Standing at a kiosk in the bustling neighborhood Mohandessin, a clerk offers someone a lukewarm soda, loose change, and a nokta: a brief joke punctuated with a smile and a snappy punchline. Little do either of them know that this nokta has a long road ahead of it – soon, it’ll be a dinner party talking point, and a workplace icebreaker.

Nokat – or jokes – are the bread and butter of the Egyptian personality; from long, mastic-stretched riddles to quick jabs, locals have transformed humor into a cultural hallmark. Egyptians are not the first to use humor to “rebuil[d] the [understanding] of relationships” or manage stress levels, but they’ve certainly earned the title of Sha’b Ebn Nokta: a population raised on feel-good, quick comedy.

“It’s a nokta!” Ahmed El Abd (57, engineer) laughed. Being Egyptian, El Abd grew up with this humor. “If it’s not short and biting, then who cares? Sometimes it’s elet adab (in poor taste), but that’s part of the fun.”

The Journal of Cultural-Historical Psychology explains that jokes are vehicles of emotion, indicative of cultural narratives and biases; humor exposes the honest truth about the person using it. El Shorouk News dresses up the idea, remarking that a joke in Egypt is not just a simple gesture, but a “weapon” of sociocultural and political critique.

El Abd was asked about the difference between political nokat and cultural ones, and his answer began with a joke. “I feel like I’m at a qesm (police holding) and what happens to me depends on my answer.”

“We’re more entitled to political jokes, because we’re sha’b ghalban (a poor population), but at least we’re not dealing with the racist ones anymore. It wasn’t just the Sai’di’s, you know. It was a lot worse, there were Sudanese jokes, too,” he continued.

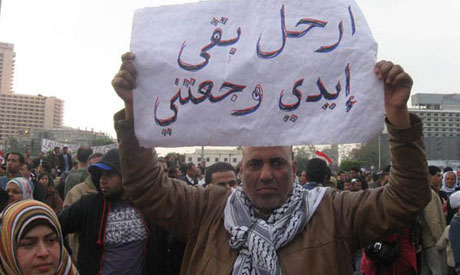

In an attempt to ridicule social and political spheres without facing persecution, many activists hijacked the nokta to vent their frustrations. Jokes about Mubarak being glued to the seat of power were as commonplace as seeing the Egyptian flag hang limp from balconies, and humor proceeded to get more daring until the country was able to stabilize after years of unrest.

“[Egyptians] are like that, I guess,” said Hania Taher, a 26-year-old master’s student, in a Zoom call with Egyptian Streets. “We have a knack for taking the piss out of things, especially when in good company. Guess it just [differs] what type of jokes you find funny.”

When asked to elaborate on her own tastes, Taher took a moment to think. “It’s hard to pin down [but] relatability is a big factor I think.”

Relatability has, indeed, made a bizarre addition to the nokta: self-deprecation. Egyptians – whether through Sa’idi jokes or their continuous, street-savvy mocking of the government – were not in the habit of mocking themselves directly. It’s a global phenomenon, where youth who struggle against authority and control, choose to put sardonic twists on their humor.

By doing so, they’re able to critique much larger, more dangerous institutions without being penalized for it. A nokta about taxes, one about inflation, another about the price of gas and the ‘I’ll help you, if I even manage to help myself’ mentality: the nokta is part of Egyptian millennials speaking out against perceived wrongdoing, in an otherwise silently critical society.

According to cultural researcher Kim Koltun, Millennials are the first generation to truly struggle with debt, unemployment, poverty, and self-judgement on a grander scale. This, unsurprisingly, has had a profound impact on the self-esteem and self-awareness of many young people.

And in true Egyptian fashion, Egyptian youth have chosen to make fun of it. From workplace memes, to digging up old, relatable movie screen-caps, young people have decided to take the brunt of their own mocking, to lighten the blow.

The nokta is elemental to Egyptians of any given generation, and incredibly indicative of the social climate they reside in. From themes of latent classicism and luxury-hounding, to an era of jadedness and devil-may-care humor: the nokta is a homemade mechanism for it all.

Comments (8)

[…] يطلق على المصريين “شعب ابن نقطة“(الأشخاص الذين يحبون المزاح) ، كان معروفًا أيضًا […]

[…] Egyptians are called “sha’b ebn nokta” (people who like to joke), he was also known for his unparalleled sense of humor. Most of his […]