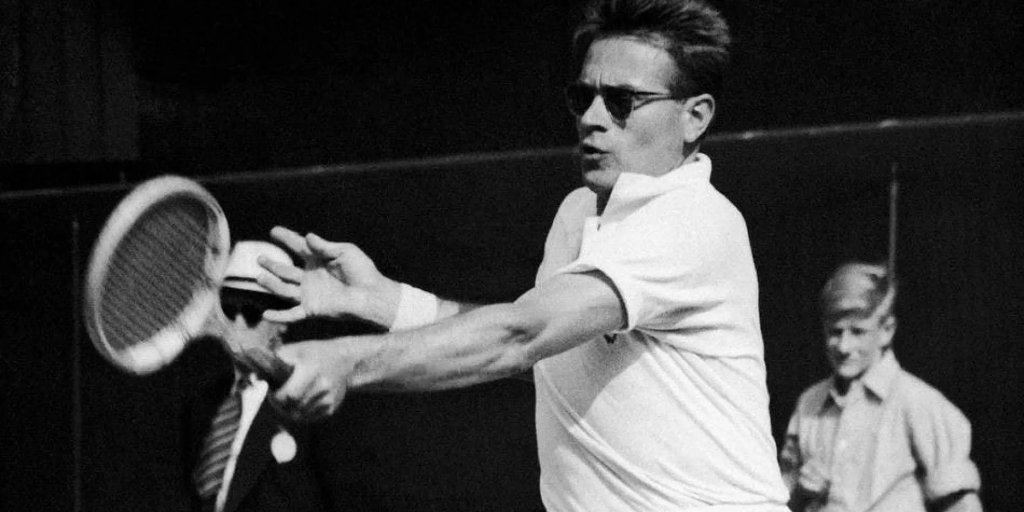

It was a searing day in June 1954, when a cool and collected man in dark sunglasses triumphed in tennis. The London crowd could not stop celebrating the new champion of Wimbledon. To the Western world, he was a beacon of democratic liberalism; to the East, he was an evil Communist exile. On paper, he was an Egyptian national – to this day, the only Egyptian to ever champion Wimbledon.

His name was Jaroslav Drobný. He was the furthest thing from being Egyptian, yet only found glory through his Egyptian naturalization.

Born as a Czechoslovakian in Prague in 1921, Drobný was a child of many athletic talents. Besides making his Wimbledon debut at the tender age of 16 in 1938, he was also a cornerstone of Czechoslovakia’s national ice hockey team. Despite his smooth talents, his youth was not as smooth.

The German invasion of Czechoslovakia introduced the sport prodigy to the horrors of war. Drobný spent World War Two working at a factory in Prague, witnessing torture and segregation in his community.

By the end of the war in 1945, Drobný saw a return to both tennis and ice hockey. He won gold and silver medals in the World Championships and Olympics for ice hockey respectively but did not achieve the same success in tennis during this time.

Political turmoil continued to distract Drobný, this time through the Communist coup d’etat of Czechoslovakia in 1948. Prior to the seismic Soviet shift of his motherland, Drobný had already visited Moscow in 1947, seeing “enough to make [him] realize that [he] could never live under such a regime.”

“Quite simply, I hated being told by some Communist where and when to play because it suited their political aims and ambitions. At the time the Communists realized far better than Western democracies the tremendous propaganda level of international sport,” he wrote in his autobiography, A Champion in Exile (1955).

As the Communists in Prague began to serve Soviet dialectics onto tennis courts, Drobný refused to continue. In 1949, Drobný was determined to defect, doing so during the Swiss Open in July.

“All I had was a couple of shirts, the proverbial toothbrush, and 50 USD (925 EGP),” he wrote.

Drobný was required to represent a country in order to participate in international tournaments. He, first, defected to Switzerland, only to be met with rejection. Then, America: rejected. Britain and Australia were his last shots – and once more, Drobný was rejected.

In a state of statelessness, Drobný desperately needed a nationality to resume his tennis career. Then, Egypt came to the rescue in 1950, offering the citizenship to which Drobný happily accepted.

The Czechovoslakian exile was now reborn as an Egyptian. Culturally, he was as much an alien before being Egyptian as he was after his naturalization. Now a veteran of tennis at the age of 29, it was evident that Egypt would never be Drobný’s home. Though for the meantime, Egypt was his rescue; his ticket to one last shot at glory in tennis.

During his time in Cairo, the former Czechkoslovakian would train at the Gezira Sporting Club to sharpen his skills, participating each year in the Egyptian Open tournament – winning consecutively from 1950 to 1953.

Image Credit: Alamy

It was while representing Egypt that Drobný finally began to become the best in the world, winning Singles tournaments for the first time in his career after decades of losing finals and semi-finals. A back-to-back French Open victory in 1951 and 1952 was his first taste of glory, but Drobný still coveted the illustrious Wimbledon trophy – losing the finals once in 1949 and in 1952.

In 1954, 33-years-old and at the swansong of his tennis career, Drobný finally achieved Wimbledon triumph. Known as ‘Old Drob’ by that point, the Egyptian Czechoslovakian carried an air of cool confidence throughout the tournament.

“[The Singles] is the most important title at Wimbledon and if I did get beaten early on then I could have a pleasant holiday watching the other players,” Drobný remarked during the start of the tournament.

He never got the chance to enjoy an early-elimination holiday like he joked, making it all the way to the Wimbledon Singles final for a third time in his career. This time, however, he won it.

While donning dark sunglasses, Drobný defeated the Australian, Ken Rosewall, to finally lift the Wimbledon trophy. And he won it as an Egyptian. The only African Wimbledon champion to this day.

Drobný’s success story with Egypt would come to an end after his naturalization to Britain in 1959. A year later, at the ripe old age of 39, the man of many flags ended his tennis career at one last Wimbledon tournament.

Drobný was always destined for greatness in tennis. It just so happened that he achieved all his glory as an Egyptian, as a representative of the country that offered him the chance to be a champion.

Comment (1)

[…] […] مساحراتي: تقاليد رمضانية متجذرة وشعبية […]© 2019 Egyptian Streets. All Rights Reserved.Subscribe to the fastest growing newsletter in Egypt. […]