Up until the late 19th century, departing from the conventional path of writing in formal Arabic as a poet or writer carried a social stigma within mainstream literary circles. Poetry written in colloquial Egyptian Arabic was deemed a lesser form of art, primarily intended for the uneducated masses.

The term Shi’r, designating poetry, was exclusively reserved for verse written in formal Fuṣḥā, revered as the epitome of eloquence. During the 1960s, a transformative movement emerged in the form of colloquial poetry, seeking to challenge these norms and elevate the status of dialectical expression.

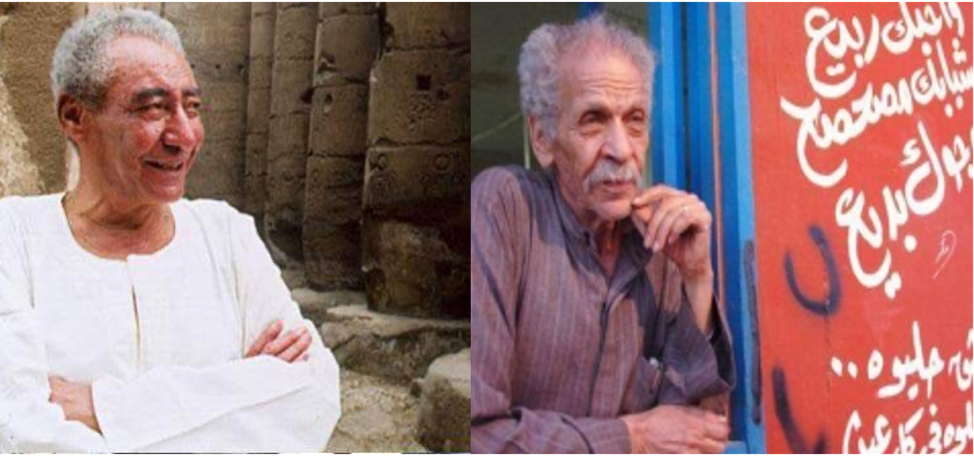

At the vanguard of this revolutionary movement were Salah Jahin and Fuad Haddad, who introduced the term shi’r al-ammiya, or “Arabic colloquial poetry.” Over time, Jahin and Haddad’s fame grew to rival that of many distinguished Fuṣḥā poets.

In the wake of shi’r al-ammiya, a myriad of poets were inspired to write not only in ‘ammiya colloquial Arabic, but also in their native regional Egyptian dialects, such as Fallahi or Sa’idi – the dialects spoken respectively in the rural delta and in Upper Egypt.

While dialect poetry did not attain the same widespread acclaim as colloquial poetry understood by all Egyptians, these poets became unwavering voices for their communities, expressing their experiences through the compelling power of dialect literature.

The realm of dialect literature offers two distinct advantages: firstly, while colloquial poetry brings the art form closer to the masses, dialect literature immerses itself in the unique experiences of specific places or regions. Secondly, dialect literature can transcend the barriers imposed by centralized authority.

In his insightful book, “Strange Talk: The Politics of Dialect Literature,” Gavin Jones explores this very phenomenon, delving into the interplay between dialect and power dynamics, using transcendentalist language theories as his lens.

Emphasizing nonconformity and creativity in language usage, transcendentalists believe that writers who break away from conventional norms can better develop distinctive voices, allowing them to articulate their unique experiences.

The following compilation pays homage to some of many Egyptian dialect literature pioneers that have shaped Egypt’s poetic legacy, reclaiming the rightful place of linguistic diversity within the literary sphere.

Abdel Rahman el-Abnudi

Abdel Rahman El-Abnudi was an iconic Egyptian poet and writer known for his impactful contributions to modern Arabic literature, particularly in the realm of colloquial and dialect poetry.

With his pen dipped in the essence of Sa’idi Arabic, El-Abnudi was a poetic voice that echoed the heartbeats of everyday Egyptians during all critical periods of the country’s modern history. He wove verses that blended social commentary, humor, and raw emotion, inspiring generations of poets to this day.

His renowned collection Jawabat Haraji el-Gutt (Letters of Haraji el-Gutt), an epistolary novel, offers a window into the trials and tribulations of those living on the fringes through an intimate exchange of letters between Haraji el-Gutt, a laborer toiling at the Aswan Dam, and his wife back home.

