Sleek hair. A cropped, clean background. Carefully and strategically themed pose. Visually symbolic colors.

For just a few seconds, and through just one image, the identity of a nation is defined through a figure.

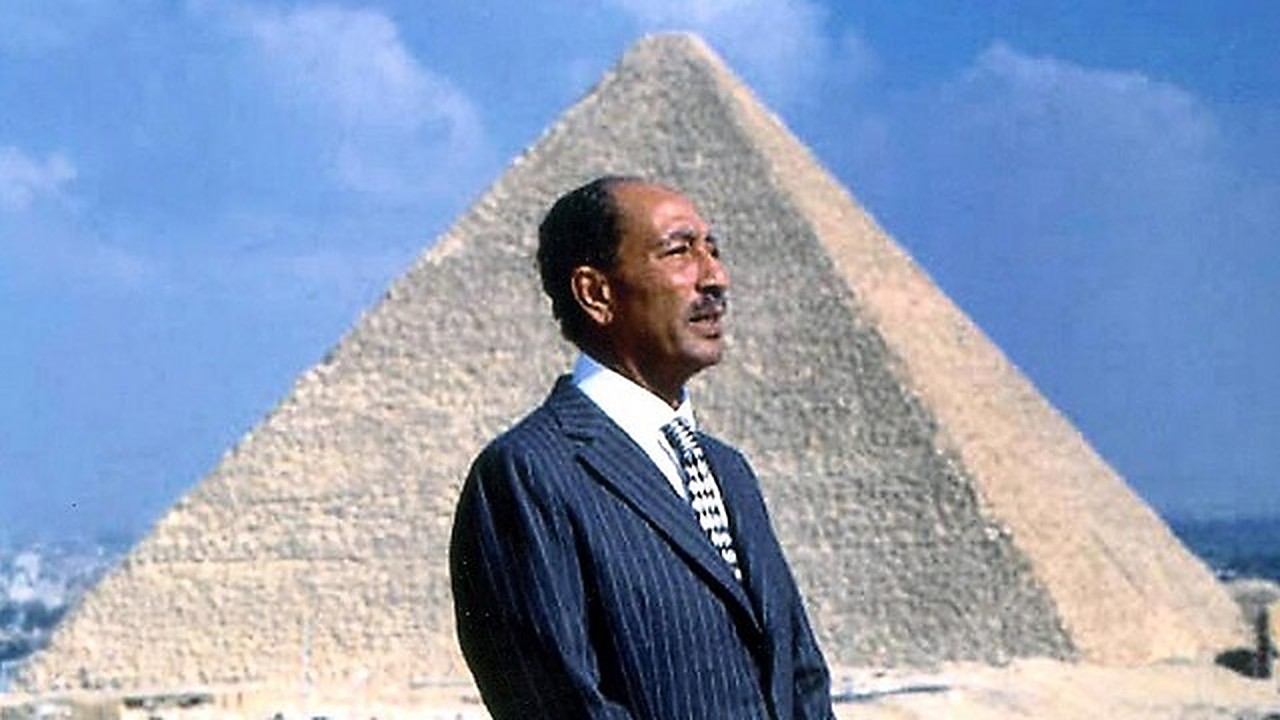

With the Great Pyramids in Giza as the backdrop, former President Anwar El Sadat was once pictured by American photographer David Hume Kennerly standing tall like a modern pharaoh, exuding power, independence, and authority. The power of the image did not lie in any real story, but simply in its aesthetic and portrayal of modern Egypt.

While the phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words” is often used to symbolize the power of an image, when it comes to political photography, sometimes there is no need for any story, meaning or words. What is far more important is how the visual – the glitzy image – constructs and manufactures a nation’s identity or a politician’s personality, and the other way around.

It all truly began with President John F. Kennedy (JFK) in the 1960s, as it is often said that JFK created a presidency for the “television age”. During the first-ever televised general-election presidential debate, JFK and Nixon illustrated quite clearly the effect of an image in politics.

