The Sufi is the traveler in the way of Love. This is how Khaled Muhammad Abduh defines the Sufi in his most recent book, On the Meaning of Being a Sufi. The book is a collection of essays that vary between narratives, personal experiences, academic insights and glimpses of the lives of great Muslim spiritual figures who deeply affected his life.

One such figure is the Persian mystic and Sufi master Al-Husayn ibn-Mansur al-Hallaj (c.858- 922AD/244-309AH). Since his introduction to the life and writings of Al-Hallaj during school years, Abduh became a wayfarer in his path.

In the introduction of his book On the Meaning of Being a Sufi, Abduh describes how Sufism was drawn into his life. His interest in the field of comparative religions made him immerse himself in extensive readings in the Sufi literature. After a while, he came to the realization: “I understood that Love cannot be taught. It cannot be sought in books.” He decided that the spiritual experience of the Sufi masters had to be felt; it had to be lived. This explained to him why so many meanings in Sufi texts are hard to grasp. “The inability to understand is in itself a realization,” a close friend consoled him when was faced with the difficulty of interpreting the full meaning of Al-Hallaj’s words.

Born in southern Iran, Al-Hallaj received a spiritual education from the great mystic Sahl al-Tustari. At a certain point, he distanced himself from the teachings of his Shaykh, embarking on his own spiritual journey. Seen as highly controversial, Al-Hallaj angered the orthodox theologians of his time, who disapproved of his mystical experiences as recorded in his writings and poetry. He was arrested on charges of heresy, imprisoned, tortured and finally crucified. The life and death of Al-Hallaj have stirred great debate and great emotion, but most importantly they have created of him an icon of the dervish sparing his own life for the love of the Divine.

Khaled Muhammad Abduh is known in the social media circles as Khaled Al-Hallaj. To his followers, he symbolizes a quest for learning and a world of enlightened spirituality.

Abduh launched an online site for Islamic and Sufism studies known as Tawaseen after the name of one of Al-Hallaj’s most famous as well as most controversial books.

The site aims at creating a platform for the Arab reader to have access to the aesthetic and spiritual aspects of Islam. By providing full attention to Sufism studies, Tawaseen hopes to renew the interest in serious scholarship on Sufism, as well as to redress the misconceptions about Sufism. Abduh says, “Tawaseen is not promoting any Sufi order or Tariqah. Indeed, it is the Sufi orders that almost killed the spiritual aspect of Sufism by caging it within a system of thought and behavior that has to conform to the hierarchy of its institutional leadership.”

Abduh graduated from Dar al-Ulum, obtaining both his B.A. and M.A. He is currently working on his Ph.D. from the Department of Philosophy in the Faculty of Art in Cairo University.

Like Al-Hallaj, Khaled Muhammad Abduh received guidance in the Bektashyah order, named after the 13th century Haji Bektash Veli from Khorasan. After a while, Abduh decided to embark on his own spiritual journey. He later developed a critical view of Sufi orders, calling for reforms and for what he describes as post-tariqah Sufism, i.e. a Sufism that goes beyond dogmatism and delves deeper into the spiritual aspects of Islam.

