A thumb brushes under his eye, and he feels only texture: the world is a fold of black and odd, viscous patches of color. His mother presses his head into her chest, her breathing rapid, in mourning; what he gathers is a simple, undeniable fact—he is blind at age two.

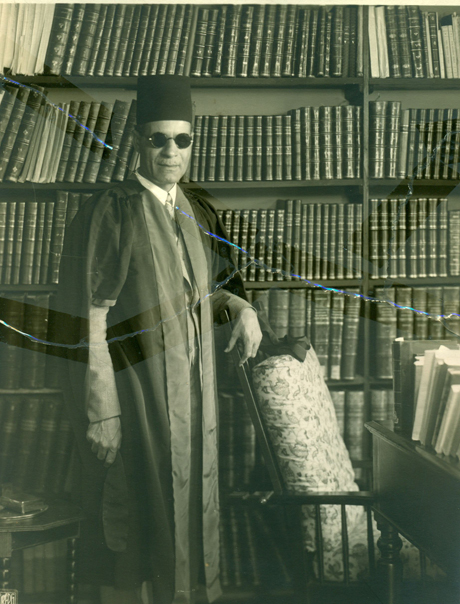

Taha Hussein was born in November 1889 into modest upbringings, under unfortunate circumstances. Through ailment and disability, he would rise to become one of Egypt’s modernist titans. As a novelist and essayist, Hussein would distinguish himself as the “Dean of Arabic Literature,” and the “the greatest single intellectual and cultural influence on the literature of his period” – a claim supported by his 21 Nobel Prize nominations.

As the seventh child in a family of 13, his handling was lacking. Accordingly, when the young Hussein fell victim to an eye infection, his superstitious, low-brow mother led to his subsequent blindness. By not affording him the necessary treatment, but rather unorthodox, oil-based remedies, she unintentionally sabotaged the young Hussein.

By 1902 he was sent to an al-Azhar seminary in Cairo, where he received a thorough Islamic education. Joining al-Kuttab, Hussein memorized the Qur’an in full, though did not find himself entirely in the conservative milieu that surrounded him.

It would not be long before his modernist rhetoric put him at odds with the traditional thought-leaders within the institution. As a result, he would leave al-Azhar in favor of the secular University of Cairo (then: Fouad I University) in 1908, and would be the first of its students to obtain a doctorate in 1914. His Ph.D. was a focused endeavor, specializing in the poetry of also-blind, controversial philosopher, Abu el-Alaa el-Ma’arri.

While his blindness presumably caused him “great torture,” it led to one of Hussein’s fondest meetings. “Sweet-voice[d]” Suzanne was a fellow student who read to him, given most literary and educational resources were unavailable in Braille. Suzanne would later become his wife, mentor, advisor, assistant, life-long love, and best friend.

It was also during his university years that Hussein started work on his now-famous Al-Ayyam (the Days, 1929), a book that detailed his life extensively.

Ambitious and knowledge-hungry, Hussein was insatiable when it came to his education; he left Egypt to obtain a second doctorate at Paris’ Sorbonne in 1917, specializing this time in social philosophy. This degree was one of many factors that came to shape Taha Hussein’s legacy as a modern thinker and a social force. In addition to his more exhaustive education, he obtained a diploma in Roman civilization before leaving the Sorbonne.

Upon his return to Egypt in 1919, he was appointed professor of history at Cairo University, where he would flourish as a visionary of the Arab cultural renaissance.

“To those burning with their yearning for justice,” wrote Hussein, “to those rendered sleepless by their fear of injustice; to those and those together, I direct these words.”

His work was a function of three: the scientific study of Arabic literature and Islamic history, creative literary pursuits aimed to combat poverty and ignorance, and finally, socio-political essays that explored the nature of the Egyptian state and its people. The latter two of which were controversial enough to cost him his post as a classics professor.

Though most famous for his legacy, his novels are essential to understanding the thought processes behind Hussein as a thinker. His stories were woven with “astounding insight and compassion,” alongside a visceral pursuit of justice and a profound understanding of Islam.