The real winner was not JFK, but in fact, the televised appearance of JFK: handsome, articulate, poised and confident, which juxtaposed with Nixon’s awkward, dull and gloomy appearance. “Fire the make-up man,” a Nixon supporter told Nixon’s press aide, “that man cost us the election.”

But, how could an entire nation’s politics depend on a stylist and a make-up artist? While there were many other factors involved in JFK’s win, what was clear from that day onwards was that the superiority of the image in politics could no longer be ignored.

Like JFK, former President Gamal Abdel Nasser also created his own image of a presidency. Egypt, which was still young and newly independent, was identified through his charismatic, picture perfect smile that appeared in all of his images. Egypt was seen through Nasser, and Nasser was seen through Egypt.

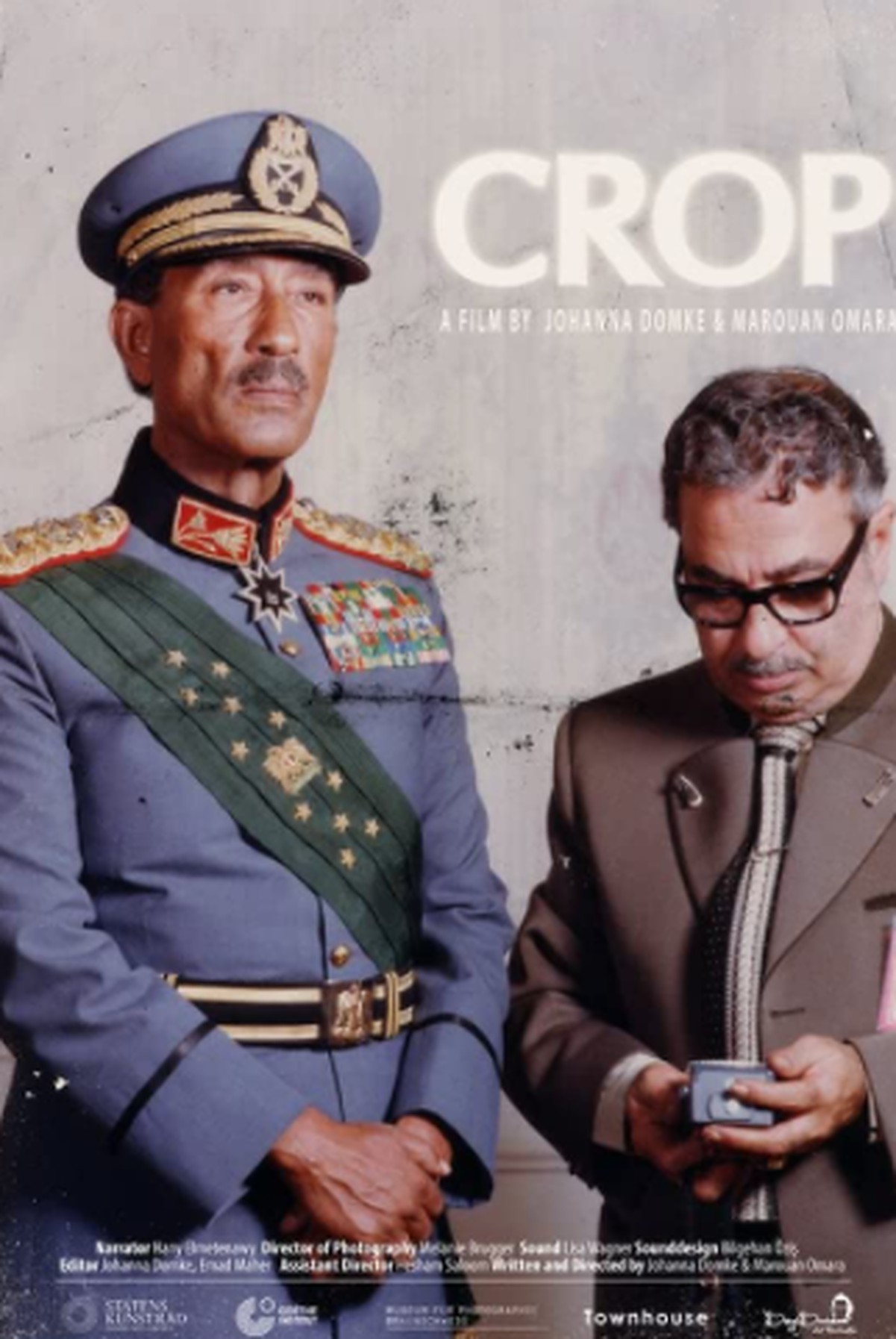

Understanding this bizarre relationship between the president, the nation, the people and the image is explained most clearly in the Egyptian documentary ‘Crop’, which was screened at this year’s Film My Design (FMD) film festival at the beginning of February.

Directed by Marouan Omara and German video artist Johanna Domke, it is a documentary for our time, despite being released nearly a decade ago, in 2012. The experimental film depicts the unfiltered, the uncropped, and the unfined image of Egypt through the eyes of a photojournalist.

Filmed entirely within the offices of Al-Ahram, one of Egypt’s oldest newspapers which represents the heart of the country’s state-controlled media, the documentary challenges the viewer’s need and hunger for glitzy and aesthetically pleasing views, and strips down anything unreal.

CROP – Trailer from CROP on Vimeo.

Screens have always sold us an escape from reality, whether it is our television or mobile screens, but in ‘Crop’, the irony is that the screen becomes – for the first time – reality. Throughout the entire documentary, the viewer experiences two different worlds: a voiceover narration depicting how an institution practices strict control over Egypt’s ‘image’, and raw and unfiltered visuals by a film director that practices zero control over framing the everyday functioning of employees in that same institution.

This paradox, between the voiceover and the visuals, not only symbolizes the contradictory life we live in, between the real and unreal world of screens, but also raises the question: do we care more about the story or the visuals? The substance or the glamour? The real or the unreal?

When the visuals of the documentary become too dull and depressing to look at, it is overshadowed by the heartful account of the photojournalist’s story and his experiences working as a photographer for the government, which eventually bring about more depth and beauty to the gloomy scenes that are seen on the screen.

