Content Warning: This article includes images of wrapped mummified human remains and discusses body parts. Links may contain images of human remains. Please take care when reading and viewing this content.

In recent weeks, international media has reacted to the increasing attempt being made by museums to re-position ‘mummies’, not as spectacles on exhibition, but as real ancient people. One significant move in this re-positioning is abandoning the colloquial term ‘mummy’ in favour of a more humanising description, such as ‘mummified individual’ or ‘mummified human remains’.

However, it is not just terminology that is under increasing scrutiny – but the displays themselves. In turn, this has led some museums, including the Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney, to ask – is there such a thing as the ethical display of human remains, particularly regarding the often-sensationalised mummified people of ancient Egypt? And, if so, how can it be achieved?

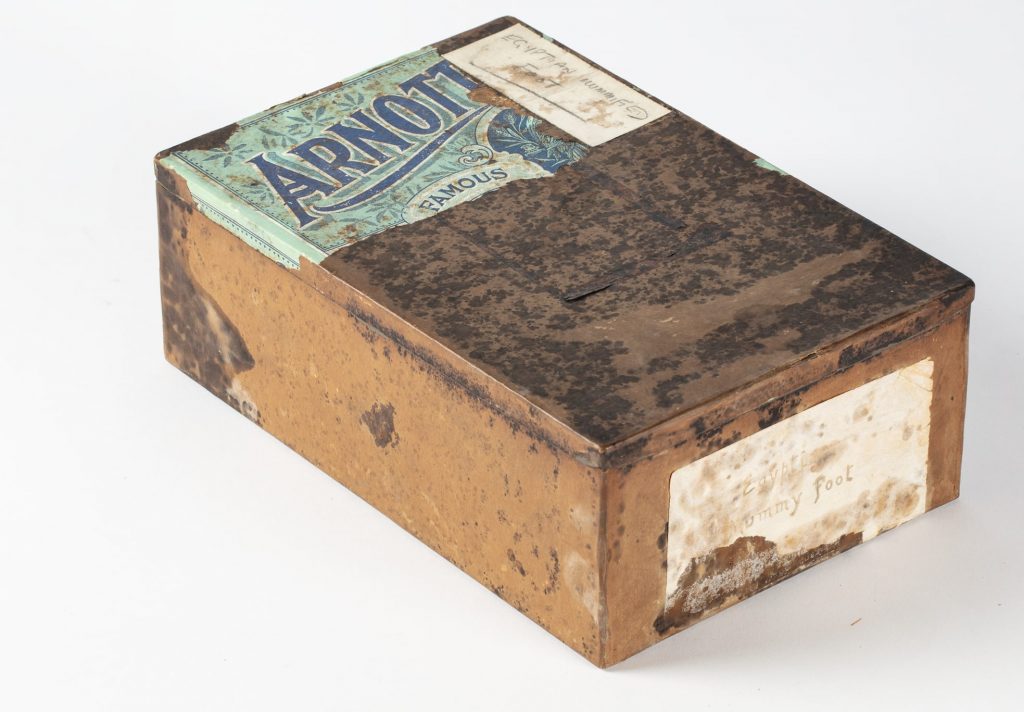

The Chau Chak Wing Museum currently displays mummified human remains in its Egyptian galleries. Some are wrapped and include CT (Computed Tomography) visualisations of the skeletal and packing materials; others are individual parts of bodies, partially-wrapped or completely unwrapped, with exposed bone and sinew.

How the Museum acquired these remains was addressed in our previous article, and a recent report on Egyptian collections, titled Egypt in Australia, investigates the distribution of Egyptian ancestral remains in Australia, including the Nicholson Collection.

Among the Egyptian displays are the remains of children as well as adults. The Nicholson Collection also displays and cares for ancient human remains, primarily skeletal material, from other cultures, including Jericho (West Bank), multiple sites in Cyprus, and of the 14th century French nobleman John the Fearless (1371-1419) and his wife Margaret of Bavaria (1363-1419).

As noted in a former article in this series, the museum includes a cultural safety warning sign for visitors at the entrance to the Egyptian Galleries and the display of the ‘Jericho Skull’. However, anecdotal evidence suggests this is frequently missed by visitors entering the space, thus raising questions about what cultural safety processes are in place and who do these serve?

Is there such a thing as the ethical display of human remains in museum contexts – especially when that museum is far removed from the country of origin of the individuals being displayed?

