Last April, the Egyptian series Taht El Wesaya (‘Under Guardianship’) made headlines amidst the year’s heated Ramadan television race. Co-written by Khaled and Sherine Diab and directed by Mohamed Shaker Khodeir, the show stars Mona Zaki in the role of Hanan, a widow fighting to provide for her children after her husband’s sudden death.

When her in-laws try to seize her late husband’s fishing boat – her only source of income – and take her children out of school, Hanan illegally retrieves the ship and flees to Damietta with her son and daughter, where they begin a precarious new life.

The series reaped praise for its raw portrait of single motherhood in a patriarchal society, exceptional cinematography — and for its role in initiating talks of reform to Egypt’s guardianship law, which dictates that a late father’s inheritance and legal guardianship of his children go to their paternal grandfather.

The social impact of Taht El Wesaya is not a standalone incident, but rather, reflects the role that Egyptian television series, known as mosalsalat, have historically played in shaping public opinion and pushing forward developmental objectives.

The rise and fall of developmentalism in Egyptian television

Broadcast television was first introduced to Egypt in 1960, shortly following the overthrow of the monarchy and the country’s transition to a republic. Initially, it comprised only three state-owned channels catering to slightly different audiences.

In her 2005 book, ‘Dramas of Nationhood: The Politics of Television in Egypt,’ anthropologist Lila Abu Lughod explains that Gamal Abdel-Nasser’s government viewed television as a tool of education and development.

As such, substantial investments were made towards mass media production and subsidies to bring this new medium to rural areas. It was important that as many Egyptians as possible gain access to television, as early programs played a key role in nation-building.

The first Egyptian television series, Harib Min Al Ayyam (‘Running Away From Time’), began broadcasting on 23 July 1962, on the anniversary of the revolution that overthrew the monarchy. Based on a story written by Tharwat Abaza, the show starred Abdallah Gheith in the role of a poor drummer living in a rural village, where he is mistreated by fellow villagers.

Its themes of poverty, class disparity, and criminality served to remind viewers of the social ills that plagued the country under the monarchy, and how socialist policies promised to make them a thing of the past.

Another marker of the era’s politics was state feminism — the governments’ adoption of gender-focused policies in line with its developmental and political objectives. Its main vehicle was melodrama: a genre with a primarily female audience, used to present aspirational models of womanhood and citizenship.

By the 1980s, Ramadan serials had become a staple of Egyptian television. Though liberalization in the Sadat era had invigorated the private sector, the state remained the biggest producer of mosalsalat.

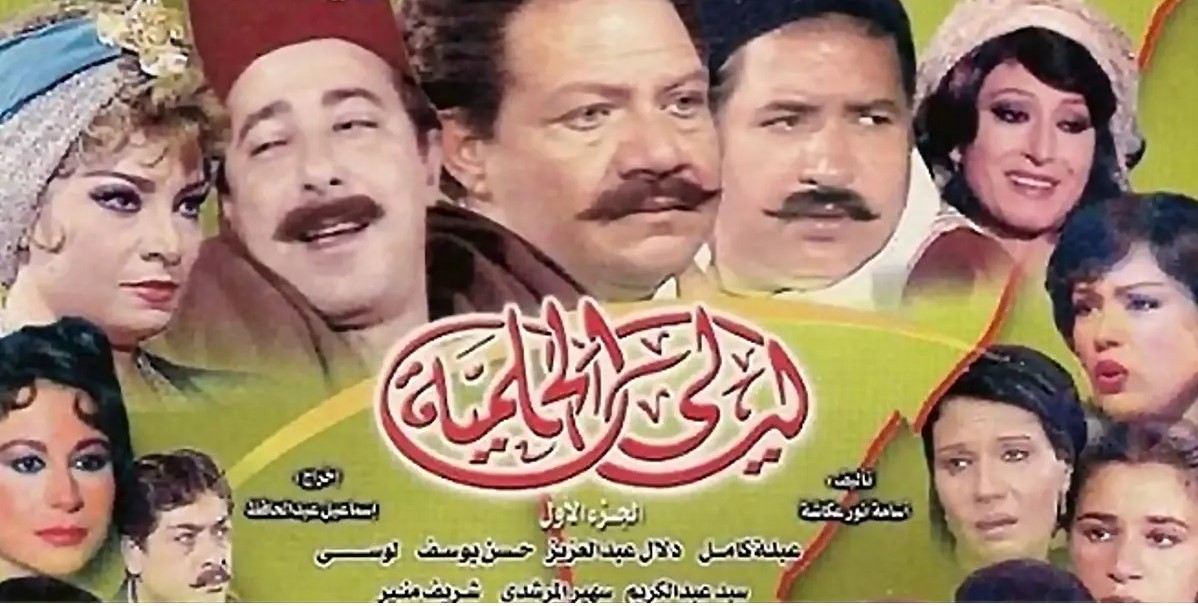

As such, spy dramas like Domo’ Fi Eyoon Waqiha (‘Tears in Shameless Eyes’, 1980) and ‘Raafat Al-Hagan’ (1987) revisited Egypt’s victory in the war against Israel. The most notable work to emerge from the decade was the long-running Layali El Hilmiya (‘Hilmiya Nights’): a historical epic chronicling political and cultural shifts from the late 19th century to the 1990s.

