“Only my husband, father, and brother are allowed to hit me,” those were some of the first words of Reda, played by Lina Sakr, a theatre student at The American University in Cairo, in her live-streamed one-woman show of Alfred Farag’s Al-Mishwar al-‘Akhir (The Last Walk).

Farag’s second-to-last play, written and performed in Arabic is, as Theatre scholar Dina Amin writes, “concerned with the plight of a battered woman from the struggling classes of Egypt.”

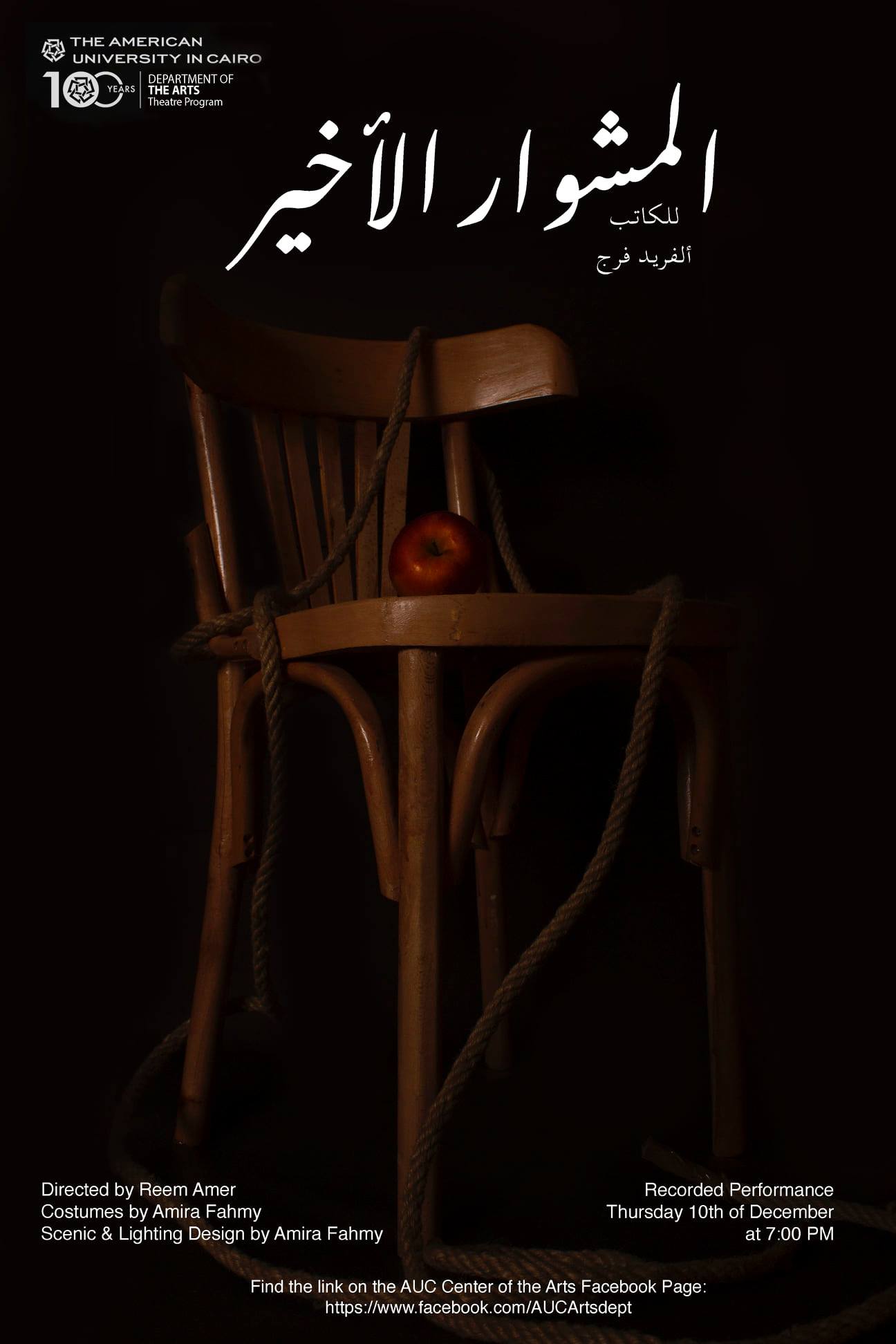

Directed by Reem Amer, the play addresses issues of domestic violence, physical abuse, illiteracy, and poverty.

Single-handedly led by Sakr, the emotionally-charged monologue tackles domestic abuse in Egypt when the character is seen tied up by her abusive husband. However, the most eerie aspect to her situation is her continued devotion to her husband, who she constantly refers to as Habibi (my dear), despite him leaving her and taking her kids after tying her up.

The simple yet strategically vivid set, designed by Amira Fahmy, leaves room for the imagination for the viewer, with Reda sitting in a dark room, tied up, with enough spotlight to barely light her up. To her right and left appear simple props when prompted, such as a chalkboard and a table.

The lightning, designed by Sherif Daly, is so seamless that it’s surprising when the chalkboard is seen in the back as we are so immersed in the character against the pitch-black background.

The narrative changes throughout the play with Reda changing her story, in clear psychological distress, of how she got tied up. “He tied me up and forgot to untie me”, “he took the kids and left, of course, he left me”, “I deserve this”, “God will solve it”.

Reda’s undying, and often misunderstood, faith in God, is a sample of many Egyptian women, who confuse unconditional faith with patience in unjust situations of abuse in domestic life.

It is difficult for the viewer to ignore a woman dressed in a men’s galabeya with her hands tied up with rope to her waist, but the galabeya is never addressed and remains a question in the viewer’s mind.

Sakr’s tones skillfully change from a nostalgically joyous mother and wife, to an angry and disturbed woman. She shows signs of forgetfulness of her situation, and of the detrimental effects of the abuse on her mental effect.

Starting to process her loss, Reda’s haunting looks take the viewer by surprise, from sudden laughter to anger.

The play impressively wraps up an entire societal debacle spanning centuries in a single twenty-minute monologue, with few props and a near-bare set.

Farag’s lesser-known 1998 one-woman monologue is a painful look at the internalized blame and misogyny that is placed on women in Egyptian society. With a glaring takeaway, the virtual one-woman show does not seem to lack much despite the untraditional online setting, with Sakr never failing to capture the viewer’s attention regardless of the distance.

The live recorded one-woman show from Thursday, December 10, which was a student production, is available for viewing on The American University in Cairo’s Center for the Arts Youtube channel.

Comments (0)