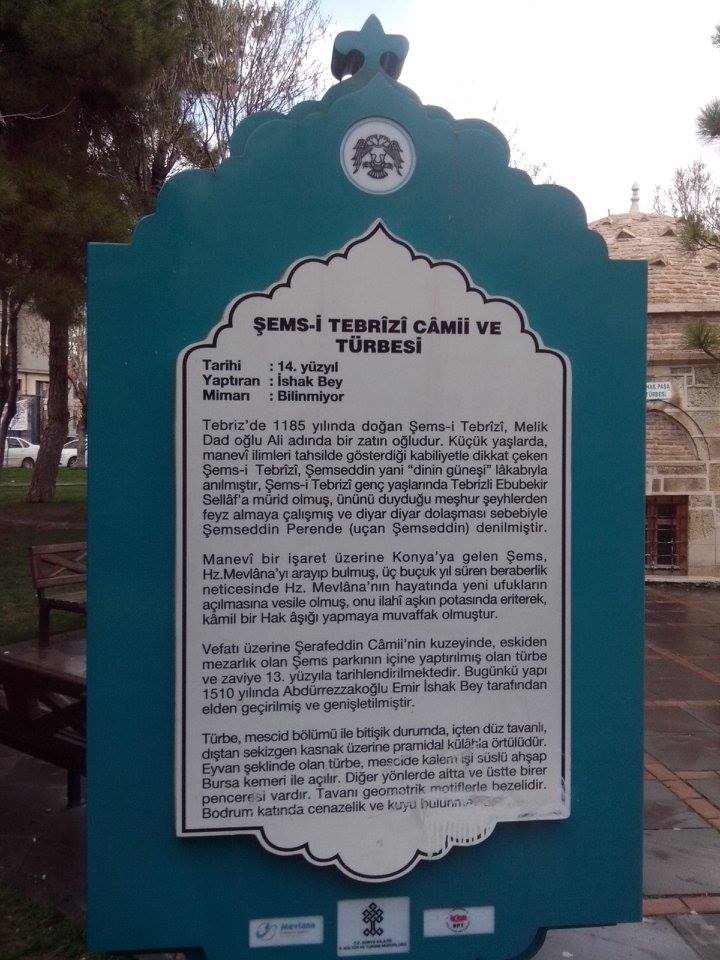

It is the latter point that made him find refuge in the world of Jalaluldin al-Rumi. He says: “Mevlana’s company enchants me. Sometimes I look at his name and smile. I think about how at a certain time he made me reunite with myself, and made me gaze at something beautiful that I will never forget.” He observes that Al-Rumi had all the training he could get due to the religious status of his father; however, it was only the encounter with his mentor, Shams Tabriz, that made him blossom spiritually.

Abduh also co-authored a book entitled Al-Rumi Between the Orient and the Occident.

Despite his academic training, Abduh is a wayfarer par excellence. Talking to him will take you to two irreconcilable worlds: Analytical criticism on the one hand, and ecstatic mysticism on the other. His sharp words reveal the quality of a solid researcher who takes nothing at face value. Yet, he does not hide an anxiety that is symptomatic of those yearning for internal fulfilment; a search for what is beyond external knowledge; a higher Truth.

He may seem to be someone who wears many hats: The researcher, the seeker, the murid or spiritual student, and the existentialist. He is indeed the summation of all the hats he wears, and he conveys the energy as well as the tension resulting therewith.

He says: “The path is not a distance to cross in order to reach it. Our steps do not get us any nearer. Perhaps, the search is the path; perhaps the pain, the wonderment, the joy; perhaps the sum of it all. All what I know is that there is no path for an ever-renewed being that is paved for him/her by others.”

Abduh’s book On the Meaning of Being a Sufi is highly important at a time witnessing an increased interest in the Sufi symbols. He sees this phenomenon as a consequence of the tearing down of the authority figures of religion as well as the disillusionment Egypt had with its short experience of Islamist rule.

Such disillusionment created what he calls a segment of Egyptians that seeks an Islam-lite and that, by misperception, thinks they can find in Sufism. The Islam-lite fans are attracted to the dancing dervishes, to the festivities of mulids and inshad concerts. They recite lines by Al-Rumi and Al-Hallaj and feel their energy, but they do not go any deeper.

On the increased mania in Egypt about the dervish as an icon of the Sufi path, Abduh thinks that the attraction to the superficial aspects of Sufism has done injustice to the dervish. “In my observations and life experience, I witnessed the dervish as the real flesh of Sufism. He is not a symbol. He is this person in humble disguise giving out from his soul to assist others. The dervish has only one destination: Allah,” he explains.

The significance of the book On the Meaning of Being a Sufi is that it sets the tone for a true understanding of what Sufism is, away from the superficial attraction to its symbols. It starts from a realistic understanding of where Egyptian youth stand, and why they are in an almost state of disbelief. Disbelief in authority; disbelief in a faith not genuinely internalized. He says: “The Sufi searches for a heart that beats with life; he requests to be guided to ascension every moment in which he can renew his connection with God.”

Abduh will discuss On the Meaning of Being a Sufi in a book-signing event on March 22 at 7 p.m. in Al-Balad Bookshop.

Comments (0)