Downtown Cairo’s Zawya Arthouse Cinema is currently hosting its Khairy Beshara Retrospective program, celebrating the Egyptian auteur’s work through a series of screenings and Q&A sessions.

I have been a faithful attendee since the program started on 5 January. Having never seen Beshara’s films in cinemas, I looked forward to watching stories I knew only from television unfold on a large screen. I expected to feel bittersweet nostalgia, but instead, was met with an uncanny sense of recognition.

From grueling neorealist dramas to vibrant musicals, decades on, these films still feel like acute reflections of our socio-economic reality.

Champion of the underdog

Khairy Beshara counts among the pioneers of Egyptian neo-realism, alongside Mohamed Khan, Atef al-Tayeb, and Daoud Abdel-Sayed. The 1980s movement aimed to be acutely faithful to reality, through naturalistic acting, on-site filming, and a focus on the lives of ordinary people.

Owing to their documentary quality, neorealist films serve as deeply accurate portraits of their time — a record of sociopolitical tides, but also of people, their habits, and the ever-changing urban landscape — inviting and facilitating comparison with the present day.

Yom Mor w Yom Helw (Bitter day, Sweet Day, 1988) is often cited as Beshara’s neorealist masterpiece, owing to its gritty depiction of life in Shubra’s impoverished Al-Assal area. Inspired by a real-life incident where one of the director’s neighbors died by self-immolation, the film offers an unflinching portrait of the intersection of poverty, patriarchy, and the ills of an overcrowded capital.

Though the area underwent renovations in 2016, poverty continues to plague its inhabitants, bringing continued relevance to the film.

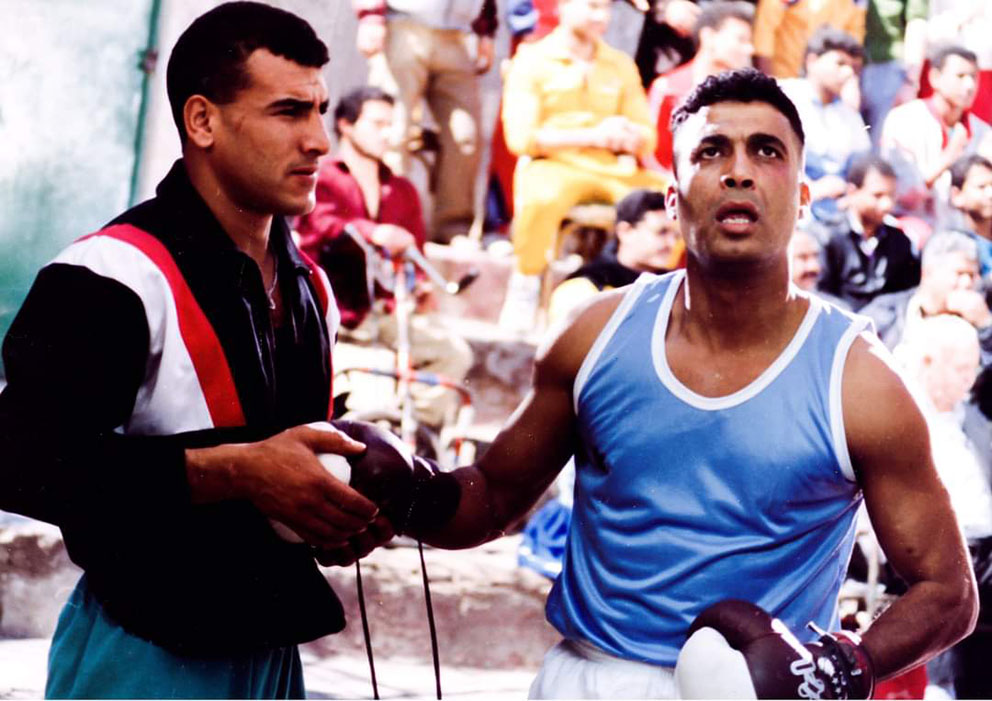

Where the parallels resonated most with me, however, was in his lesser-known second feature, Al Awama Raqam 70 (Houseboat Number 70, 1980). The film follows documentary filmmaker Ahmed (Ahmed Zaki) and his journalist fiancée, Wedad (Tayseir Fahmi), as they investigate rampant corruption in a cotton factory.