This question was put forward to the ongoing Australian-Egyptian working group, which is currently addressing the display of Egyptian cultural heritage, at the University of Sydney. While the museum curators acknowledge that this group does not represent the whole community, and no community is a monolith of opinion, individual voices are important in the first steps towards integrating more meaningful displays of cultural heritage for diaspora communities, particularly since the display of ancient Egyptian people in museums has long resided with museum professionals, not communities of descent.

A few members of the working group shared their insights.

Buried home: honouring the deceased’s wishes

“Asking senior people in Egypt, especially those who live in a town different from their original town, “What is your wish?” the answer is always the same, after wishing their families a happy life, they will say, “I want to be buried in my town, in my land.” The young generation laugh and ask “What difference does it make, where you are buried, you wouldn’t know nor feel a thing!” The answer again is always the same “Who said so?”. Of course, I will feel at home; I don’t want to be buried as a stranger in a foreign land,” shares Shahy Radwan, a masters student of Archaeology and Heritage Management, Flinders University, Capacity Development Coach, and a community advocate.

“This says it all. When these people whose bodies were displayed in museums were alive, they built their tombs to be their eternal homes, not to be dragged out, forced to travel, and be displayed for people to watch their bodies. This will make sense if we change the word (‘mummies’) to the word (‘bodies’) or (‘people’). The bodies of these people are being displayed here against their wishes, ” she adds.

Carefully curating display: making specific arrangements

“During my first visit to the Royal Mummies Room at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo – before they were transferred to The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization – I felt that I was part of these mummified kings and queens’ lives. I started imagining every story of each one that we learned at school and university. I imagined King Seqenenre Taa II (17th Dynasty) and his courage to face the Hyksos and how he was killed during the war from the injuries on his mummified body. I was very happy that the ancient Egyptians could survive their bodies to tell us the story,” narrates Arzak Mohamed, who is acquiring her PhD at the School of Natural Sciences at Macquarie University and an assistant lecturer at the Faculty of Archaeology, Fayoum University.

“I participated in the Australian-Egyptian working group, and I saw the display of remains of ancient Egyptian people. I am still proud of my ancestors and have no issue with displaying these remains at the Chau Chak Wing Museum; I am pleased to see the display of the CT results. The study of ancient mummies can help us identify the history of some diseases and genetics. But, I did not have the same feeling when I saw an infant’s legs on display in the “Antiquarianism” section of the Mummy Room, which was naturally mummified at an unknown date. When I saw these, I was not happy, and all of the focus group members did not like the display, probably because [the body] parts did not seem to tell any story or have a purpose and it felt like the person has just died now,” she further elaborates.

“I think museums should continue to display the ancient Egyptian mummies with full bodies and avoid display parts. Furthermore, mummified bodies have to be in a special room and the access to this room needs to be by request, and never displayed with other artifacts.”

Steering clear of objectification: giving back the deceased their humanity

“The presence of human remains in museums is always a contentious matter. However, we must work together to try to resolve the prickly issues that arise on such a controversial matter. Human remains in museums command the utmost reverence and respect. Mummified ancient Egyptians take on an added dimension as they are an extension of my culture, my lineage and my ancestors. Seeing them evokes the same emotional response as visiting my grandparents’ or parents’ grave,” shares Inas Ramzay, a member of the Australian-Egyptian community with a background in Education and community work.

“As a migrant, my limited connection to my heritage and my people is often experienced in a museum setting. It is crucial that the display of such material should move away from the display of an object to the display of a person with reverence and respect. Dismembered human remains disturbs me and upsets me to the core. It is a painful reminder of the vulgarity, greed and theft which marks their often violent removal from, and desecration of, their resting place,” says Ramzay.

“The distance of time and poor knowledge of their identity must not desensitize us from reality. The reality being these are the human remains of individuals that once lived and were engaged in living, as you and I writing and reading this article. The brief for curators of human remains in general, and Egyptian mummified remains, in particular, should operate under the umbrella of reverence unlocking the pathway of opportunity for knowledge, research, inspiration and wonder of the grandness of individuals of a bygone time and continuous uninterrupted civilization. Egyptian mummified remains are a significant part of the heritage of humanity. Connections should be highlighted in the display.”

An Ongoing survey

Between July-December 2022, the Chau Chak Wing Museum collected feedback from more than 200 visitors about their opinion of the museum’s current displays of human remains. It also continues to gather feedback from an ongoing survey of the local Egyptian-Australian community. Together, this will contribute to a wide-reaching community-driven, and data supported, re-evaluation of the display and ongoing care of human remains at the museum.

This article is part of an ongoing conversation series published on Egyptian Streets co-written by community participants from Australia’s Egyptian diaspora and the curatorial team at the Chau Chak Wing Museum.

Comment (1)

[…] Source link […]