By Enas El Masry, originally published on Community Times

Growing up in the early 90’s, there were barely a few things as sacred as religion to live by as a child — on top of which of course, Disney’s 1994 animated film The Lion King. “Welcome to our humble home,” Timon told Simba as he introduced him to the jungle, “We live wherever we want.”

In the following 20 years, my generation, as did I, grew up learning a bit more about the world, yet still holding on to our Hakuna Matata philosophies somewhere in the back of our minds. Yearning to live up to the free spirits that some of us are, it wasn’t long before we realized it’s not that easy to just “live wherever we want.”

Disillusioned with the allure of the big cities and the promise for a better tomorrow, a minority of youth who dare to question the status quo, but mostly dare to live outside the boundaries of the norm, have started turning their backs on the plastic life of the city, hoping for a life fueled with more meaning and value than keeping up with the pop-culture and its consumerist behavior.

As the sound pollution of everyone else’s ideas on the good life muffles their aspirations, a minority of Egyptian dreamers continue to slave away in silence, taking refuge in the few days they steal in the embrace of nature, dreaming of the day they break free from this urban, corporate-run life.

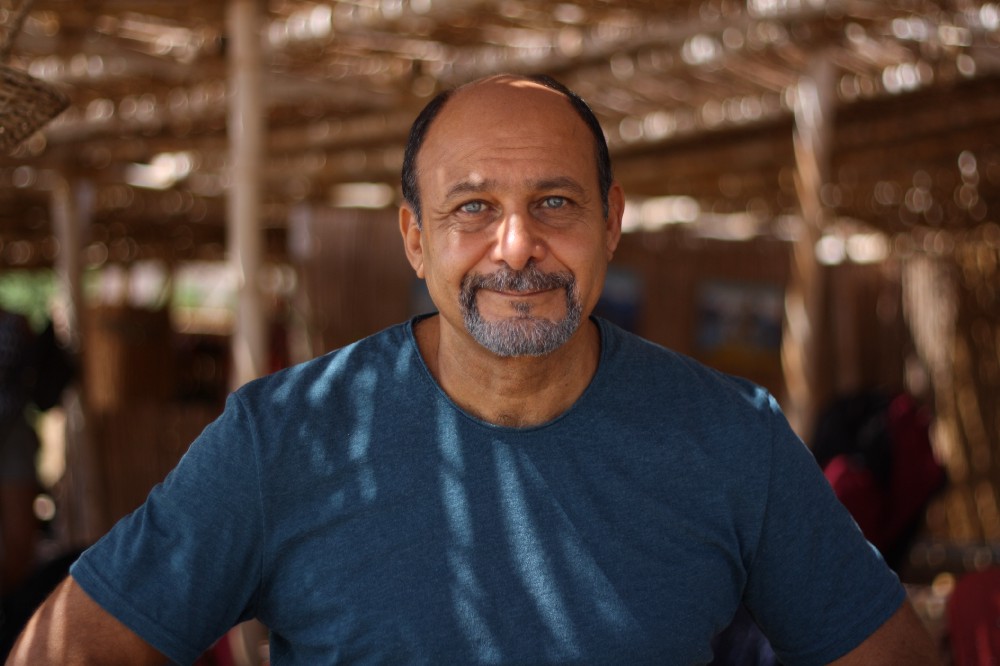

Genuine as they are about their dissatisfaction with the urban life, many remain paralyzed with fear that life outside the big city may not actually work. However, two pioneers who have established life in the middle of nowhere have something to say about that. Sometime around the early 80’s and early 90’s, Sherif el-Ghamrawy, owner of Basata Eco-Lodge, and Maged el-Said, owner of Habiba Community, decided to step outside the big cities and move their lives to Nuweiba, South Sinai. Decades later, they don’t have a shred of doubt that they made the right choices.

What Lies Beyond the Mandates of Norm

“Any community starts with manpower; with people like us who decide to leave the city. The whole point is to take action,” says Said. “The part about fear; what will I eat, how will I live, and all of that, those are just illusions that we create in our heads because we’re in the system, and those who are in the system cannot see other paths.”

