Tender in voice and powerful in impact is Mohamed Mounir; when he enters the stage with his bright smile, hundreds of thousands line up – because Mounir is an Egyptian sensation. Calling for peace and justice, Mounir’s Nubian musical style and socially-conscious lyrics earned him the title ‘king’ for nearly four decades in Egypt. A legend, Mounir has been described as‘ ‘the best Arab singer of the 20th century.’

Although largely dominated by the Arab-trap scene in recent years, Egypt was not always a hub of rap and electronica. Mounir pioneered the introduction of Nubian artists and influence in Egypt’s music scene – becoming a nation-wide familiar voice to all.

Born in 1954 to a Nubian family in Aswan, Mounir spent most of his childhood in Masnshyat al-Nubia, a village later flooded by the construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1970. This forced his family to move to urban Cairo.

A star is born

Mounir had a heart for the arts; he studied at the Faculty of Applied Arts at Helwan University, and during this time, he began his journey as an aspiring pop singer. He was recognized for his talent and taken under the wings of poet Abdel Rahim Mansour and Nubian folk musician Ahmad Mounib. Even during his military service in 1974, he continued growing his professional musical career by singing in various concerts. After completing his service, Mounir released his debut album Alemony Eneeki (‘Your Eyes Taught Me’) in 1977, and from there, a star was born.

His musical sensibility and distinctive style helped him stand out as a genius who incorporated various genres into his music, including classical Arabic Music, Nubian, and also jazz.

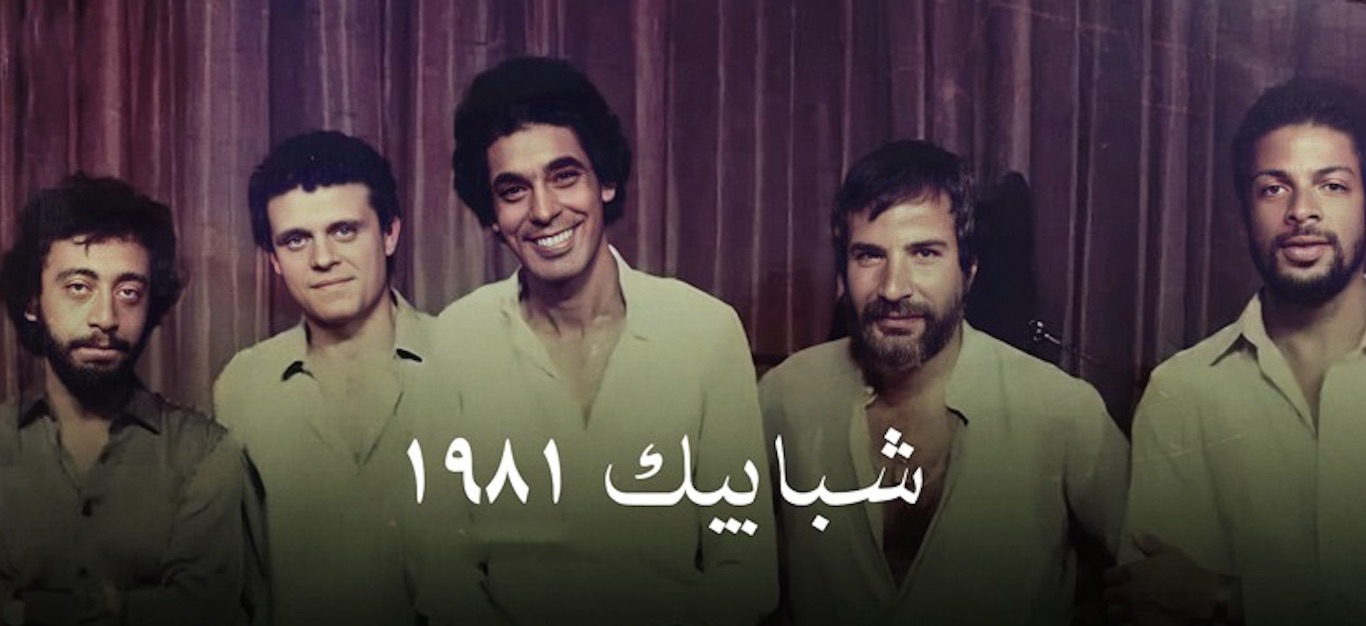

During the 1980s, Mounir started collaborating with Egyptian jazz legend Yehia Khalil on four albums, Shababeek (‘Windows’) in 1981, which was listed as one of the best Arabic-African music albums, Etkalemy (‘Speak’) in 1983, Baree’a (‘Innocent’) in 1986, and West El-Dayra (‘Middle of the Circle’) in 1987.

At that point, it was only natural for him to earn his famous nickname the ‘king’ of music, in reference to his album and play El Malek Howa El Malek (‘The King is the King’) in 1990.

Aside from his outstanding singing career, Mounir also explored acting, appearing in 12 movies, four television shows, and three plays. His movie career debuted with Youssef Chahine’s Hadouta Masreya (‘An Egyptian Story’) in 1982, a film he also sang the soundtrack for. Mounir also appeared in other movies such as Al Yom Al-Sades (‘The Sixth Day’) in 1986, Al Maseer (‘Fate’) in 1997, Mafeesh Gher Keda (‘Nothing But This’) in 2006, among others.

Though Mounir appeared in many television shows, ‘Bakkar’ (1998) remains etched in the hearts of all Egyptians. In 1998, Mounir sang the official theme song to one of Egypt’s most famous cartoons ‘Bakkar’, a series that followed the adventures of the young Nubian Bakkar.

Mounir’s music carries passionate social and political commentaries. In the 1990s, his music grew to reflect the cultural, societal, and political aspects surrounding him. In 1986, his song Al Qods (‘Jerusalem’) became an emotional tribute to Palestine.

He also became the first voice of the 25 January that echoed with his song Ezay (‘How’, 2011). In Ezzay, Mounir is believed to have compared Egypt to a negligent lover in the song, showing his love and appreciation for his country. His song Hadouta Masreya (Egyptian Story) also had a great impact during the 2011 revolution.

His album Ard El Salam (‘Land of Peace’) in 2002, conveyed his agony after the 11 September, 2001 fall of the Twin Towers. It won him recognition in the Western world as a voice that soars for reason and religious tolerance.

He released his last album Watan (‘Homeland’) in December 2018, and recently performed his first concert in 12 years on 15 July at Alexandria. With a career spanning decades, Mounir is a legend whose music speaks to generations.

Comments (4)

[…] الثمانينيات أنتج سلامة لنجوم مصريين مثل عمرو دياب ، محمد منيروعلي الحجار وانوشكا. كما حصل على جوائز عن الموسيقى […]

[…] the 1980s, Salama produced for Egyptian megastars, such as Amr Diab, Mohamed Mounir, Aly El Haggar, and Anoushka; he also won awards for his soundtracks for movies, including Gannat […]