The Cairene landscape recorded in the film is a distant cousin of the city we know today. In its opening moments, the camera pans across the western bank of the Nile, and rests upon the titular houseboat, home to our protagonist. The houseboats, paragons of Cairo’s heritage and once home to some of its most memorable film sets, now feel like relics of a different era, six months after their demolition.

Another scene shows the protagonists at the Giza Zoo, engaged in a heated argument which sees them walk past gazelles, lions, and other roaring felines whose cries echo the two characters’ own ruckus.

The Giza Zoo, the oldest in Africa and the MENA, has closed its doors for the first time since it opened in 1891, and is undergoing renovations. Prior to its temporary closure, the establishment faced accusations of cruelty, and lost many of its inhabitants to neglect, mistreatment, and even depression — a far cry from the green wonderland portrayed in Houseboat Number 70.

Beyond the surface, however, much remains unchanged.

In one scene, Ahmed asks the factory’s owner to comment on the drop in Egypt’s cotton production, already in decline in the 1980s. In 2022, Egypt produced 420,000 bales of cotton, up from 280,000 in 2021: a substantial year-on-year increase, but still less than half of the 970,000 bales produced in 2007.

During one Q&A session held as part of the retrospective program, Beshara recounted that in their time, neorealists were criticized for portraying Egypt in a negative light, a fact to which the film makes direct reference. Similar accusations are still pointed at filmmakers today. One recent high-profile example is the 2021 film Reesh (Feathers), directed by Omar El Zoheiry, who moderated the aforementioned Q&A.

Fantasia with the grainy texture of truth

The 1990s marked a new phase of Beshara’s career, beginning with Kaboria (Crabs, 1990) in which the auteur drastically stepped away from neorealism in favor of surrealist comedy and musicals, infused with what the filmmaker called “fantasia.”

During another Q&A, Beshara recounted that Kaboria was released in a private screening to very negative reception. Despite critics’ unfavorable response, heaps of young people still flocked to see it in cinemas, memorized its titular song, and adopted its hero, Ahmed Zaki’s, hairstyle.

This loving fanbase cemented the film’s status as a cult classic — and Beshara’s as an industry rebel, favoring an audience of young adults over critics, and artistic integrity over laurels.

This stylistic shift extended to the director’s subject matters. While his previous films were mostly grounded in the world of Egypt’s working class, these later works shifted their focus to inter-class conflict, and young people’s dreams of rebellion and escape.

Most striking to me, in this regard and every other, was Ice Cream in Gleam (1992).

