“أنتِ جميلة كوطن محرر وأنا متعب كوطن محتل”

– مريد البرغوثي لرضوى عاشور

“you’re as beautiful as a liberated homeland and I’m as tired as a colonized one.”

Mourid Al-Barghouti to Radwa Ashour

Some of the most epic and powerful love stories belong to those who have given their lives to a political cause. On the top of that list in living Arab history are Mourid Al-Barghouti, the Palestinian poet, and Radwa Ashour, the Egyptian literary.

In 1944, Mourid Al-Barghouti was born – a new addition to the large Barghouti family – in Deir Ghassana, near Ramallah, Palestine. At only four years old, Al-Barghouti and his family were forced to leave Palestine, following the Nakba of 1948.

The family, large and united, were forced apart, scattered across the world, only reuniting in a single city for a few days or a week at the most every few years. Fate intervened, sending Mourid to Egypt after his acceptance into Cairo University to study English Literature.

In 1946, Radwa Ashour was born to lawyer and literature enthusiast Mustafa Ashour, and poet and artist Mai Azzam, in a house in El-Manial, near the center of Cairo. Born only a year after the end of World War II and a few years before the Nakba, in such a household, made escaping politics impossible for young Radwa.

Surrounded by such upheaval, including the movement of the Free Officers, which worked to overthrow British rule in 1952, during her school years, Radwa grew up enamored with history, politics, and literature. It made sense that her path led her to the English Literature department in Cairo University.

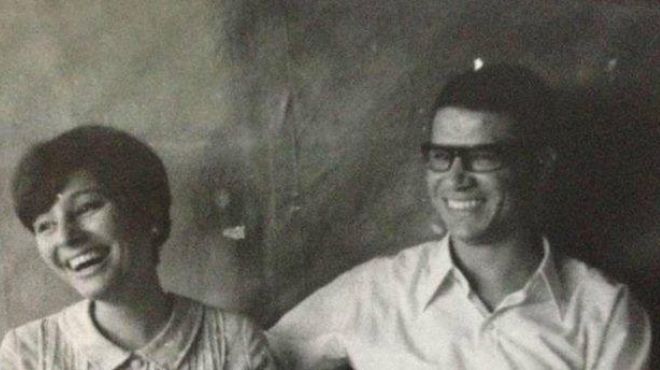

Their story begins on the steps leading up to the central library in Cairo University, where a young Mourid stood reciting poetry, his smooth tenor ringing out strongly, if quietly, ensnaring the heart of a young Radwa, who, after hearing his poetry, swore off of writing any. Radwa said, at the time, “الشِعر أحق بأهله” (poetry is more deserving of its people).

Radwa often says that on that day, his poetry pierced her heart and filled her being, entrancing her. A friendship was sparked between the two cultured and politically active youths, each deeply concerned with the state of affairs of their respective countries, and by extension, each other’s.

Upon his graduation, Mourid moved to Bahrain to work, and Radwa remained in Cairo, finishing her bachelor’s degree. Despite the distance, Mourid and Radwa continued to be friends, exchanging letters often, becoming each others’ closest confidants.

They would often reminisce about a conversation that they had on the university campus in the earlier days: When Radwa told Mourid he would become a renowned poet, he responded by asking: “what if I fail?” Then he told her that she would become a famous literary figure, to which she responded similarly with: “what if I fail?”

They both laughed.

In an introduction to Mourid’s first poetry collection, Egyptian writer Latifa Al-Zayyat wrote:

“إننا قرأنا في الشعر القديم قصائد غزل، لكننا لم نقرأ قصائد حب”

(We’ve read flirtatious poems in the poetry of old, but we’ve never read poems on love.)

