By Tanya El Kashef

In July 2015, I took part in a sailing voyage from Athens to Hurghada with the purpose of delivering four sailboats to Egypt. A daring journey for a group made up of mostly novices, it took nineteen days of sailing through six Greek islands, the wrath of Meltemi winds, long late night sails and the Suez Canal; in the end, we slowly but surely made our way home to the Red Sea.

The idea was to spend my summer vacation doing something that would add value and experience, so when the opportunity to deliver four sailboats from Greece with Red Sea Sails came my way, I didn’t hesitate to take it on.

A budding project, Red Sea Sails intends to establish a sailing school, to provide sailboat charters and ultimately spark a sailing culture in a sea it believes is an ideal setting. While sailing is very new to the Red Sea – which currently have about ten sailboats in El Gouna and Hurghada combined – it is not an entirely new sport to Egypt and has had its popularity in places like Cairo, Alexandria and Ismailia. And although the days of elegant yacht clubs and their community of sailors are long gone, it is not uncommon to hear friends say that they have dabbled in the sport or that they used to go sailing with their grandfathers.

The feedback I received prior to the trip was a mix of nostalgic memories, intrigue and enthusiasm, and these sorts of reactions affirmed that an interest in sailing did exist and could possibly be fostered. However, it takes more than mere interest to become a well-rounded sailor – a fact I was soon to discover.

Nineteen Days on a Sailboat

With a plan to cover roughly three weeks of sailing, the fleet left Glyfada and headed southeast towards Hurghada, with plans to stop at different locations along the way. By allocating a certified instructor to each of the four boats, the trip provided a learning experience for the novices on board. With an average of five people per boat, everyone was considered a crew member and was responsible for all sorts of tasks from sailing the boat to keeping it clean, comfortable and most importantly, safe.

Safety is the first thing they will teach you on a sailing course, but the first lesson I truly learned was patience. Perhaps sailing across a sea from continent to continent is extreme compared to taking a course for a few days, sticking to the islands of Greece or along the coast of Spain; but if you want to be a sailor, it takes more than a few days at sea, and requires hours of traveling to gain the experience – and hours of traveling is exactly what a sailboat will offer.

In regards to patience, sailboats are very slow. The fastest recorded sailing speed is 44.1 knots – which converts to about 81.5 kilometers per hour on land – and was achieved by a professional racing team from New Zealand. In general, the speed of sailboats can range from four knots up to thirteen knots; so even the largest and fastest of boats rarely go above 25 kilometers per hour. However, this leisurely pace is part of sailing’s charm and should not be written off as something bad. Sailing is not about hurrying; it’s meditative and calls for tuning into nature, your environment, as well as to yourself.

That said, it’s a delightful thing to learn something new as an adult, and I found removing myself from my comfort zones and repetitive habits to be an illuminating and rewarding experience. In just under three weeks, we transformed from awkward bodies moving clumsily on a boat to people that understood what line affects which sail and were casually saying things like ‘on the starboard side’ and ‘what’s our bearing?’

It didn’t take long to adapt to the swing of the boat, which is constant and sometimes quite severe; the size of the cabins that seemed questionable at the marina suddenly expanded and seemed like ample space to lay and rest in once we were at sea. For someone not used to being at sea, the noticeable creaks and swooshes soon became the most ordinary of sounds; you begin to find a rhythm in life on a boat – assuming of course that you don’t get seasick, in which case, ginger or motion sickness medicine will keep the situation under control.

Although having the physical strength to pull lines and run around on deck was one of my initial concerns, it became apparent quite quickly that the trial of living at sea would largely be internal. Even the closest of friends or couples will begin to get cabin fever after hours of traveling together in a limited space, and egos will sooner or later want to confront each other. But the beauty of being out at sea is that there is no space for egos, as the sea has a humbling effect.

Life-Jackets On!

There’s an Arabic proverb that says: “The sea is perfidious” – naturally this sounds more profound in Arabic (el bahr ghaddar). It was first told to me as our boat thrashed from side to side in 47 knot gusts of wind, flinging people and belongings in all directions; when the sound of crashing glass came with every wave that swerved, and after being told to put on my life jacket, something about the saying rang a little extra true.

We hit the Meltemi winds in the Aegean Sea as we left Amorgos heading to Astypalaia. This was the third island we visited after Kithnos and Paros, and about our seventh day at sea. Considering that the katabatic winds -which are basically winds that flow downhill, carried by the force of gravity- were averaging 35 knots with gusts of the aforementioned 47 knots every 10 minutes, it took a lot of mental stamina to overcome the unfamiliarity – and fear – of being on a dramatically swaying boat in the middle of the sea; of seeing three-meter waves gain momentum behind us as we stared in horror and bewilderment. After enduring this weather for about eight hours, we finally reached Astypalaia’s marina with a boat covered in water and exhaustion, and for a moment there I thought I would never be able to get back on.