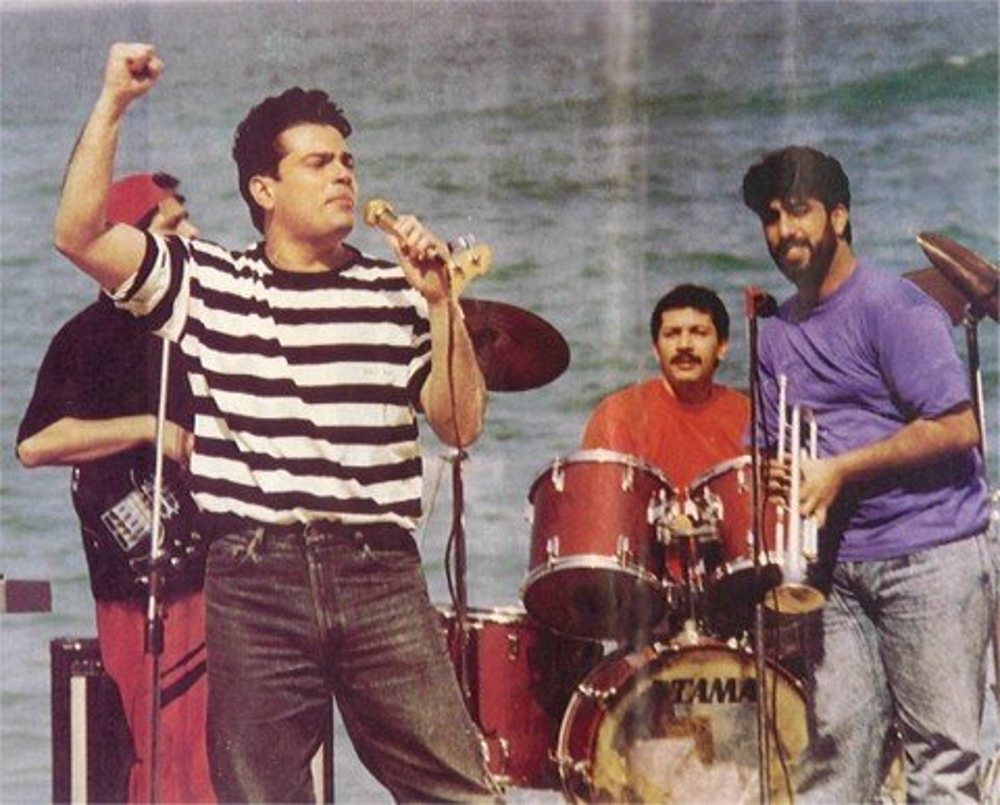

The 1992 feature follows Seif (an endearingly naive Amr Diab), who works as a delivery man and dreams of making it big as a singer. He lives in a garage in Maadi and spends evenings jamming with equally downtrodden friends. In their nightly gatherings, the young men argue, share laughs, and contemplate the bittersweet release of emigration.