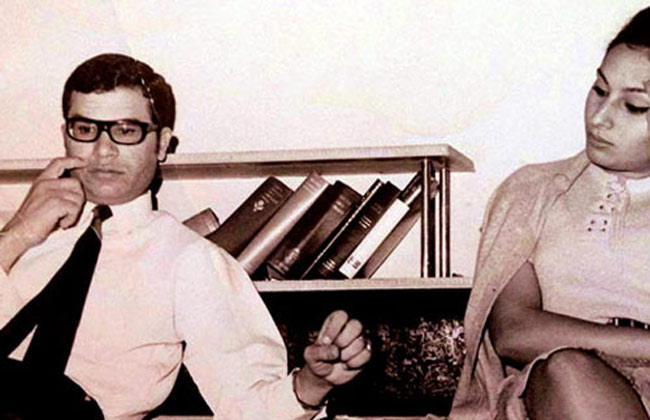

Mourid soon found his way back to Cairo, where his friendship with Radwa solidified itself as more than just that…which is also when trouble began. When Mourid requested a meeting with Radwa’s parents, they refused. He, the Palestinian refugee with no home and an unclear future, could not possibly be what Radwa’s parents wanted for her. Mourid wrote about their refusal.

As did Tamim, their son:

أمي وأبويا التقوا والحرّ للحُرَّة

شاعر من الضفة برغوثي وإسمه مريد

قالولها ده أجنبي، ما يجوزش بالمرَّة

قالت لهم يا العبيد اللي ملوكها عبيد

من إمتى كانت رام الله من بلاد برَّة

يا ناس يا أهل البلد شارياه وشاريني

من يعترض ع المحبة لما ربي يريد

(My mother and father met and the free man belongs to the free woman

A poet from the West Bank, Barghouti, and his name is Mourid

They told her he’s a foreigner, it cannot be

She told them: O slaves whose kings are slaves

Since when was Ramallah a foreign city

O people, my village’s people, I want him and he wants me

Who opposes our love when the Lord has agreed?)

When Radwa’s father, Mustafa Ashour, met Mourid, he realized that he could not stand in the way of their love. He found it so intense and profound, that he allowed it to happen. And so, Mourid and Radwa were married in July of 1970. Mourid wrote a line then, that sums up his life with Radwa:

“في ظهيرة يوم 22 يوليو عام 1970 أصبحنا عائلة، وضحكتها صارت بيتي”

(On the morning of 22 July of 1970 we became a family, and her laugh became my home.)

Mourid realized that he will never have a permanent home, but who said home had to be a country or a city when home could be a person whose love made you feel like you belonged?

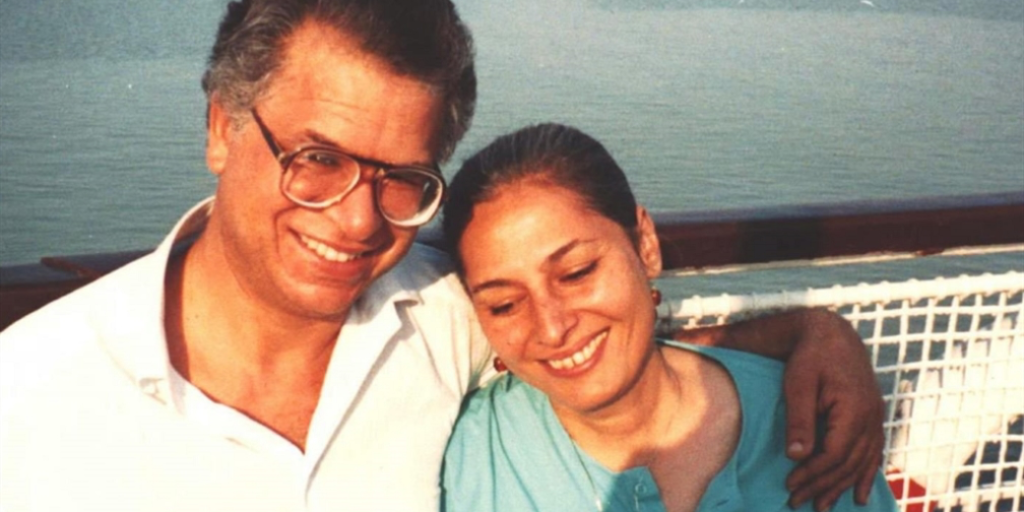

العروس رضوى عاشور ومريد البرغوثي الشهور الاولى لزواجنا ونحن هنا برفقة والدتي وشقيقي علاء في زيارة لبنان. اليوم الان هو الذكرى ال ٤٨ لزواجنا ٢٢ / ٧ pic.twitter.com/OrcIyaungv

