Wide citrus-soaked gardens, pouches of pumpkin seeds sold off by the parcel, and a lingering chirp of laughter: the Giza Zoo at its prime was a vision of nature trapped in concrete modernity – brimming with the rare and endemic, open-expanse enclosures and endangered fauna. It was one of the few green areas in Cairo, covering upwards of 80 acres, making it the largest zoological garden in the Middle East and oldest in Africa.

It was brought into being by none other than the notorious, Euro-enamored Khedive Ismail in the late 19th century. Initially part of the harem gardens, it featured a variety of exotic plants imported from India, Africa, and South America; a banyan tree planted in 1871 can still be seen in its mature glory to this day.

It seemed like a reconstruction of Eden: 20,000 individual animals, 400 species, and an array of animals never before seen to the local public. By the late 1870s, it was considered a “natural history museum” that encompassed “spacious European standards.” Its attendance was testament to its novelty: by the end of the Second World War, the zoo was considered one of the finest world-wide, with an annual 3.4 million visitors by 2007.

Today, the sanctuary is a memory – an unfortunate one.

Lodging sickly animals and untreated manure piles, the zoo has not only outstayed its welcome in certain milieus, but lost its place in the public sphere: entire areas have been cast into shutdown, smeared with unmentionables and keyed by jaded lovers Ahmed and Rana.

To those of us with a more postmodern set of ethics, zoos as a whole have overdue evictions; they are institutions that rely entirely on the maltreatment, exploitation, and peacocking of animals who have no real say in the matter. None of this is frontpage news, by any stretch of the imagination; Sea World made certain of that when it dovetailed publicity and public outrage, only to sell a whale plushie in consolation.

It’s questionable behavior to the polite, and entirely unhinged to the educated.

Putting animals in glass enclosures is an odd way of showing reverence to wildlife – an even odder way of viewing it. With nature in a state of continuous deterioration, many have shifted gears in order to preserve it – and the finest consideration to make is, surprisingly, not the shutting down of all zoos.

Rather, it is high time to repurpose them – it is time to consider compassionate conservation.

Giza Zoo is an aging, deteriorating structure that served its moment, but is in desperate need of a new identity. The Al-Sisi cabinet has waxed poetic about its 2030 vision, which sees a more sustainable, environmentally friendly Egypt in just under a decade. Though most of this has revolved around new yellow brick roads and emerald cities, it is worth examining the eco-benefits behind Cairo’s old structures.

Zookeepers Are Not Organic

Zookeepers, startlingly, are not found in nature. Zoos are manufactured and rely heavily on captive breeding programmes which offer up more bad times than good ones. From killing “surplus” offspring to mistreatment, many animal activists have admonished their existence entirely – and for good reason.

There is, however, a crossroads in ethicality here. While some are quick to argue the “welfare and liberty of animals,” conservationists remind of greater losses: biodiversity, ecosystem damage, endangerment and ecological integrity. Though all roads lead to Rome, the latter provides a more compelling lens to look through when considering the benefits of repurposing the Giza Zoo. A more intuitive approach hotpots them together; Oxford’s Journal of Environmental Science encourages a bifocal view which takes both into account simultaneously – caring about animal welfare while also taking accounting for environmental preservation.

This is compassionate conservation: finding a “morally acceptable balance between animal welfare concerns and species conservation commitments.”

It calls on individuals to consider both improving the environment while also pulling back current malpractice such as captive breeding, species control, translocation, genetic introgression, and biocontrol. Most incentives behind these practices are initiated with talk of revenue and big money.

However, the Giza Zoo does not garner enough bank-points to argue against compassionate conservation efforts.

Given the zoo’s current state, there is no economic or ethical justification to keep it as it is. No longer is the grass green, and no longer is the cash green either, given the Giza Zoo’s dismissal from the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) after an inability to pay admission fees. It seems reasonable then, to consider switching out Giza zookeepers for conservationists in order to salvage what little remains of the location and perhaps turn 80 acres worth of desolation into a true animal sanctuary.

It is also not impossible.

Many zoos internationally have achieved a promising balance between conservation efforts and animal welfare – albeit after a long road of missteps and manic animal rights movements. Still, it’s undeniable that zoos have made “serious and sustained efforts to ensure and enhance animal welfare,” contributing to species conservation in the process.

Not only does this pad Egypt’s glamorous 2030 vision, but aids in cultivating that same eco-friendly generation. Rather than kids growing up with memories of tossing peanuts at baboons and scraping the manure off their soles, it becomes a larger narrative of empathy and responsibility.

Given the once renowned status of the Giza Zoo, it’s a shame to see both its reputation and legacy take an ungraceful dive into the abyss.

An Argument of Heritage

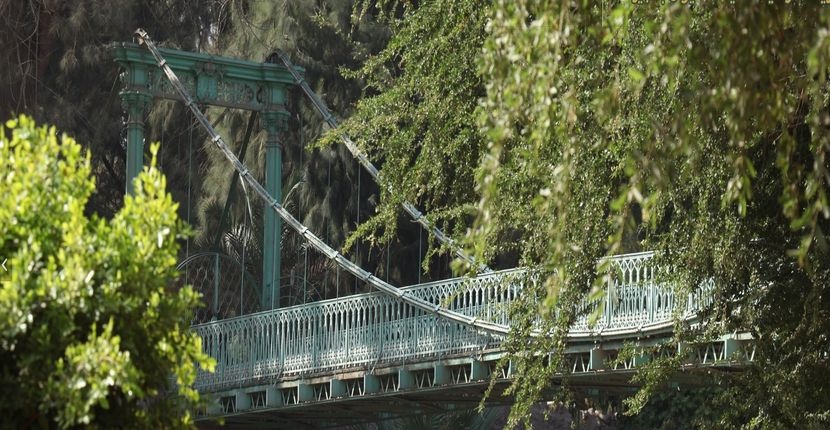

Much like any other part of Khedivial Cairo, the Giza Zoo is a monument of its time; from intricate arches to fer forge, there is a history worth considering in the structure itself. Even if conservation efforts are dismissed as flouncy and unrealistic, heritage preservation is still – and will always be – an argument worth making.

There is more left to waste here than there is gained, and no amount of waxing poetic for bygone days is doing any good. The facts are vicious and unerring: animals and architecture are mistreated, and a place that was once a haven for the lingering is now a grave-site in the making.

It’s time to revisit this location and make it a safe space for those who deserve it most: the animals inside it.

Any opinions and viewpoints expressed in this article are exclusively those of the author. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comment (1)

[…] Giza Zoo, the oldest in Africa and the MENA, has closed its doors for the first time since it opened in 1891, and is undergoing renovations. […]