Abu Lughod analyzed the show’s portrayal of women, noting that its female protagonists embodied the struggles faced by women across generations — with characters sometimes overtly praising the freedoms afforded by progressive policies.

By the late 1990s, state involvement in the making of mosalsalat had begun to wane. Increased private investment in media production, the rise of satellite television, and the ensuing popularization of soap operas from competing industries in Syria, Turkey, and India ushered in what Abu Lughod describes as a period of crisis for developmentalism in Egyptian television.

The 2000s witnessed the emergence of more engaged shows expressing political grievances. Examples include the 2007 series adaptation of Alaa Al Aswany’s novel ‘Omarat Yacoubian (‘The Yacoubian Building’), in which residents of the titular building each represent one strata of a deeply unequal society, or 2010’s Ahl Cairo (People of Cairo), a crime drama shedding light on police corruption.

This ethos also bled into comedy, particularly in the years leading up to the 2011 revolution. The 2010 series Ayza Atgawez (‘I Want to Get Married’), for instance, starred Hend Sabry in the lead role of Ola, whose hilarious attempts to find a husband masked a deeper exploration of corruption, class disparity, and other contention issues — foreshadowing the uprising to come.

In its wake, television dramas naturally turned to contemplate the revolution, with many 2012 shows like El Heroob (‘The Gateway’), Taraf Talet (‘Third Party’), and ‘Vertigo’ revisiting the grievances that sparked the uprising.

The Rebirth of State Feminism in Television Series

In recent years, Egyptian television witnessed the resurgence of developmentalism, owed in part to increased public sector involvement in media production. Among its most notable facets is the rebirth of state feminism, seen in the evolution of women’s portrayals on screen.

In 2016, the National Council for Women (NCW) in collaboration with Ain Shams University’s Faculty of Media, released a report stating that gender-based violence and sexist stereotypes prevailed in over half of the year’s Ramadan serials, and calling for better representations.

From there on, the NCW continued to serve as something of a media monitoring force, evaluating the way women are depicted in popular dramas and compiling its findings in a series of studies entitled “Image of Women in Ramadan.”

The following year, shows like Al Hesab Yagmaa (‘The Bill Adds Up’), Ard Gaw (‘Ground, Air’), and Le Aala Saer (‘To the Highest Bidder’), turned their focus to women’s struggle to navigate a patriarchal society. By 2018, the shift had grown more noticeable, with women now comprising more than a third of lead characters in Ramadan serials.

The NCW’s yearly report praised the positive shift in women’s representation, citing Rasa’el (Messages), Layali Eugenie (Eugenie Nights), and Selsal El Dam (Chain of Blood), as three standout works.

In a press statement, NCW president Maya Morsi highlighted the role of the ‘media code for women’ issued by the NCW in 2017 in aiding these developments. This shift in the entertainment realm also fell in line with the launch of Egypt’s thirteen-year National Women’s Empowerment Strategy, which includes points on better media representation.

Does Art Influence Politics or Vice Versa?

In 2018, the shift in women’s representation in Ramadan serials sparked debate among film critics surrounding the reasons behind this change.

Speaking to Al-Monitor, film critic Tarek El-Shennawy put forward the view that women’s prominence in mosalsalat was natural given that the medium is primarily a form of family entertainment. Others, like Magda Morris, believed the efforts of women filmmakers, like acclaimed director Kamla Abu Zekry, to be at the root of change.

Film critic Kamal Ramzy, meanwhile attributed the positive shift to social factors, positing that women were finally reclaiming their rights after decades of marginalization, citing public policy as a key factor. “After 2017 was declared ‘the year of the women,’ producers also started including more visible and more complex female characters in their productions,” he said.

The debate points to the age-old question of whether art actually plays a role in shaping socio-political developments or simply mirrors them.

In a 2004 study of the topic, political scientist Girma Nagesh wrote that “the arts, in all their forms and productions, provide a site from where we can observe and experience aspects of political life that we cannot possibly do in any other way.”

Taht El Wesaya exemplifies this mitigated answer. The show was praised for initiating talks of reform to Egypt’s guardianship law, but to say that the hit series alone bears credit for the upheaval would be inaccurate. The flawed legislation has long been the object of criticism.

In 2021, the National Council for Women, the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights, and Al-Azhar requested that a national debate be held on the law. The same year, an online campaign launched by the Women and Memory Forum called on women to share their experiences with how guardianship law had harmed them and their children.

Building on these different parties’ efforts, Taht El Wesaya was not the instigator, but the straw that broke the camel’s back: through its artful storytelling, the show brought humanity to the impacts of unjust legislation in ways that official discourse could not.

The same can be said of the patriotic serials of the 1960s or the historical epics of subsequent decades. Mosalsalat do not have the power to spark popular sentiment, but they do shape viewers’ understanding of the world in which these grievances unfold and put forward solutions — hence why they have long been a primary tool of developmental policy.

Comments (4)

[…] post Beyond Entertainment: The Social Impact of Egypt’s ‘Mosalsalat’ first appeared on Egyptian […]

[…] Source link […]