What if all the writings on the walls of the temples, tombs and papyrus were just one side of the story, like the propaganda of our time?” whispered my friend in what was supposed to be the end of a long discussion about the current situation in Egypt.

We both laughed as we struggled to analyze the recent chain of events that had paved the way to this situation in 2015. Our appetite to start another debate was shrinking these days – not because we became intolerant of different views, as the mainstream in Egypt has, but we had lost our appetite out of futility! In fact, we were mentally and emotionally exhausted, as has been the case for many young Egyptians over the past four years – a time that started with high hopes and ended in despair.

So we let it go, until one day when I was watching a documentary about The Ramesseum, the great temple of Pharaoh Ramesses II. In this magnificent temple, a huge sidewall glorified Ramesses’ victory over the Hittites in the battle of Kadesh, despite the conclusion most historians had reached, which was that the outcome of this battle was either a draw or a military defeat for the army of Ramesses. At this point, my friend’s question came to mind.

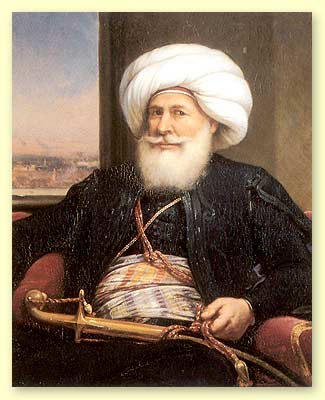

Not long after this, I was reading an article in which I found out that King Fuad of Egypt formed a committee under Hassan Nashat Pasha – who was serving as acting chief of the royal court – to gather all official documents since Muhammed Ali. The King then asked foreign historians to re-write the history of the royal family in a way that polished Muhammad Ali family’s image. As I became more concerned, I started to dig deeper.

I soon read through the fourth volume of the most comprehensive reference for that time, Amazing Testimonies of Lives and Events (“Ajiab Al-Athar fi Al-Tarajim wa Al- Akhbar”). In this book, Abdel-Rahman al-Jabarti tells another side of the story of Egypt under the Pasha. In reality, in the age of the Renaissance, the Egyptians suffered injustice, suppression, slavery and ignorance. Al-Jabarti’s book was banned until Khedive Tawfiq approved publishing the book in 1880. Professor Khaled Fahmy took another step in the same direction by working on the Ottoman’s archives, using original Turkish texts as well as Arabic translation in the Egyptian National Archives.

In his marvellous book All the Pasha’s Men: Mohamed Ali Pasha, His Army and the Founding of Modern Egypt, Khaled Fahmy demonstrates several arguments which refute the traditional thesis of “The Founder of Modern Egyptian History”. For example, he reveals significant differences between the original Turkish documents and their Arabic translation. He explains that in many cases, some parts of the original texts were omitted in the translation in order not to upset long-established image of the Pasha. Fahmy also reviewed several books of early historians, and concluded they were offered selected documents, mostly taken out of historical context, to serve the same purpose.

Fahmy also highlights an article by the famous Islamic modernist scholar Muhammad Abduh in which he “described Muhammad Ali as a destroyer rather than founder”. The pioneer thinker clearly questioned the intentions of the Pasha, as he argued that all what we may call reforms were only meant to support the Pasha’s position in Egypt. For example, according to Abduh, whilst Muhammad Ali sent numerous student missions to Europe to study medicine, they were not empowered to cure the thousands of Egyptians who were in desperate need for medical care. In other words, he argued that Muhammad Ali’s so called modernization of Egypt had left the majority of the people in Egypt worse off.

Who Writes Egypt’s Modern History?

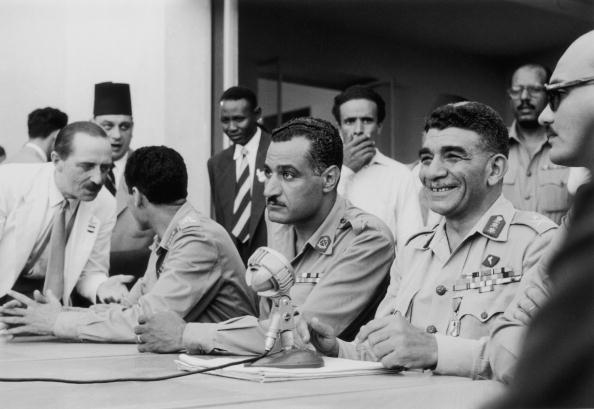

King Fuad’s idea of reshaping history in this way was so appealing that President Gamal Abdel Nasser and President Anwar el-Sadat formed similar committees to “rewrite” the history of Egypt. However the work of these committees was largely unknown.

