If you walk down Fouad street in Alexandria, at the crossing with Sofia Zaghloul street you will see the bright movie posters adorning the walls of the famous Cinema Amir. But if you look down, you will also see the mesh steel gates habitually blocking the entrance. While this isn’t true every day, more and more often the cinema remains empty and closed. It is a rather poignant image: the derelict cinema, once again out of bounds to passers-by, a nod to a forgotten era; and the waning institution of Egyptian Cinema.

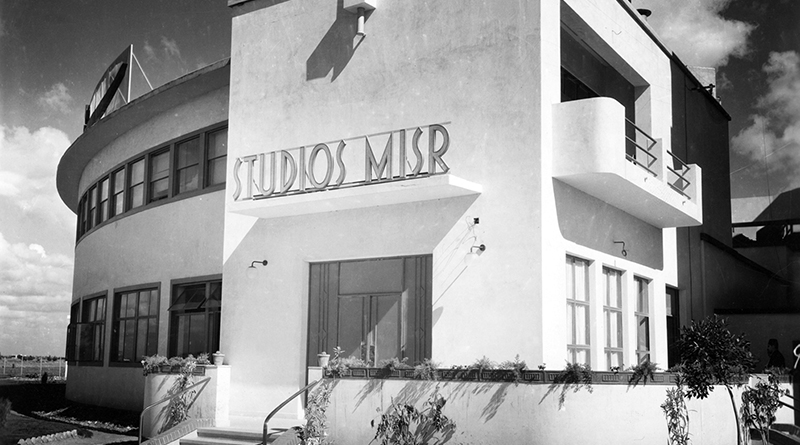

The Egyptian film industry, at least economically, seems to have had its heyday in the middle of the last century, when the industry produced upwards of 100 films each year. Currently, the ‘Hollywood of the Middle East’ struggles to produce more than 30 films in a year. In 2019, the industry made a total of $72 million in box office ticket sales. While this is a small figure in comparison to centres like Hollywood and Bollywood, it does remain the regional cinematic hub in the Middle East, according to the Egyptian Centre for Economic Studies. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit; around the world it became very difficult to film, produce and distribute movies, and Egypt was no exception.

During Eid al Adha, a holiday famous for the mass distribution of films in Egypt, only one film was released in 2020. By comparison, in 2019 there were cultural articles naming the ‘top five’ Eid al Adha films to see.

The film in question, a sci-fi comedy called Al Ghasala (The Washing Machine) failed to make waves, despite the lack of any competition. From May 24th 2020, cinemas closed as part of the strict lockdown measures. With no one allowed to go to the cinema, movie production halted as well.

Mohamed Hefzy, an Egyptian producer and president of the Cairo Film Festival told AFP last year that fewer films were being produced as “dependence on movie tickets sales [became] too risky,” as people increasingly stayed home.

The lockdown had a direct effect on the entire cinematic industry as well. It became impossible and even dangerous to have sets of 100 people operating while the virus was spreading rapidly. Actors, technicians, runners were getting infected on set. In human terms, up to 60 percent of workers in the 500,000 person industry were liable to job losses last year, as they were on informal contracts, according to a report by the ECES.

“This year has been a great loss to the movie industry in Egypt,” the actor Sherif Ramzy said in an interview, also with AFP. “The industry came to a complete halt for months.” Ramzy lamented the decision to only open movie theatres at 25 percent capacity last summer: “even the partial reopening of theatres has not helped get the ball rolling.”

Yet, many see the pandemic as little more than a catalyst for bigger problems facing the industry, in Egypt and around the world.

Today, films and video content are consumed in a different, more flexible way, that doesn’t involve cinemas. Even in a country where the vast majority of the population doesn’t own a computer, consumers are generally turning away from traditional entertainment means such as going to the cinema or watching cable for on-demand streaming services such as Netflix, Hulu and WatchiT. Even in 2015, 68 percent of Egyptians surveyed said they accessed movies online. In the Middle East, particularly in Egypt, Netflix is growing in popularity, as is Shahid, WatchiT. This transition was “a natural development” according to Hefzy, but the pandemic “only hastened it.”

While this may be negative news for cinema owners, it by no means marks the end of Egyptian cinema, or at the very least Egyptian programming. The new Egyptian streaming site Egypt Watch iT offered over 65,000 hours of Ramadan series last year and reported an 89 percent jump in users. Egyptians are still watching movies and television, just in different ways.

What is also very encouraging for the industry, is a certain ‘cinematic patriotism’ among the Egyptian population. The vast majority of Egyptians prefer to watch Egyptian films in comparison to films from other Middle Eastern countries, or indeed from the west: the highest proportion by far in the Middle East. Despite Egypt having the biggest population in the Middle East, non-Arabic films only earned $22 million at the box office; in the UAE they earned $183 million. By comparison, 96 percent of Egyptians surveyed in 2018 said they preferred films made in their own country, compared to just 55% of UAE residents. This may change due to greater access to foreign films through streaming services, but the statistics remain favourable at the moment.

There is also more immediate positive news for the industry, with the return of film festivals in Egypt: the Ismailia Documentary Film Festival is kicking off in June 2021, and the big international festivals in El-Gouna and Cairo insist they plan to take place later this year.

Equally, on an international scale, a film by the Egyptian filmmaker Ayten Amin called Souad will screen next week at the Tribeca International Film Festival in New York, blazing the trail for young Egyptian filmmakers internationally

The pandemic has been a tough period for the film industry around the world, including in Egypt; and this period isn’t over yet. For cinemas, a return to pre-pandemic times may not be possible, as people shun more conventional and formalised ways of watching films and television for their laptops or their phones. A shift that COVID has accelerated.

Yet, there is a nostalgia for the silver screen that may just save them for a little longer. Streaming sites “cannot substitute movie theatres,” insists Hefzy, “the cinema experience remains to be unique and important and it should be preserved.”

Comments (3)

[…] The Final Curtain: Can Egypt’s Film Industry Survive COVID-19? […]

[…] Source link […]