The voice of the photographer is usually heard through his images. But, in this case, his voice was heard through his story of three presidents and how their images influenced not only their perception of reality, but also Egyptians’ sense of reality. From the times of former President Nasser, the photojournalist recalls how Nasser used the image to portray his connection with the Egyptian population, and to push his own story and vision. The image was used as a medium to communicate, to connect, and to create a sense of belonging.

Egypt’s identity was shaped through Nasser’s own political vision of independence, nationalism and socialism. The vision mirrored the images, and accordingly, it was the image of Egypt in his eyes. Nasser also understood the value of his own image, and paid close attention to how he presents him in his images as fatherly, warm and friendly. There was a touch of intimacy in all of his images, which the photojournalist points out made it easier for people to connect with him.

Yet, this intimacy with the president came at a cost of excluding others in shaping the image and identity of Egypt. Like Nasser, President Sadat also liked to use the power of the image, and was often pictured with his family in intimate settings. Nonetheless, he increasingly cared more about his image than his connection with the people. The ‘real’ Egyptians were often excluded from the image, and in turn, felt disconnected from the president.

By the time of Mubarak’s rule, the obsession over creating a filtered, cropped image of Egypt become so common to the extent of self-censorship.The photojournalist looked back at his own experiences of feeling hesitant to capture any photograph that looks too real, and always tried to find a ‘positive angle’ or filter to beautify the image. “Your job is to protect Egypt’s image,” he was once told by a citizen, who refused to be photographed. “My photograph will harm Egypt’s image.”

Image is reality, but it took time for Mubarak, and the political regime, to learn that lesson. By the time of the 2011 revolution, it was already too late. People in the streets were taking their own images – they accepted their unfiltered images, and there was no longer room for cropped or glitzy images.

The revolution’s images sparked a self-realization. Egypt was seen through many angles, perspectives, and different viewpoints. People were longing to be included in the image again – to be part of the story. In the end, the documentary sends the message that for political photography to continue to have an impact in our world, it has to go beyond the glitz, and focus on including everyone’s story.

Comments (0)