetent. I didn’t desire drinking or partying, but I also felt like something was missing. Am I not coming of age? Is living with my parents inhibiting my growth? These were all questions constantly swirling through my mind. I couldn’t help but be jealous of students in my Cairo-based university who were from Alexandria, or other cities, who had to move out alone to Cairo. They were getting the true college experience.

University was a turning point in more ways than one. My hijab, which I never thought of as more than a religious accessory in high school, became a signifier of me. Through cultural stereotypes, it told people things I didn’t hold true to myself. I took a few acting classes in college, a field with shockingly few hijabis, where I could feel the kid gloves I was being handled with in conversation. With nothing but respectful intentions, I was being handled like a tante (auntie) sticking out like a sore thumb in the middle of college kids.

Naively, I picture my coming of age to finally come in middle-of-nowhere Maryland, USA at a student conference later in 2019. During that trip, I experienced what Felukah calls a culture “buzz” rather than a culture shock, and satisfyingly, my own iteration of a coming of age. It hadn’t come in the form of a first alcoholic drink, or, God forbid, a sexual encounter with a white man, in a Ramy-esque fashion, but it did involve seeing myself through someone else’s eyes.

Every day of the conference, a group of college students, myself from Egypt and the rest from across North America, would gather in a hotel room to unwind. It involved drinking games, where I abstained from the drinking but was all in for the games. While opting for a non-alchoholic cranberry juice, I realized I was the only one abstaining, which made me see how people thought of me, unfiltered, without seeing me through a veil that I was still wearing. They weren’t intentionally doing anything different to include me, they were just unfamiliar with the cultural stereotypes even I held about myself, that I was supposed to be quiet, conversationally modest, a representation of an entire community, or limited in my choice of beliefs.

They talked to me in a way I hadn’t realized I’d never been talked to before: as a human with desires, wants, needs and interests beyond my choice of beliefs or clothing. They started conversations without prefacing with “sorry, we’re about to talk about something haram.”

The real culture buzz, I realized, was my own need to leave Egypt, where I was the norm, to leave my internalized stereotypes, and to feel normal.

Coming back to Cairo from that trip, I sluggishly walked through my AUC campus, under the impression I would never experience the level of understanding I experienced as a foreigner in the US.. I wished myself away to a random city in a random state that meant nothing to me. It became no longer about the place, but the people. And truly, it wasn’t the people but the expectations I had for my own coming of age.

Only half a year later would I meet those who took me outside my Cairo square. Cinema nights in Emad El-Din became night walks in Wust El Balad where the backdrop of rain and the occasional art gallery almost felt like New York. Laughs of loved ones echoed through the streets, this time in Arabic, and I didn’t feel like I had to be a foreigner anymore.

It was never really about New York, or the drinking or partying. I had stayed inside my Cairo square longer than I’d like to admit, and wherever the square is geographically, it’s still closed unless you open it yourself. I still yearn for a kind of independence only a far distance can provide, but it is no longer the only option.

My square is bigger now, but it’s still a square, filled with angst, privilege, and remnants of a closed upbringing. I struggle thinking about a time when it won’t be, my comfort zone stays and those the laughs are shared with are ever-changing. Whether it’s in Maadi, or Dokki, or Heliopolis, I’m still getting a tiny portion of the Cairo experience.

That’s the thing about Cairo, it’s one city out of over 200 in Egypt and it holds millions of stories. If in two decades, I haven’t scratched the surface of Cairo, how dare I even want to search somewhere else, let alone a different country miles away? Getting on a plane is a fast-track to independence and coming of age. Alternatively, Cairo provides a beautiful, different, constant, life-long, messy arrival.

Comments (3)

[…] From Cairo with Love: My Fabricated Coming of Age […]

[…] Source link […]