Crossing the Mediterranean: Welcome to Egypt

Following a couple of days of rest and recuperation in Astypalaia, and after an overnight stay in a bay at Simi, the fleet made its way to Rhodes for the final stop in Greece before crossing to Egypt. Shopping for a 70-hour journey was nothing less than apocalyptic with each boat piling in four carts worth of food and water; the fact that Greece was in the midst of an economic crisis didn’t help with the end-of-the world feeling either. Anxious about the long way ahead, we left port at sunset and began the two and a half day downwind sail to Egypt. With calm rather than playful weather, the time passed as smoothly as anyone could have hoped; a couple of tuna sashimi breakfasts, three endless night shifts, a lot of walkie-talkie communication and a few meltdowns later, the fleet arrived to Egypt safe and sound.

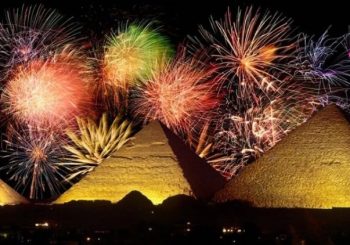

Despite Port Said earning the nickname ‘Port Sewage’ because of its blinding smell, the arrival to Egypt was a happy one; we had officially crossed the Mediterranean. After a few hours of champagne popping, loud singing, paper work and an authentic kofta and kabab lunch at the dilapidated Yacht Club, we were able to depart at four in the morning towards the Suez Canal.

Pilots are assigned to every boat that enters Port Said and remain until Port Suez – after crossing the canal – for security reasons. Though we’d heard several stories of how painful this portion of the trip could be in regards to waiting time and having a stranger on board, our path was paved with wonderful luck and we were able to reach the Red Sea in just a day.

The two different pilots for the two portions of the trip were also a pleasant surprise. Bearing scrapbooks filled with every one of his trips, El Rayes Said – AKA Speedy Said – escorted us from the mid-point at Ismailia until Suez. Based in Ismailia for the past 20 years, Said has met countless sailors from all over the world, and he treasures little mementos from each of them. According to him, about 10-15 sailboats make the crossing each year

The crossing of the Suez Canal can be best described as quiet and uneventful. Compared to the vast and vibrant sea, the canal is narrow and the surrounding colors are pale and muted. Apart from the occasional container ship passing us at four times our speed, not much activity was detected. Since sailboats are forbidden to sail through the canal, we had to motor the whole 190 kilometers at a speed of six knots, which only added to the languidness of the journey.

By sunset, we reached Port Suez, which, like most other ports in Egypt, is run-down and leaves much to desire. Saying goodbye to Speedy Said and excited to be in such close proximity to the Red Sea, we started off for Ras Sedr the next morning.

Sailing the Red Sea

This might have been one of the first times a fleet of four sailboats traveled the Red Sea together, and in that sense, we were literally making history. Different in its wind patterns, waves and with tricky-to-maneuver reefs, the Red Sea is still largely undiscovered from a sailing perspective. However, the Red Sea is dynamic and active, offering a lot in terms of destinations and water sports.

After spending an afternoon at one of Ras Sedr’s local camps – and the night moored out at sea – we then headed to Gysum in the Strait of Gobal, where a secluded bay gave us some privacy as well as a heavenly pool of water to wake up to. Locations like these and the Dolphin House – which was the final stop before we reached the Hurghada marina – along with Tawila, Magaweesh and many others, are just some popular spots for diving and kite-surfing. The recent introduction of sailing here has contributed to the Red Sea’s growing network of water sports.

What about sailing in the Mediterranean, you might wonder? While the North Coast is certainly easier to reach from Europe than the Red Sea, the North Coast’s development remains far more rigid and regressive than that of its sister sea – though hopefully this is in the process of changing.

Several factors add to the lack of a sailing and boating community on the North Coast, the first of which are security measures and restrictions that have been in place since the days of Nasser. Apart from projects such as Marassi and Almaza Bay – which are still under development – the absence of sufficient marinas, Yacht Clubs and attention to touristic value only furthers the problem.

While the Red Sea enjoys more activity and ultimately sees more visitors throughout the year, that is not to say that it doesn’t come without its own rules and regulations. All boats need to get permission from the Coast Guard 24 hours before planning to stay the night out, while Egyptian boats need to get the same type of permission to leave for a daily trip. Boats registered abroad are at an advantage, since they can obtain permission for a daily trip on the spot, but they are still required to return by sunset.

Interestingly enough, out of several Canadians and UK citizens, an American, a Lebanese and an Italian, Egyptians are the only ones required to have their fingerprints taken before exiting Europe from the Rhodes marina. Egyptians are also required to get a cruising permit from the Egyptian authorities once we reached Port Said – a restriction that did not apply to foreign guests.

However, the rewards of being out on the Red Sea far outshine any minor legality required to reach it. From El Gouna all the way down to Sudan, and across to Dahab and Ras Mohammed, a playground of islands and reefs surely awaits anyone bold enough to partake in it.

Comments (9)

[…] From Greece to Egypt on a Sailboat: Reviving Egypt’s Sailing Culture – While sailing is very new to the Red Sea – with currently have about ten sailboats in El Gouna and Hurghada combined – it … offering a lot in terms of destinations and water sports. After spending an afternoon at one … […]

[…] From Greece to Egypt on a Sailboat: Reviving Egypt’s Sailing Culture – A budding project, Red Sea Sails intends to establish a sailing school, to provide sailboat charters … combined – it is not an entirely new sport to Egypt and has had its popularity in places like Cairo, Alexandria and … […]