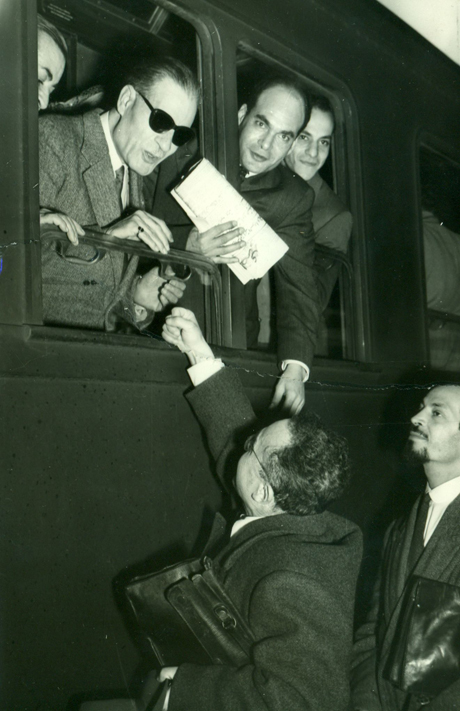

Though the road ahead was still vibrant and eventful. In 1950, he was appointed the Minister of Education, with the motto: “education is like the air we breathe and the water we drink”: essential to the human experience. It is true that millions of Egyptians today owe their literacy to the practices and scholarly ethics set in place by Taha Hussein.

His influence was all-encompassing, and it was during his meeting with the equally-famed, blind-deaf Helen Keller that his advocacy was introduced to the West.

Helen Keller wrote of visiting Hussein in Egypt in 1952:

“For years I had read about Taha Hussein Pasha, and I cannot express my delight one day when he visited me at the Semiramis Hotel, bringing his wife and son, and stayed a whole hour. I was privileged to touch his face, and how handsome, scholarly, and full of inward light it was! His responsive tenderness warmed my heart, and I felt as if I had known him always. We discussed many topics — Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Plato, and Socrates, the liberating power of philosophy, Taha Hussein’s studies of the great blind Arab philosopher of the tenth century, and his work for the blind. He told me that while he was Minister of Education, he had worked quietly enabling capable blind persons to go to universities and colleges and that he was still deeply interested in that measure. He said that one of the chief needs of blind students in Egypt was secondary schools from which they could go to finish their education in college. It was a precious boon to me to feel Taha Hussein’s personality behind me when I called on various ministers of the Government and begged them to authorize those secondary schools.”

For years to come, until his passing on October 28, 1973, Hussein would go on to write prolifically. Some of his famous books include Doaa al Karawan (The Curlew’s Prayer, 1934), Wa’d al-Haqq (The Fulfilled Promise, 1949), and naturally, Al-Ayyam. Though globally acclaimed, there have been attempts to remove Al-Ayyam from the Egyptian school curriculum, with some arguing that it does little but aggravate conventionalists and tarnish the image of local religious authority, al-Azhar.

Still, this has not stopped Hussein from being celebrated throughout the years, being the second Arabic writer officially considered for a Nobel prize, outside of Naguib Mahfouz.

Comments (5)

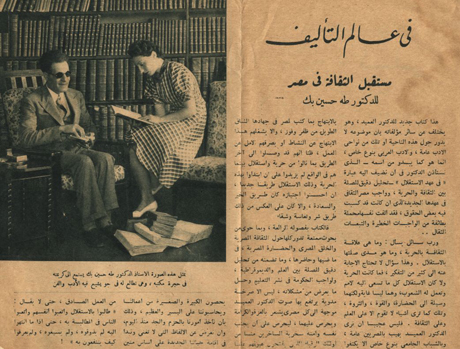

[…] مقابل طه حسينالعميد الكفيف للأدب العربي شابة طموحة وقوية الرأس. تزن […]

[…] across from Taha Hussien, the Blind Dean of Arabic Literature, is an ambitious, headstrong young woman. She weighs down […]