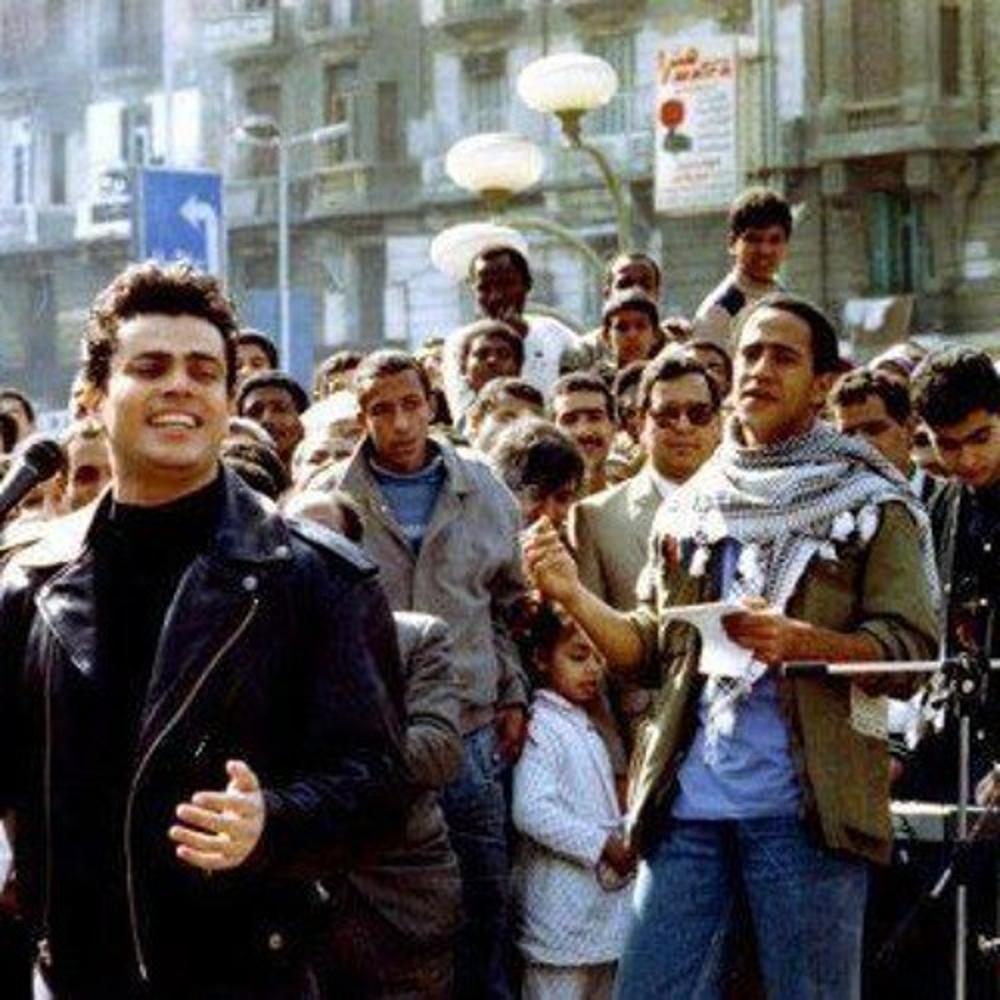

When a street altercation lands him in jail, Seif befriends Marxist poet Noor (Ashraf Abdel Baky) and mad genius composer Ziryab (Ali Hassanein). The trio form a street musicians’ group, splitting their time between Cairo’s sidewalks, restaurants, and jail cells.

Seif parts ways with his unfaithful fiancee, Badreya (Simone), and rivals Nour for the affection of the beautiful Ayah (Gihane Fadel). When Seif finally lands his first official gig, the newly formed couple kiss passionately on the beach in Alexandria, as the titular song calls in the closing credits.

On the surface, the cult musical is a colorful ode to youth. Beneath its whimsical exterior, however, the film is a vocal call to rebel against the commercialization of art, cultural norms, and inequality.

For one thing, Ice Cream in Gleam cemented Beshara’s position as a voice of the youth, rather than the gatekeeping intelligentsia. For another, it marked a rejection of the saccharine tropes of commercial cinema. While a lesser film would have had Nour and Badreya suddenly lock eyes – and lips – in its final scene, Beshara leaves them to their tears, reminding us that there are no monolithic happy endings.

As film director Ayten Amin noted during the Q&A session, which she moderated, “[Ice Cream in Gleam] is the most 90s film ever.”

Indeed, Seif makes deliveries for a video club owned by sleazy Ziko (Hussein Al Imam). Rhythming his escapades are impromptu choruses of rollerbladers and parties of girls savoring soft-serve ice cream in December. Colorful, kitschy, and highly stylized, much of the film looks more like a retro advert or music video than a work of auteur cinema.

Yet, the early 1990s were not all pop and sunshine: the period also marked the fall of the Soviet Union. In its wake, America’s Cold War victory promised to usher in an era of global freedom and abundance.

Liberalization is a prominent theme in the film, embodied in a fast-changing capital where the tides of change have brought a colorful sea of fast food chains. It takes human form in Ziko; in the hostile crowd at a private party where Seif is unwelcome; and in Badreya’s wealthy lover, Adham (Izzat Abo Ouf).

Through her entanglement with Adham, Badreya comes to be more than just a heartbreaker; she becomes the symbol of a status quo where love takes a backseat to material wealth. The salesgirl is candid about the reason for her infidelity: Seif is poor. She loves him, but not enough to endure a miserable life together. The song overlaying their breakup, sung by Seif, is literally titled Hatmarad ‘Ala El Wad’ el Hali (I Will Rebel Against the Status Quo).

This is not to say that Badreya is the film’s antagonist. Its real villain is perhaps not a character, but the structures of inequality within which the story unfolds, ones deeply familiar to contemporary audiences.

One scene, where the musicians give a politically-charged street performance, offers a sharp, grainy look at the faces of Cairene traffic. Mechanics in oil-stained overalls; a food vendor pushing his cart home; mothers carrying children on one shoulder and plastic bags in weary hands — a strong departure from the glossy feel of previous scenes.

Through these passersby, we are swiftly reminded of Beshara’s documentary origins. Save for a changing backdrop, they could have been captured today.

On Zawya’s screen, Beshara’s characters navigated the dizzying landscape of a crowded capital, strove for artistic freedom, and fought for meaning in a fast-changing world. And here we were watching them, thirty years on, still harboring many of the same hopes and dreams.

The Khairy Beshara Retrospective program is ongoing until 31 January.

The opinions and ideas expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comments (3)

[…] Why Khairy Beshara’s Cult Classics Are More Relevant Now Than Ever […]

[…] window.speakol_pid = 29 (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Why Khairy Beshara’s Cult Classics Are More Relevant Now Than Ever […]