Fuad Haddad

Fouad Haddad was yet another visionary Egyptian poet whose profound use of the Egyptian vernacular in his writings left an indelible mark on the world of literature. Together with Salah Jahine, Haddad played a pivotal role in founding the shi’ir al ‘ammiya movement.

Despite his Levantine heritage, Haddad’s artistic genius lay in his ability to capture the essence of the Egyptian countryside through his songs and poems in the Fallahi dialect. His verses transport readers to the banks of remote village canals, immersing them into the daily lives and struggles of farmers.

His festive poem Yal Arusa (Oh you bride), written in the Fallahi dialect and later transformed into a song by Ali El Haggar, remains a timeless expression of celebration during special occasions in the Fallahi region.

Hesham El-Gakh

Hesham El-Gakh is a contemporary Egyptian poet born in Sohag and holds a significant place in literature, with poetic creations predominantly penned in Egyptian colloquial Arabic. His debut collection, Al-Diwan Al-Awwal (The First Collection), was unveiled in 2017, after a long history of releasing his work as audio recordings.

El-Gakh’s Sa’idi identity deeply influences his themes, delving into the struggles faced by the people and the youth in Upper Egypt, such as those who migrate to cities seeking better prospects only to encounter disillusionment.

El-Gakh invented the genre of qasida mudaffara, which translates to “braided poems,” a style that combines Fuṣḥā with colloquial ‘Ammiya. In a 2023 interview with Al Hadath, he explains how this style enables him to cater to multiple target audiences within the same poem.

Among his works, Akhir Ma Hurrifa Fi Al-Tawrah (The Last Alteration of The Torah) stands out for its exceptional fusion of Fuṣḥā and Sa’idi Arabic, a combination different from his other braided poems which typically blend Fuṣḥā with ‘Ammiya or ‘Ammiya with Sa’idi.

Ahmad Fouad Negm

Ahmad Fouad Negm was a renowned Egyptian poet, revolutionary figure and torchbearer of social consciousness. Born in Sharqia, Egypt, Negm grew up in a working-class environment, which strongly influenced his poetry and worldview, earning him the title of the “poet of the people.”

Throughout his prolific career, Negm collaborated with prominent musicians like Sheikh Imam, creating a fusion of poetry and song that became an anthem for the Egyptian revolution. Though he mostly wrote in ‘ammiya colloquial Arabic, a significant portion of his poems delve into the stark reality of poverty and the struggle for survival faced by the rural working class in Egypt, with imagery and analogies directly drawing from the farmers’ daily life and his Fallahi heritage.

Sayed Hegab

Sayed Hegab was a celebrated Egyptian poet and writer, renowned for his exceptional achievements in ‘Ammiya poetry.

Born in a fishing town on Lake Manzala in Daqahliya, his poetic voyage commenced in childhood, as he roamed with fishermen in pursuit of their age-old verses. Over time, he immersed himself in the fishermen’s world, becoming a poet who eloquently spoke their language and grasped the essence of their way of life.

In later years, Hegab released his debut poetry collection, Sayyad we Geneih (A Fisherman and a Pound), offering a heartfelt portrayal of the fishermen’s lives, recognizing them as a microcosm of Egyptian society, and making their stories a powerful lens through which to view the nation’s rich heritage and collective identity.

Abdulati El Fardy

Abdulati Mohamed Abubriwah Al-Fardi, a Bedouin poet from the Afrad tribe, embodies the rich tradition of Bedouin poetry, where verses are revered as historical records.

His poems cover themes from World War II’s onset in 1939 to reflections on Bedouin migration in 1940 and encounters with Libyan migrants in Maryut. Written in either Bedouin or ‘Ammiya dialect, his poetry captures the essence of his community’s experiences.

Typical of Bedouin poetry, Abdulati’s works are primarily passed down orally, limiting their wider dissemination and accessibility in written form. However, his legacy lives on through his son, Arafa Al-Fardi, who passionately upholds the family’s poetic heritage.

Arafa actively fosters cultural events, gathering poets, writers, and intellectuals at the Cultural Center in Borg El Arab, Alexandria, allowing the flame of their poetic tradition to shine ever brighter.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (0)