— مريد البرغوثي (@MouridBarghouti) July 22, 2018

In 1977, Tamim Al-Barghouti was born in Cairo, the only heir to the Barghouti-Ashour legacy. Before Tamim’s first birthday, the Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel took place at the hands of Egyptian President Anwar Al-Sadat. Mourid, like many Palestinians in Egypt, refused to entertain the notion of this treaty and spoke out against it. In response, Sadat ordered the exile of every prominent Palestinian in Egypt and banned many others from entering.

Mourid and Radwa spent 17 years apart. Radwa mostly in Cairo and Mourid between cities, Beirut, Baghdad, and Budapest are where he spent the longest intervals. A lone man, wandering the world, banned from his homeland, Palestine, and from being with the woman whom he claimed to be his home. In those 17 years, they would meet up for short intervals in cities all over the world, when they could.

In 1996, the Oslo Treaty allowed for Mourid to go back to his homeland for a visit. 30 years estranged, Mourid’s visit to Ramallah produced one of his most notable works, “I Saw Ramallah”. By that time, Radwa had received her PhD and was teaching English Literature at Ain Shams University.

Three years later, in 1999, Mourid was finally allowed back in Egypt, to be reunited indefinitely with Radwa and Tamim. Tamim, who was rising to fame for his eloquence and his skillful poetry, of which he wrote in colloquial Palestinian, colloquial Egyptian, and fos’ha (standard) Arabic. Tamim writes about his mother beautifully in his poem قالولي بتحب مصر؟ قلت مش عارف (They Asked Me if I Loved Egypt? I Said I Did Not Know).

Mourid and Radwa’s struggles were not just centered around exile, war, and loss. There was also Radwa’s battle with cancer, an ongoing fight with a brain tumor that kept threatening to take her away, until it did in 2014. Mourid mourned the loss of his wife, and followed her four years later, but not before writing:

“تركتنا لا لنبكي بعدها، بل لننتصر. تركتكم بعدها لا لتبكوا بل لتنتصروا”

(She left us not to cry after her loss, but to become victorious. I leave you after her not for you to cry, but to become victorious.)

All that remains of the small family is Tamim, shouldering the legacy on his own.

Or so it seems.

In an article for Raseef22, writer Abdelrahman El-Gendy writes:

“How many times have their words saved me and other prisoners? How many times in the heart of darkness did they touch our broken hearts tenderly? How many times amidst the humiliation of powerlessness and oppression, did they prove the words of Ahmed Fouad Negm, “And the age of light is unable to remove a thousand walls” true?”

Radwa Ashour and Mourid Al-Barghouti’s light continues to pave a path for all those who are despairing, lost, and alone. It is so very difficult to speak to anyone who cares about Arab literature and politics and find them unloving of Mourid and Radwa.

Their love is entrenched in resistance and it teaches us many lessons in resilience. Most of all, Radwa and Mourid teach us that love is the strongest force on Earth, for where love is, so is strength, compassion, and resilience. They continue to be the companions of the downtrodden, the hopeless, the defeated, the lonely, and the oppressed from beyond the grave. Their love continues to be a guide for the despairing and the hopelessly romantic; endlessly empowering and intensely affectionate.

“غريب أن أبقى محتفظة بنفس النظرة إلى شخص ما طوال 30 عامًا، أن يمضي الزمن، وتمرّ السنوات، وتتبدل المشاهد، وتبقى صورته كما قرَّت في نفسي في لقاءاتنا الأولى.”

رضوى عاشور عن مريد البرغوثي

“It’s strange for me to look at someone the same way for 30 years. Time passes, years run by, scenes change, and his image remains as it did in my heart when we first met.”

Radwa Ashour about Mourid Al-Barghouti

Comments (0)