Concerned about the governing values of the big cities, both Ghamrawy and Said warn against the dangers of living by the book. “The grand issue is that we have glorified the word ‘must’,” explains Said. “I must study at this particular school or university, I must dress as such and I must marry someone who’s this or that.” Eager to adopt this alleged one-size-fits-all societal mold, many surrender at a young age to blindly living by the book which dictates various aspects of our lives, giving little to no regard to personal capabilities or aspirations. Despite individual differences which span everything, the youth are inevitably prepared for the same journey which takes them through education, getting a well-paying corporate job that covers the unnecessarily high expenses of life, and from there on, life becomes more or less a loop.

“Between the ages of 25 and 50, everyone’s chasing after a mirage called ‘career’,” claims Said. “Whenever I ask [my visitors] what they would like to do with all that money, the answer is usually something like, “buy a house by the sea where I can retire.” Well, why don’t you live by the sea your entire life then?”

While it sounds almost dreamlike, fulfilling this dream starts at one pivotal point: knowing your priorities by heart. “Priorities may differ, and they’re all right,” Ghamrawy emphasizes. “But what is wrong is to blindly follow the norm if it doesn’t suit your aspirations.” If you’re best cut for the city life, then there is no need to pursue self-realization elsewhere, however, if life in the concrete jungle defies your values, then you should probably start building steady grounds for your move.

“I’m not asking people to just quit everything and make haphazard decisions, but you should at least be aware of the life you’re leading, and to start preparing the grounds upon which you can stand — how to not carry on living among the crowd,” adds Said. “Such steps can include not buying an apartment worth millions in the heart of the city.”

Once that is achieved, he advises the youth to give themselves the time to learn from those who have walked their desired path before them. “We’ll offer you a comfortable place to stay [at Habiba], and then you can go work at our farm or any of the other neighboring farms owned by the Bedouins,” Said mentions suggesting one model. “You’ll also get to meet like-minded people, and they are a lot by the way, but you’re scattered with nothing to bring you together because each is trapped in their own whirlpool of challenges.”

Nonetheless, as bold as it is to give up the luxuries and assumed security of the city to move out, Ghamrawy stressed that the driving force behind taking action makes a concrete difference.

“There’s a huge difference between wanting to escape the place you’re in and between having the strong desire to go to a particular place. If you want to escape, then any other place will do,” he clarifies. “When your sole driver is escapism, chances of success become much thinner.”

With steadfast resolve to leave Cairo, both Ghamrawy and Said started their journeys by scanning the entire country for the new place they would like to call home.

“Although I lived in a Maadi villa with a yard, I felt like I was living on a lettuce leaf in a dumpster,” said Ghamrawy. “I traveled all over the country and I was awestricken with its beauty. Egypt is not Cairo; Egypt is Egypt, and I decided I had to emigrate from Cairo to Egypt.”

While younger Ghamrawy fell in love with the entire country, from oases to deserts, the Nile and the mountains, he knew at heart he had to live by the sea. At 26, he had started the legal paperwork to settle in Basata, a move he finalized by the age of 30.

Similar but different yet, Said’s journey to Nuweiba took off on a different note. After graduating from the Faculty of Alsun in 1979, he traveled to Italy where he met and married Lorena. After having their first baby, Yasmine, they decided to return to Egypt. “Since she was about to move her entire life to a new country, we roamed Egypt so we could pick the place she’s most comfortable with,” Said recalls. “And we finally settled in Sharm el-Sheikh.”

“It wasn’t that I was urged to escape the city, but instead, my mentality and philosophy grew and shifted as I stepped away from the city by time,” says Said. “At that time, when I made my move to Nuweiba, I hadn’t really grasped the full picture of what I was doing. I only know that now, looking back on my journey so far.

“However, if I had found someone 20 years ago to tell me what I tell the youth now, things would have been so much different for me.”

Setting Up Life in the Middle of Nowhere

“Unfortunately, we are really lazy and we are afraid. We work in corporate so we can feel safe. We work in the government so we can be insured,” adds Ghamrawy. “Whoever wants to leave the city has to put in the necessary effort. It’s fun effort.”

Having walked down this path in a time when resources were slightly less accessible, Ghamrawy and Said learned how to forge their own paths despite the recurrent challenges. “The real obstacles are in our heads,” says Said. “I see solutions not problems, and that’s how I deal with life.”

For over 30 years of running Basata, Ghamrawy has barely seen any support from the government, including basic services such as electricity and a drainage system. Despite the lack of basic services and infrastructure, he simply learned how to find his way around challenges, no matter their nature or magnitude.