Before the 1952 revolution/coup, Ahmed Urabi’s uprising of 1882 was called an “insurrection”. History books told us that members of Mustafa Kamel’s National Party, among others in Egypt, treated Urabi as a traitor and held him responsible for the British occupation of Egypt. After 1952, this was reversed. Urabi was represented as a national hero, whose “revolution” backfired due to a conspiracy by the British and the royal palace. The picture of Urabi Pasha -denoting the army- on his white horse safeguarding the demands of the Egyptian people replaced the old tale of treason. Considerable criticism of Urabi’s judgments and decisions was sidelined, even if it was the work of respectful intellectuals like Abd al-Rahman al-Rafai. Denouncing a historical leader would have grave consequences on the leadership of that time.

This continued throughout the century. A reporter once toured downtown Cairo asking: “Who was the first president of the Arab Republic of Egypt?” The majority replied: “Nasser”, while only few remembered that it was in fact Muhammad Naguib. This was not a coincidence.

In 1954, the Revolution Command Council announced Naguib’s resignation, which happened due to a disagreement between him and Nasser. Naguib was placed under house arrest and his role in the revolution/coup was eliminated. This remained the case until 1972 when President Sadat put an end to his house arrest. President Mubarak attended his funeral, and in 2013 the Order of the Nile was awarded to his name by interim-president Adly Mansour.

A similarly remarkable incident was when President Sadat ignored four of his top generals – the Chief of Staff Saad el-din el Shazly, the commander of the third Egyptian Army Abd el-Munim Wassel and the commanders of the second Egyptian Army Saad Mamoun and Abd el-Munim Khalil – during the 1973 victory celebration ceremony, which took place in the Egyptian parliament. Bypassing these men covered up the series of Sadat’s fatal decisions that had led to a failed eastward advance, followed by a successful Israeli counter attack crossing the canal and trapping the third Egyptian army. In the diaries of Saad el din el Shazly, he recalled a conversation with Saad Mamoun prior to the war: Mamoun told him if the troops failed to cross the Suez Canal, they will take all the blame. Ironically, the troops succeeded yet the four men were punished for an ordinary professional disagreement, regardless that they were proven right. President Sadat wanted a total victory, and so it was!

For Saad el-Din el-Shazly, the worst was yet to come. After Hosni Mubarak, who served as commander of the Egyptian air force during the war, became president, the story of the victory changed once again to glorify the role of the air forces above the rest. In the memorial of 6th October’s war, a big portrait was set, in which Mubarak replaced Saad el-Din el-Shazly, as if the man never existed. Again, after 25th of January revolution, the name of Saad el-din el-Shazly was awarded the Order of the Nile. But the damage had already been done.

A few years ago, Ahmed el-Moslemany – an Egyptian journalist – advocated in a series of articles the need for reevaluating the historiography in Egypt. Many intellectuals and historians were encouraged to do so, but an idea such as this, which sits outside traditional nationalistic clichés, faced fierce opposition. Truth be told, all regimes in Egypt have been giving much more attention to their own persistence, even if the awareness of many generations was at stake.

It is clear where the consequences of several attempts of “rewriting” the history of Egypt has led us. Even “reevaluating” the history won’t make enough relevant change. Writing history is not about taking sides. Historiography is an inclusive process that aims to understand the lessons of the past. In the words of E. H. Carr — history is an unending dialogue between the past and the present. Tackling the history of Egypt in a way that considers different perspectives of events won’t just highlight the fundamentals of the malfunctioning stage we are going through, but will give us some room for free debates that could enlighten our way toward a better future.

Comments (10)

Egypt’s histroy will only be written by the well and truly people of the country. All this line of rulers from Nasser to Gen Sisi have all contributed to the worsening of Egypt and its people rather than any thing else. Mohamed Naguib was a true and a sincere ruler thats why he we removed, put under house arrest till the day he died. Same happened to Dr M. Morsi who was not given a breathing space and was removed in few moths time. Zion&bors are in total control of the country and this won’t take a long time. IMO ,the coup leaders will soon be removed giving way either to fresh new elections or the return of the first democraticaly elected Morsi and his cabinet.

There’s nothing as pathetic as a looser a.k.a. Muslim Brother! If Morsi were “democratically” elected … then one should immediately abolish democracy as this kind of “democracy” is known in honest parts of the world as election rigging and fraud.

Minitrue and doublethink. The populace bellyfeel and the media duckspeak.