“We have to fully understand that this country is ours and that we are the decision makers, not the government,” Ghamrawy exclaims. “Throughout Mubarak’s 30 years, we had grown used to the government being the mama who does everything. No, we are the mama. We create, and the government executes and validates.”

Persistent as he is, Ghamrawy still faces the burden of nationwide issues such as centralization, which adds unnecessary complexity to otherwise simple matters. Not only does it require him to travel to the capital city or the nearest major city, al-Tur, which is 350 kilometers away, for official paperwork and legal issues, it has also kept service providers such as plumbers, electricians, carpenters and others from spreading out across the country.

“In distant, isolated places in Egypt, the least effort stands out because these places have very little competition, and they have a very high need for what people have to offer,” explains Ghamrawy. “Out here, all the skills and capacities are needed, whether you’re a web developer, engineer, or whatever it is that you do,” adds Said. “Instead of slaving away for big companies that don’t care about you, come invest your time and energy in a community that will surely flourish from your skills and knowledge.”

Giving Back to Community

Aware of the amount of positive change they were capable of bringing about, Said and Ghamrawy have remained since the start keen on safekeeping their new hosting communities from drifting away from their identity and culture.

“Over 30 years of living here have allowed me to build strong relations with the local men, women and youth, and it has helped me live their issues,” says Ghamrawy. “I can’t enforce anything on them, because now, I am one of them.”

Through his NGO Hemaya, which he established 20 years ago, Ghamrawy has been catering for many lacking needs in the South Sinai region. The NGO’s ongoing projects include sanitary services for Nuweiba and Dahab, in addition to collecting the strip’s garbage from Taba to Dahab, which is separated, compressed and sent to Cairo for recycling. Other services include the maintenance and sanitation of both hospitals in Taba and Dahab. Through Hemaya, Ghamrawy has rented out two houses in Nuweiba that serve as a culture center, kindergarten and a hub for women-tailored workshops.

Meanwhile, Said has taken a rather different approach to serving the community, which revolves on the most part around integration. In 2007, he established Habiba Organic Farm and Habiba Learning Center, which have both become beacons and hubs for knowledge exchange for the locals and visitors alike. Promoting volunteer tourism as an active member of WWOOF, Said invites his visitors to pair their vacations away from the city with a chance to enrich the Bedouin community of South Sinai, either by teaching at the learning center, or working on the farm. Other programs include academic work for undergraduate and post-graduate researchers.

Raising a Generation of Free Decision Makers

![Young hikers await sunrise at the summit of Mount Sinai [Jebel Mousa]. Credit: Enas El Masry](https://egyptianstreets.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/CT6.jpeg)

Although the youth bear the consequences of their choices, one can’t overlook the role parents play in hindering their freedom to follow their own paths. “This is how our generation was raised. We never stopped to think, we were just functioning,” says Said. “That’s why when we step outside the crowd, we get more room to think and weigh out the best solutions.”

In order to break the pattern, Said and Ghamrawy were keen on giving their children the freedom to forge their own paths. “I didn’t want to repeat what my father did, acting like [my children] are my employees until they graduate, and then they’re free to do whatever they want to do,” adds Said. “We all keep saying how we’re doing all of this for our children, which is a big lie. I say I do this for Maged, and my children can do whatever they want to do for themselves.”

As valuable as his ideals are, they are only words unless he practices what he preaches. Acknowledging the difference between education and learning, Said gave his youngest son the freedom to drop out of college. However, at a much younger age, he has prompted his children to experience life first hand through travel and work.

“When we are aware of such differences, when we say them out loud, believe them and apply them, that’s when change starts to take place,” he explains.

As for the Ghamrawys, their primary concern was to stick together no matter what. Today, Sohaila, Ghamrawy’s eldest, is an engineering student at the American University in Cairo (AUC), while Faris, his youngest, is in his final year of school. Both of his children have studied their entire life at the school of Basata, a school that provided the Ghamrawy children as well as their Bedouin peers a chance to receive the finest education.

Today, Ghamrawy looks around and he sees many examples of youth to be proud of, and community influencers who, only yesterday, were children playing with his own children on the beach. “If we keep thinking and waiting around for something to happen, time will fly by and we will do nothing,” says Ghamrawy. “Whoever wants to start should start now. Start with whatever your potential can help you achieve. It’s okay to make mistakes, you won’t die, but it’ll make you stronger and wiser in the future.”

Comments (0)